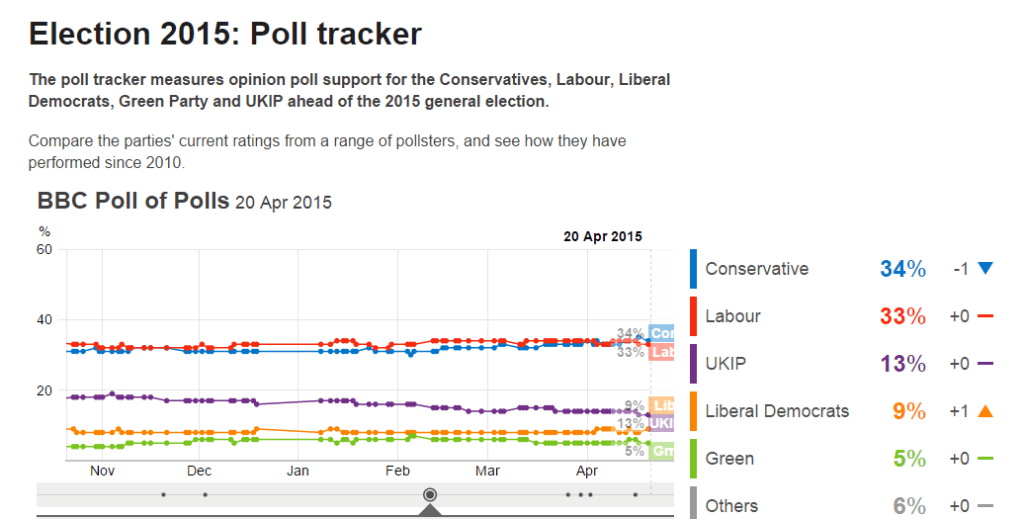

To make sense of the opinion polls in Britain’s general election it is best to look at the BBC poll of polls.

There just isn’t much going on. When each poll comes out there is a breathless headline, as the votes seem to shift from the last time the poll was taken – and this is usually expressed in terms of the gap between the top two parties. For example yesterday the Ashcroft poll showed a 4% Conservative lead rising from zero the previous time; and ICM showed the Conservative lead dropping by 2% to 2%. But all that is happening is random variation around something quite stable: Conservatives and Labour both on 34%; Ukip on 14%; the Lib Dems on 8%; and the Greens on 5%. Perhaps the Conservatives and Lib Dems have edged up slightly at the expense of Labour and Ukip in the last few days – but it is too early to tell. The big picture is remarkable stability.

The Conservatives seem to be the most perplexed by this. The party had a plan, the best possible professional advice, carefully tested on samples of voters, and everything had been working well. Good economic statistics have been coming out each week; they easily outmanoeuvred Labour in the Budget; the press mobilised and they have plenty of money. But they are stuck.

Their plan was to scare voters with the prospect of a Labour victory, both by demonising Labour’s leader Ed Miliband, and raising the prospect of higher tax or borrowing under Labour. Against the minor parties luring voters away, they created the phrase “coalition of chaos” to tap into general scepticism that coalitions mean broken promises. With this, they had clearly calculated, they could bring in an election winning score, with the upper 30s in poll ratings and a lead over Labour of 6% or more. This was more about hauling voters in from Ukip and the Lib Dems, and abstainers, than actually converting Labour voters from 2010.

But the Tory approach to this election has proved to be all tactics and no strategy. Those professional advisers call themselves “strategists”, but they their brains carry no strategic thoughts. This is how the modern political class thinks: and so they are blaming failure on poor tactics. Much has been made of Mr Miliband doing well on television and so exceeding the low expectations. There is some evidence for this (his ratings seem to be a bit less dismal). But his performances cringe-worthy as ever – full of abstract ideas and only token connection with real people. The real problem is that the Tories are fighting against two very damaged brands. First their own, as the “nasty party”, on the side of the rich. Second the general brand of mainstream politicians as slippery so-and-sos out for themselves. And their problem is that strategically the party has gone backwards in the last five years. No clever tactics can cover for that.

Things had been picking up for the Conservatives when David Cameron took over in 2005. He worked hard to detoxify the Tory brand by associating it with softer policies and softer images. This had been working very well until shaken by the twin shocks of economic crisis and the MPs expenses scandal. Still, going into coalition with the Liberal Democrats in 2010 was an excellent strategic move. It gave substance to the detoxification process. But thereafter it collapsed. It turned out that detoxification was a tactic for the 2010 election, not a strategy. Out came all the vile Tory instincts: obsessive anti-Europeanism; bashing the disadvantaged; scepticism of environmental policies; and so on. This was mainly driven by the party’s backbenchers – but Mr Cameron lifted not a finger to stop it. A low point came in 2011 with the party’s campaign against implementing the Alternative Vote (AV) electoral system, when they not only deployed a series of spurious arguments, but they launched a particularly nasty attack on the Lib Dem leader, Nick Clegg. Funnily enough, supporting AV would have been a good strategic move for the Tories – as this system tends to reinforce two party politics; advantages to the Lib Dems would have been short-lived. Since then the Tories have compounded their strategic errors – notably by neglecting Scotland and stirring up English suspicions of the Scottish. I will allow Mr Cameron credit for two positive strategic moves: support for gay marriage (which has helped detoxify the brand amongst gays, in spite of interanl opposition within the party) and the renegotiate-and-referendum policy on Europe. The latter is often viewed as a tactical concession to Ukip pressure – but there is real strategic value for the Conservatives in it – though a referendum campaign could kill the party, it is often strategically necessary to embrace risk.

