The this week’s FT Janan Ganesh suggests that those who supported Britain’s entry to the Euro back in the late 1990s and early 2000s should own up to to their error and apologise for it. He feels that the arrogance of that generation of Europhiles is undermining the pro EU case as we face a referendum on membership. Well he won’t have me in mind. I am not a prominent politician; I wasn’t even blogging in those days. But I did have an opinion – and that was that that the country should be part of the Euro – though not at the exchange rate then on offer (about 65p per Euro). Should I hang my head in shame?

In fact this also seems to be a rather desperate line of attack by the Eurosceptics, who are at last realising to their horror that they are being out-manoeuvred. They want to discredit the whole pro-Europe cause. In today’s FT , one its other writers, Martin Sandbu, comes out with a robust defence of British entry to the Euro. He suggests that if the UK had been part of the Euro economic disaster would have been averted, because the European approach to fiscal and monetary policy would have been more pragmatically British. I have also heard a that idea suggested by a commentator from within the Euro zone, though I can’t remember who.

I’m not entirely convinced. But it at least raises the big question. It is treated as entirely self evident that the Euro is a disaster, and that British membership would have made things worse for the country. But both these are counterfactuals. We don’t know what would have happened if the Euro had never got off the ground, or if Britain had been a member.

Let’s consider the first of these. When the Euro was being formed the economies of Italy, Greece and Portugal were in real trouble. Their governments were losing the confidence of the markets; stagflation followed by hyperinflation beckoned. The Euro lifted these economies – before joining the governments were forced to bring fiscal policy under control; after joining interest rates fell dramatically. But these countries failed to deal with deeper seated problems, and eventually the chickens had to come home to roost. Membership of the Euro delayed the denouement rather than caused it. Indeed it gave these countries an opportunity to head off disaster which they failed to take. Contrast this, for example, to Belgium, also considered a bit of a basket case before the Euro, whose economy now prospers, relatively speaking at least. And for each of the other members of the Euro that ran into trouble something similar can be said. Ireland suffered the consequences of a reckless expansion of its financial system not unlike that of Iceland, outside the zone. Iceland’s crash was at least as painful as Ireland’s. Their problems reflect underlying economic weaknesses that governments failed to tackle. The signs were there. Indeed no members inside the zone seem to want to return to life outside it, with the possible exception of Germany (and Finland perhaps).

The ambiguity of Germans is understandable. The interesting thing about that country though is that they were the only, or at least the first, country in the zone to understand the implications of membership for economic management. In the early days they realised they were uncompetitive, and embarked on a programme of “real” devaluation. This was a combination of holding pay rates down and economic reforms to improve productivity. The reluctance of other countries to embrace this style of economic management is the main failure of the Euro project.

And what of the second counterfactual? What if the UK had joined? Well the first thing to be said is that the country did not do so well out of the zone. The financial crash of 2008 was deeper, and the recovery slower, than the major Eurozone economies. Britain suffered a persistent current account deficit, supported by an unsustainable exchange rate. We were in a not dissimilar space to countries like Spain and Ireland, going through a financial boom offering the illusion of wealth while not enough was being done to fix the fundamentals. It is not so self-evident that things would have been worse inside the zone.

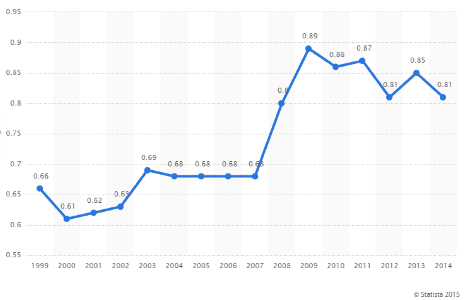

Or perhaps not. I would like to think inside the Euro the UK would have been locked into an exchange rate that suited exporting industries (like Germany after its reform/adjustment programme) and not so subject to financial shenanigans. That would have left the economy in a stronger position after the bust. But such an exchange rate was not on offer. The chart above shows the average exchange rate between the Euro and Sterling for each year of the currency (source: stastica.com). My view is (and was at the time) that the rate of 65p was high (or too low in terms of the graph). It was distorted by excessive government spending and a booming financial sector – there was a substantial current account deficit to show that it was unsustainable. It did not drop to a more realistic level until 2007-2008. That was too late. There was no chance that the government would have followed Germany’s example in conducting reforms to improve the real exchange rate – not while everything was rosy on the surface.

not on offer. The chart above shows the average exchange rate between the Euro and Sterling for each year of the currency (source: stastica.com). My view is (and was at the time) that the rate of 65p was high (or too low in terms of the graph). It was distorted by excessive government spending and a booming financial sector – there was a substantial current account deficit to show that it was unsustainable. It did not drop to a more realistic level until 2007-2008. That was too late. There was no chance that the government would have followed Germany’s example in conducting reforms to improve the real exchange rate – not while everything was rosy on the surface.

So If Britain had joined the Euro at its start or early in its existence, then the exchange rate would have been too high. Which would have made the adjustment period after the crash even more difficult. I’m not going to apologise for this because I understood that at the time (or that’s how I remember it!).

But there is a bigger issue that I will have to own up to. The design and operation of the Euro zone was flawed. There are two sustainable ways of running such a common currency area. One is part of an explicitly federal system of government, which allows substantial fiscal transfers between its members and a robust system of federal political control to match. In this system members bail each other out if they get into trouble.To judge from most commentary, you would think that this is the only way to run the zone – and that because the European polity is not ready for such a federal system, then it will never work. But there is an alternative, where each member is not so tied to the others. Each country is left to run its affairs as it sees fit, and if it can’t pay its debts, it goes bust. It requires a sovereign insolvency regime. Nobody bails failing states out.

This latter arrangement is what the Germans wanted, and it is what most Britons that supported membership wanted too. But Euro-federalists in Brussels and the southern states saw the currency as a step towards federalism. The Germans didn’t help matters by insisting on system of fiscal rules for members – the “Stability & Growth Pact” – which is only necessary if you are heading for a federal arrangement. The idea that the system was in fact of the federal type was implied by the fact that government bond rates for the different members were almost identical for much of the Euro’s life before the crisis. This was a bad sign – and yet most European leaders though it was a good one. When crisis approached European leaders were complacent. And when things went wrong, there was muddle and confusion. This problem is still not resolved.

And here I have to own up. While I saw some of the signs, I did not appreciate the full implications of this ambiguity. I thought it was a problem that could be solved by evolution from within.

I still believe that. But the politics of EU membership in Britain are toxic enough as it is. It is better that the country is not part of the tortuous politics of the Eurozone. That is why I accept the consensus that Britain probably never will be be part of the Euro zone. Or not until firstly the zone finds a new and sustainable equilibrium, and secondly that Britain sinks into an economic mire that destroys its self-confidence as an independent nation. Both are possibilities.

Meanwhile I am not a fan of an independent Sterling. It has a way of distracting the political elite from dealing with deep-seated economic issues, like our current account deficit, our inefficient underlying economy and our over-dependence on volatile financial flows. But, it has to be admitted, that, with the exception of Germany, the Eurozone members were equally blind to the self-same issues. I apologise for not appreciating that enough.