Last week a group called the “Future of Life Institute” published an open letter urging governments to pause research on artificial intelligence so that a new worldwide regulatory framework can be agreed to prevent the technology taking a highly destructive route. There are quite a few distinguished signatories, of whom the most commented upon is the technology entrepreneur Elon Musk. On the same day the British government published a paper on AI strategy suggesting a minimum of regulation in order for this country to gain a technical edge. The first development bespeaks fear and panic amongst intellectuals, and the second the political reality of countries wanting to win the race. Is the world going to hell in a handcart?

The text of the letter is here. The core of it is this series of fears:

Contemporary AI systems are now becoming human-competitive at general tasks, and we must ask ourselves: Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? Should we automate away all the jobs, including the fulfilling ones? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us? Should we risk loss of control of our civilization?

from “Pause Giant AI Experiments: an Open Letter” – Future of Life Institute

Now let’s take a deep breath. AI is important and will have a profound effect on human life. recent progress has been dramatic, and its most recent capabilities have astonished. But its impact is not necessarily benign, and there are some serious risks attached to its development. But to describe current AI capabilities as a “mind” and to suggest that it is on the road to replacing humanity in general understanding, judgement and control is to misunderstand what it is – it is classic anthropomorphism of the sort that imagines your cat to be a scheming villain. If you want to unpack this a little, a good place to go is this blog piece by Melanie Mitchell an AI academic. The interesting question is why so many intelligent people are being let astray by the hype.

For a long time, people have dreamed of building intelligence that can replicate the autonomy, command and ability to learn new tasks in such a way that any human rôle can be replaced by it. This is referred to as “general AI”. Once you leave behind the understanding that humans, and indeed animals, are animated by some form of supernatural spirit, you are left with the logical possibility of humans building something lifelike in all its capabilities. It’s just atoms and molecules after all. And of course, if we can do that, then we can make robots stronger and better than the original because we can engineer it that way. This has particularly appealed to the military, who can develop robot-powered weapon systems to replace frail soldiers, sailors and airmen, and doubtless spacemen too. And such is the confidence of modern humans, that it is widely assumed that doing so is not so hard. During the Cold War both America and the Soviet Union worried that their opponents were close to developing just such a capability, doubtless promoted by people in search of funding. Such is the grasp of military “intelligence”.