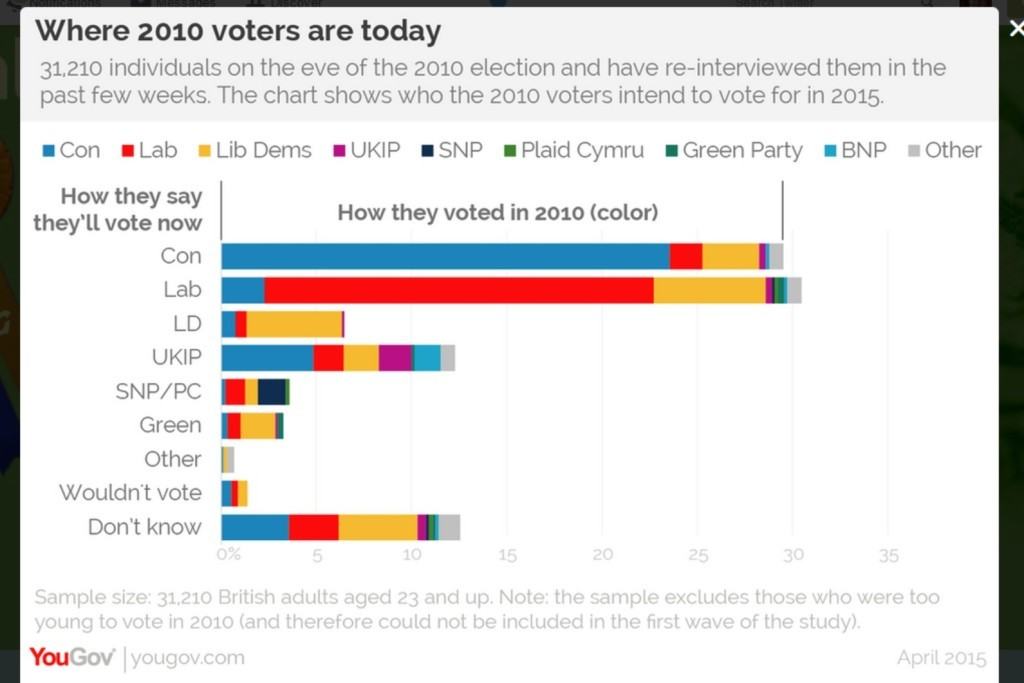

Labour are no better. Their “strategists” conjured up a cunning tactical plan to win them the 2015 election: the 35% strategy. The idea was not so much compete to for the Conservative vote, but to hang on to their core vote and scoop up a large chunk of the ex-Lib Dem vote. This equates roughly to 35%, and would ordinarily be enough to win under the country’s electoral system, if the Tories remain undermined by Ukip. This fantastic graphic from YouGov shows that this has largely been working (hat-tip Mike Smithson of Political Betting, on of the best places to go for objective news on polling).

Labour have been boosted by a large slug of ex-Lib Dem votes (though the Greens have scooped up a lot of these too – I suspect this is mainly in safe Labour seats). Meanwhile a large slug of the Tory vote has gone to Ukip.

Labour have been boosted by a large slug of ex-Lib Dem votes (though the Greens have scooped up a lot of these too – I suspect this is mainly in safe Labour seats). Meanwhile a large slug of the Tory vote has gone to Ukip.

Of course there’s a major flaw in Labour’s plan. Scotland. Labour’s relentless focus on political tactics rather than strategy meant that they didn’t see the SNP juggernaut approaching, in spite of its clear visibility ever since the Scottish assembly elections of 2011. It looks likely that the SNP will sweep Labour out of Scotland, along with the Lib Dems. Labour weren’t ready for this, and have had no effective tactics for handling it. They wasted a lot of energy on trying to tell their voters that a vote for the SNP would let the Tories in. The SNP have had little trouble in torpedoing this notion.

And this is the sort of thing that happens if you systematically neglect strategy, and focus on short-term advantage. You are vulnerable not just to getting stuck in a rut, like the Tories, but to sudden collapses in support. Look at the Lib Dems. The party had been relentlessly tactical in building its support base, especially under the watch of Charles Kennedy, its leader from 1999 to 2006. Nick Clegg, the current leader (since 2007), is more strategic but could not undo the party’s vulnerability; he completely misread the danger from promising not to raise student tuition fees in particular. The result was that the party’s support collapsed as soon as they entered coalition with the Conservatives – even though this was a correct strategic decision. It was viewed as betrayal by many of the party’s voters and the party’s brand has been badly damaged. Though it is saying many sensible things in the campaign, and much that a lot of people would agree with, most people just aren’t listening – and its new pledges invite a sceptical response. It now relies on popular candidates to maintain its place in parliament. The party has some hard strategic choices to make after the election.

The only party that looks truly strategic is the SNP. They have had an easy hand to play, admittedly – simply to exploit the neglect of Scotland by Britain’s political class. But you can see them thinking two moves or more ahead all the time, allowing them to capitalise on their gains. They are now executing a tricky manoeuvre from the political right to the left without incurring any real damage.

But for Britain’s main parties strategy is much harder. To gain strategic advantage they have to sacrifice tactical benefits, and to take tactical risks. They need to address the generally bad reputation of politicians by being less negative and less aggressive towards their opponents; they need to embrace political reforms (on party funding and electoral systems) that may cause them short-term setbacks; they need to have open rows within their own ranks about what their parties stand for. For the Tories it looked as if Mr Cameron might embrace this agenda, but he lacked the courage. For Labour, David Miliband might have done so, but the party opted for his younger brother.

The highly professionalised and tactical focus of Britain’s political class has led to the current electoral impasse. After the election it could lead to the breakup of the Union and the country’s departure from the EU. Does the country’s political class understand the danger it is in? Will the right leaders emerge to make the difficult political decisions needed? I’m not counting on it.