This week’s Bagehot column in The Economist suggests that Labour’s policy of freezing energy prices is bad policy (actually “silly”) but good politics. It says that Labour has been too tied to “wonkery” – the design of policies that are clever enough to solve problems without the need to confront awkward choices. Their new policy is a welcome break form the current Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer. But I don’t think the policy is quite so silly – even if Labour’s suggestions about how the costs will be managed mainly are.

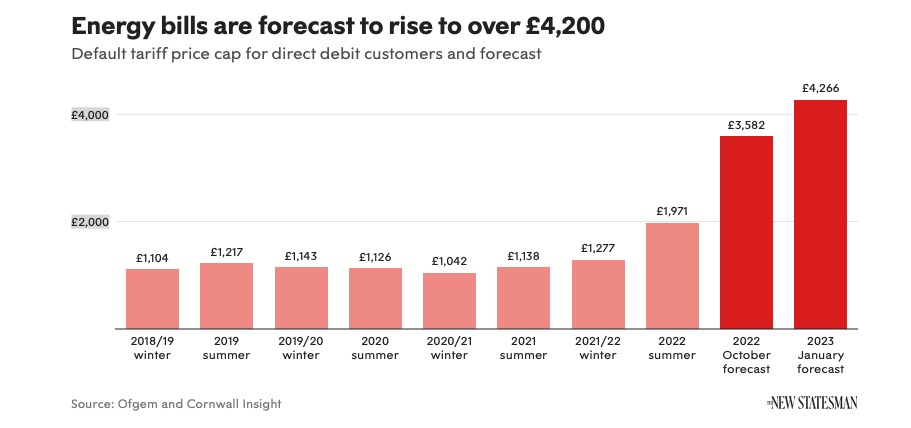

The challenge is huge. British energy prices, especially for gas, have shot up this year. But that is just a foretaste. Further steep rises are in the pipeline: the graphic above, showing annualised costs, culled from the New Statesman (featuring widely quoted projections from Cornwall Insight – who seem to be the only people making them) shows the problem. The median annual household income is estimated to be £31,400 after tax – so costs are rising from 4% to maybe nearly 14% of income for the median household, and it could be double this for the bottom quartile. Other costs are rising too, and, for most people, pay is not keeping up (many senior executives and our local refuse collectors excluded). The media has little difficulty in finding cases of extreme hardship – of people choosing between energy and food for example – and, apparently, not even being able to heat that food up. In one case publicised by BBC News, somebody was selling their furniture to pay their bills. And that is before the forecast price rises have gone through, and before winter brings in the need for heating. Overwhelmingly the public feel that the government should step in to relieve hardship – although how many Conservative Party members share this feeling, while they choose their next leader, is not clear. So far, so clear.

This is where The Economist‘s wonkery comes in. The view amongst Britain’s policy wonks is that help needs to be concentrated on those that need it most. Trying to cap the price for everybody, a policy widely favoured in other European countries, is regarded as a bad idea. For two reasons: first it wastes public funds on people that don’t need it, and second it blunts the market signal that people should reduce energy consumption, and so ease the imbalance between supply and demand that is causing the problem in the first place. This thinking has guided government policy to date. British energy prices have been allowed to shoot ahead of those in the rest of Europe – while the government is trying to target the bulk of its help to the neediest. But this bumps into a major problem. How can the government tell who to help, and who can get along without it? They have two main ways of trying to do this. The first is to help those already entitled to other help, such as Universal Credit – and the second is to ask people to apply for help, and then to assess whether they actually need it.

Both solutions are badly flawed. A problem on this scale is going to hit many people not entitled to benefits, which have become notably stingier over time. I have seen this problem in a different context: the supply of free school meals to struggling families. Many families need the help but are just above the threshold for entitlement. The problem with asking people to come forward is that many will refuse to as a matter of pride, while others who don’t need the help will try their luck, and need to be weeded out in some way, or else the system will subject to allegations of widespread abuse. This last has been the case with help for businesses in the pandemic. This problem is what I have called the Information Gap. The state does not know enough about individuals or businesses to tailor its policies to specific need. It either creates universal entitlements, helping those who are not in need, or resorts to a number of very blunt instruments, which often create political backwash.

The Information Gap is not just some technical problem that can be left to policy wonks to solve. It is one of the central problems of the modern state, and everybody in politics, wonk or not, should be aware of it. There are three general philosophical approaches to dealing with the Gap. One is to use the best efforts of the state to gather information and close the gap, compelling disclosure as required. This is the approach we associate with the Chinese Communist Party; it is highly paternalistic, and seamlessly moves into the state intruding into our private lives in unexpected ways. And the state never gets enough information to solve the problem properly. Its opposite is the libertarian approach. This suggests that the state should not involve itself in helping individuals at all. It should establish a system of security and property rights, and not much else. This thinking is popular n the political right, though not amongst populists. The third approach is solve the problem through a combination of universal entitlements and high taxes. This has recently been popularised through the advocacy of Universal Basic Income. Of course nobody, or almost nobody, advocates taking any of these three approaches to the extreme. Practical statecraft involves balancing all three approaches. Politically, though, we need to develop a sense of in which direction is the site needs to tilt at the current time.

Alas politicians rarely succeed by being honest about the difficult choices involved. Tory leadership contender Rishi Sunak seems to be suggesting that we take the more paternalist approach – but without being clear as to how the information gap is to be closed. His past behaviour in the pandemic suggests that we will accept a high degree of failure and try to shrug it off. His rival, Liz Truss, is suggesting a more libertarian approach – but without being honest about the widespread hardship and business failure that is likely to result. And now Labour is suggesting the use of universal entitlements – but without being honest that this will lead to higher taxes. All three are displaying a dependence on magical thinking. Labour’s “costing” of its new policy is laughable – but the economic illiteracy it is showing is the rule amongst serious politicians, not an aberration.

Personally I think Britain needs to move further along the universal entitlements and high tax route – an approach derided by Ms Truss, but one which the better-run European states favour. That does lead to further problems. Public services will require more discipline to improve their effectiveness, which I believe will have to come alongside decentralisation – with political accountability moving in parallel. That will require deep reforms that people may support in theory, but will resist in practice. Without reform, services will simply gobble up resources without becoming more effective. A further problem, shown in other European countries, is that tensions over immigration have to be managed. If entitlements are high, the public resents people it sees as freeloaders – and there is political mileage in stoking up that resentment, whether fair or not.

So that’s two cheers for Labour – and indeed the Lib Dems whose policies Labour seem to be copying. Alas I don’t see any sign that either party is going to be honest about taxes. But the public, surely, will start to see the need for hard choices. The careers of the two British politicians most egregious in suggesting that no hard choices are required – Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn – have both ended ignominiously.