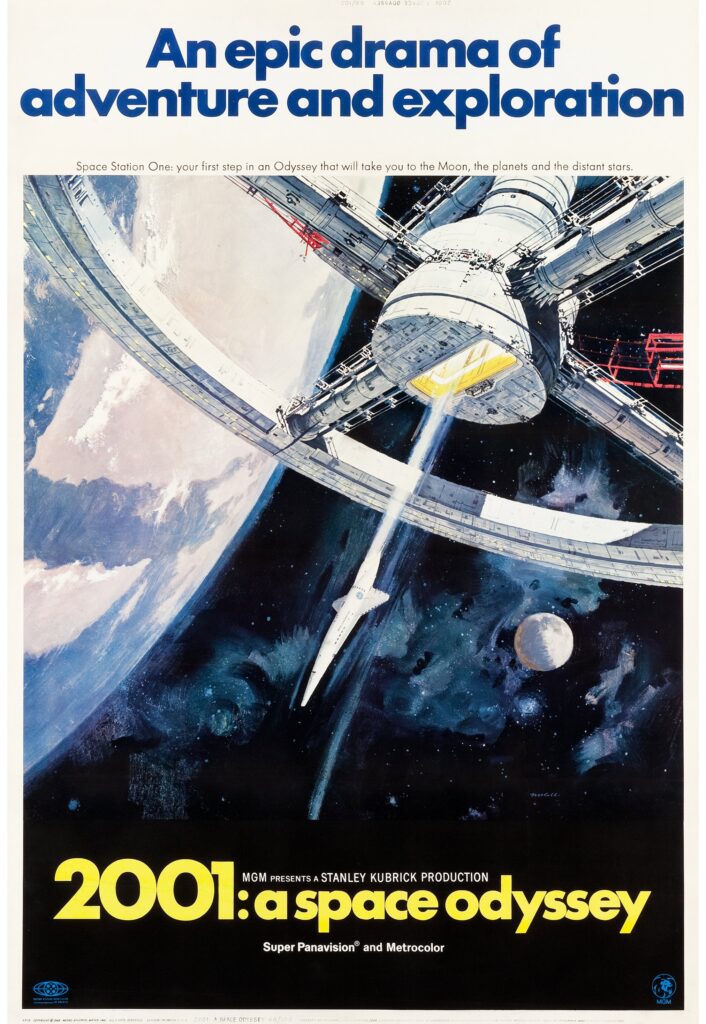

And people continue to believe that such an ability is just around the corner. In their film and novel 2001, a Space Odyssey, published in the 1960s the author Arthur C Clarke and fim-maker Stanley Kubrick speculated that out-of-control general AI would be developed by 2001. In the 2010s it was widely assumed that self-driving cars would be on the road by the early 2020s. But in 2023, instead of mounting excitement about its imminent rollout, there a silence. And now generative AI, which can manufacture very human-sounding bullshit from minimal instructions, is sparking this panic. Each wave of AI generates astonishing advances, and then seems to stop at the bits its promoters assumed were mere details. Researchers and technologists have a strong incentive to hype their latest achievements, and one of the most effective ways of doing this is to claim that you are close to bridging the gap to general AI. The people with the money often have little idea of what is or is not technically possible – not that the developers often have much idea themselves – and investing in the first successful general AI project sounds like a good deal. Just how hard can it be, after all? General AI occurs naturally.

Behind this lies a striking failure to understand what humans are. It is assumed that humans are naturally-occurring robots – machines created by an intelligence to fulfil particular tasks. Back in the days when I followed evangelical Christians there was a popular idea called “intelligent design”. This posited that the world, and animals and people in particular, were far too clever and complicated to have been created by dumb processes like natural selection, so they must have been designed by an intelligence – God. It seems that most people instinctively believe this, even if they disregard the divine revelation of the Abrahamic religions. We create god in our own image. Evolution is often described as if it were an intelligent process; DNA is described as a blueprint; and so on. Man has created God in his own image, and assumed he (well, maybe she) would create things in the way that men would. But the most important thing to understand about humans and the world is that there is no intelligent creator; there is no thread of intent; no design. It just happened. Over a very long time. It follows that trying to reproduce human intelligence through a process of intelligent design is going to be at best slow and frustrating, and at worst not feasible. Indeed a lot of breakthroughs in AI design, such as neural networks, are based on the idea that the thing should build itself, rather than be designed. But that has limits. Development is not going to be an orderly progression of achievements.

And indeed, each phase of AI development comes with inherent limitations. Generative AI, the current craze, requires massive computer processing power, and a huge database of knowledge in digital form. It is easy to see how this might be useful; harder to see how it leads to general AI. The battle over modern AI seems to revolve around training data and computer firepower. One of China’s advantages is that it has access to cheap labour to produce training databases. There is a paradox there. The idea is that in due course that the robots will find and produce their own training data – but problems abound. Indeed for AI to be useful (including self-driving cars) I think it will be necessary to simplify the the world so that it can be represented more accurately in training data. But that makes it of limited use in the wild.

And so the hype cycle goes on. At each turn we will be distracted by the prospect of general AI rather than tackle the more important issues that each iteration throws up. In the case of generative AI it is how to deal with the misinformation and prejudice lurking in the training data, that the technology won’t be able to recognise – when its “reasoning” is so opaque that it can be hard to spot what is causing the problem.

And what of the British government’s AI strategy? I haven’t read it so I can’t comment with authority. Generally I am suspicious of politicians jumping on bandwagons – and any call to invest in this or that technology because otherwise we will be left behind in the global race is suspect. Economic advantage usually accrues either from developing things in areas where people are not already heavily invested, or from copycatting after somebody else has done the difficult bits. But in seeking to develop a light-touch regulatory advantage while the European Union and the US are tangled in moral panic, and China over fears of loss of party control, it might be onto something – though it is hard to see that the US will in the end be weighed down by over-regulation. On the other hand the US and China have advantages in access to finance, computing power, and data – while the multilingualism of the EU perhaps offers an advantage to them. Britain may simply become a base for developing intellectual property owns by others.

Anyway, a it is hard to see what a six-month pause could possibly achieve. Humanity may reach general AI in due course. But not for a while yet.