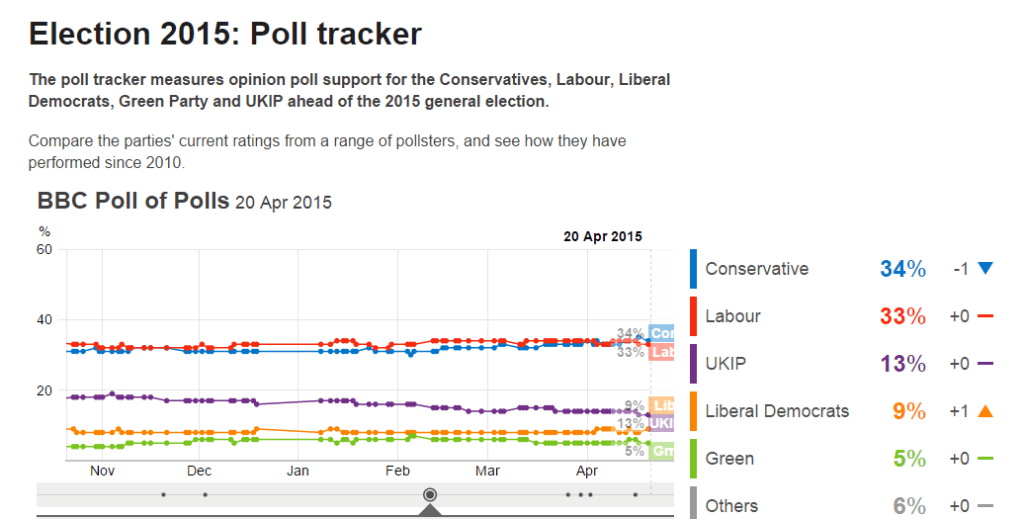

There is now less than a week to go before Britain’s General Election (Thursday 7 May).The tension mounts amongst those that follow these things. So far the opinion polls swing this way and that, but on average remain nearly static. In the BBC Poll of Polls the parties haven’t wavered more than 1% from 34% each for Conservatives and Labour, 14% for Ukip, 8% for the Liberal Democrats and 5% for the Greens. But things could change significantly in the last week.

Much of the important movement remains invisible. It is in 100 or so competitive seats (I’m excluding Scotland from my commentary for now). Significant movements here do not show in the polls. The Conservative and Labour parties, easily the best resourced, are cranking their campaigns up a gear. And their main targets are voters who are supporting the smaller parties: the Lib Dems, Ukip and the Greens, and no doubt Plaid Cymru too in Wales. In Labour-Tory marginals these voters are relentlessly being told that a vote for their preferred party is wasted: the real choice is between the big boys: and you don’t want the other side to win, do you? In seats where these other parties are in contention (and especially the 46 English and Welsh seats held by the Liberal Democrats) the effort is no less relentless. The Conservative leader led an attack on the Lib Dem seats in the southwest this week; Labour are no less determined to capture seats from the Lib Dems. The single Green seat of Brighton is under fierce attack by Labour. There is a massive battle in seats such as Thanet South where Ukip are in contention.

The smaller parties’ voters seem a softer target than trying to pick off voters directly from the other main party. We don’t know how successful this push by the big parties will be. But the Lib Dems are widely expected to lose over 30 of their 57 seats; the Greens could lose their only seat; Ukip might be left only with their by-election win of Clacton South. Of course I hope that the Lib Dems will do better than that (and more than hope – I will be stepping up my personal contribution to their efforts). But there is a strong prospect that the two big parties will win all but 25 of the 573 seats up for grabs in England and Wales. Two-party politics will have triumphed, even if the other parties win a more likely 35.

That is worth a little reflection. The conventional wisdom has been that two-party politics is over, The major parties cannot to get beyond 68% of the total vote between them (it used to be in the 90s). The BBC election logos show many colours; we had our first seven-way party leaders’ debate on the television. But once the results are in, you can bet that this will be tossed aside. There will be no real pressure for electoral reform, and the normal service will resume. Insiders in the main parties, the media and the civil service will heave a sigh of relief. The interval of coalition government involving the Liberal Democrats will be just a bad dream.

Except of course there is Scotland. This has been bit of a one-party system, with Labour dominating parliamentary seats. It still looks like being one-party system – but this time with the SNP in charge. Their success may well mean that the two big parties still cannot dominate the UK parliament as they once did. But that only goes to emphasise just how much the country’s electoral system dominates politics. It is a winner-takes-all system, where the aim is to destroy your opponent, not to promote your positive values. The electoral reform proposed in 2011, the Alternative Vote, probably wouldn’t have changed this.

The parliament may be very unrepresentative. Many supporters of other parties may feel disenfranchised. But the people in the system just don’t care. All they think about is the potential prize of winning big and the vast bonanza of power and patronage that can bring. And to win big your party doesn’t have to be popular: you can do so if the other party is weak. And there always tempting fissures to exploit.

In the self-view of the main party supporters (including the SNP in this case), there is no particular problem about this. They haven’t really accepted the right of other parties to exist. In yesterday’s Question Time show the Labour leader Ed Miliband thought it was fine to suggest he would try to implement the Labour election manifesto unmodified whether or not he had a full electoral mandate. He seemed to have no notion that this might be undemocratic. When the Liberal Democrats joined the Conservatives in coalition this was seen as treachery by Labour supporters. The major parties would prefer a one-party state best of all – a situation they have sometimes achieved at local level. To them this would simply be a natural affirmation that they are in the right. They may concede that the world has to be divided into tribes of left and right but that is as far as they will go (though for the SNP haven’t got beyond the one-party state idea). Since these are the people who control what happens in our political system, is there any chance it will change? Should it change?

This will be among the big questions we English (and the Welsh) will need to face after the election. About a third of people vote for parties other than the big two. This would surely be more if the pressure to vote for one of the big two wasn’t so great. Politicians’ standing in the public eye is not high. This should be a good moment to promote electoral and other political reform.

It could happen: it did in New Zealand in 1996. But to do so the Labour and Conservative parties have to come under existential threat – the sort of threat of implosion that both have suffered in turn in Scotland. This is possible. If Labour end up in government, as still seems most likely, they will be riven by divisions and disappointed expectations. The Conservatives could be fatally divided by their attitudes to Europe.

Personally I think that the Liberal Democrats should put political reform at the heart of their agenda after the election. It used to under Paddy Ashdown in the 1990s, but subsequent leaders diluted it. They then need to assemble a coalition for reform, perhaps linking up with the Greens (though Ukip might be a step too far!) – and any splinters that the other parties might produce. But the battle will be an uphill one. The party has its own tendency to the winner-takes-all idea. But at 8% in the polls and its former electoral strategy in ruins, some fresh thinking is called for.