It’s unwise to bet against Donald Trump. Last autumn he hit a low point when candidates he backed performed badly in the US mid-term elections. But to see how effortlessly he is leaving his Republican rivals for the presidency in his wake leaves me gasping in a sort of admiration. He does this by breaking every piece of advice and common sense that crowds my feed on LinkedIn. Any person who seeks to be effective in politics, or management, needs to understand why Mr Trump is so effective at self-promotion – even as he is so ineffective at pretty much anything else.

As I was pondering this, I read an article on “The truth behind emotional intelligence”, by FT columnist Janan Ganesh. A lot of what clogs my LinkedIn feed is promotion of emotional intelligence. Mr Ganesh complains that people are muddling emotional intelligence with niceness. In fact many nice people have little understanding of the emotional dynamics of the situations they are in and are consequently ineffective – while many nasty people are extremely good at manipulation, which is founded on strong emotional intelligence. He uses as his example Shakespeare’s villain Iago in Othello.

I agree. I first encountered the idea of emotional intelligence on a residential management course in about the year 2000. It was profoundly influential for me. Our trainers were about promoting management effectiveness, not niceness. On the one hand I found the course very reassuring. I proved extremely good at understanding emotional dynamics at work. I was a good listener. As Mr Ganesh points out, emotional intelligence requires listening, and quiet people are usually better at it than the noisy ones who trumpet their emotional understanding. And I was, and I still am, a quiet person – often painfully so. But, and my trainer was clear about this, that quietness got in the way of my effectiveness as a manager. It held me back from being as assertive as I sometimes needed to be. This summed up my professional career very well. While my quietness somewhat typecast me as being very clever in an introverted, geekish way – a large part of my effectiveness actually derived from listening skills and ability to navigate the emotional chess of office politics. But on the other hand I lacked something big and important, and that held my career back. I flourished best when I worked among a small (ish) team of people who worked well together. After we were taken over by a large multi-national bank I quickly started to fade, and took voluntary redundancy.

But what has that got to do with Donald Trump? Well the first point is that Mr Trump is pretty much everything that I am not. That assertiveness that I lacked is overwhelming in him. He is not good at empathy. And yet Mr Trump succeeds like no other politician in forging an emotional connection with his supporters. A recent poll suggested that 71% said that what Mr Trump told them was likely to be true, compared to 63% for friends and family, and just 43% for religious leaders. That, presumably, is because Mr Trump understands what they think the truth is, and feeds it back to them. Those ratings would collapse if he got up and said that, for example, warnings about carbon emissions were well-founded and that all coal mining in the US should cease. But what gives Mr Trump that understanding? Clearly listening of some sort is happening. In the past I have called this right-brained genius – building on the idea that the left side of our brain is our rationale side, and the right our intuitive side. Advocates of this idea suggest that in the West we overdo left-brain thinking, and we should be more in touch with our right brains. But the right brain has its dark side – Mr Trump is very in touch with his.

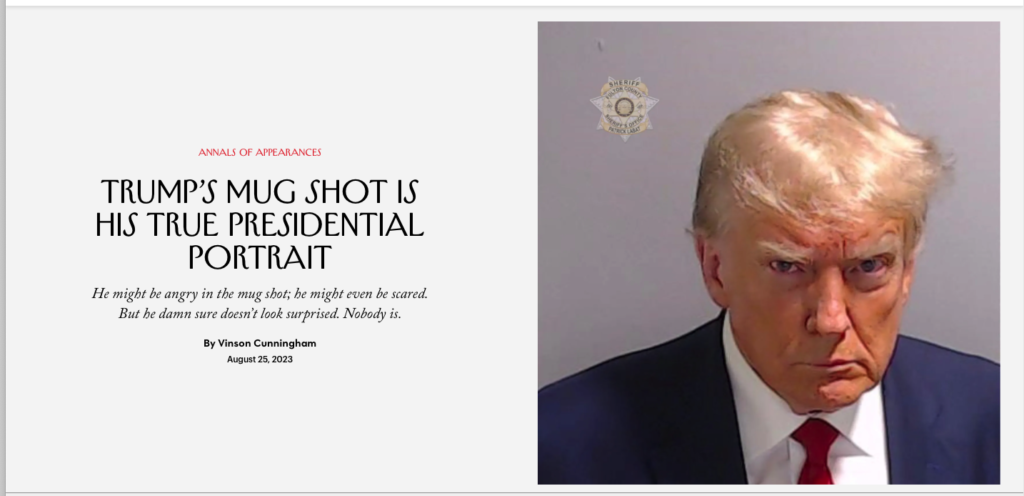

But that explanation only takes you so far. His Republican rivals listen to the same people and pick up the same messages. Mr Trump builds on his understanding in his public presentation. This is rambling and incoherent (to an extent you would not appreciate if all you heard was edited sound bites), but delivered with a sly sense of humour. This comes over as authentic – no speechwriter could deliver the the same effect – and he makes his audience feel that they are insiders. All the attacks on him, he says, are attacks on you. The more he is attacked, the more his supporters like him. He uses his recent legal troubles to boost a collective sense of victimhood – most recently in his recent use of his Georgia mugshot. He is able to channel all his audience’s frustrations with the world. It is, once again, very right-brained. Even the best paid political consultants cannot coach their clients into achieving something similar – anyway he got there first, which adds to the authenticity. And the more outrageous he is, the more newsworthy – and the more people are talking about him and only him. Meanwhile others who entered politics to achieve serious things, and spend time trying to understand the world, are most unlikely to have the right head-space for that type of behaviour.

There is an evil to Mr Trump’s evil. It is entirely about self-promotion. Naturally he thinks that the world would be a much better place with him in charge, because nobody understands the world like he does. But he is fundamentally un-serious about government and his ego undermines any attempt to implement serious policy. In power he might do some good things, but overall it would be a major step back for the world.

Will he win the presidency? His campaign is better organised and more savvy than in 2016 when he first won. He is running rings around his Republican rivals, even those who are much more capable and qualified than he is. But his challenge will be to reach out to beyond those who worship him – to those who have a better grasp of his weaknesses. That will be hard but it isn’t hopeless. Many have little faith in the Democrats, and their likely candidate, President Biden, has weaknesses of his own. If Mr Trump wins his party’s nomination he will have momentum. His odds of success are better than they should be.

What is the message for the rest of us? Understanding of the emotional side of life is critical to success, whether or not you call it emotional intelligence. But those who possess it are often less effective in other ways, because listening is demanding work and can come at the cost of assertiveness. For some people intuitive emotional connection can substitute for this. But that brings its own dangers.