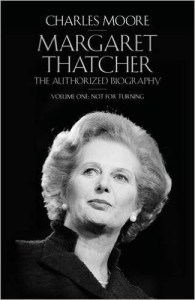

I have recently finished reading Charles Moore’s excellent first volume of the authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher. I wanted to read this as I inhabit a bit of a left wing bubble, politically anyway. We project cardboard fantasies onto Tories, as selfish, rich cynics. But we need to understand their true humanity and complexity – and Mrs Thatcher is such an important figure,that she is a good place to start. It is proving timely since some supporters of Labour leadership contender Jeremy Corbyn are suggesting that she offers an interesting precedent. Somebody who achieved power and dominance in spite of despising the political middle ground.

I have recently finished reading Charles Moore’s excellent first volume of the authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher. I wanted to read this as I inhabit a bit of a left wing bubble, politically anyway. We project cardboard fantasies onto Tories, as selfish, rich cynics. But we need to understand their true humanity and complexity – and Mrs Thatcher is such an important figure,that she is a good place to start. It is proving timely since some supporters of Labour leadership contender Jeremy Corbyn are suggesting that she offers an interesting precedent. Somebody who achieved power and dominance in spite of despising the political middle ground.

It is, of course, easy to dismiss the comparison of an ambitious and conventional careerist like Mrs Thatcher with the maverick Mr Corbyn, who has discovered serious political ambition late in life. She had at least had been a cabinet minister, and had some kind of relationship with most of the important people in her party before her bid for power in 1974. Still, she succeeded in spite of rejecting consensus, and in the face of massive scepticism, while having solid grassroots support.

The book covers Mrs Thatcher’s early life up to the conclusion of the Falklands War in 1982, at which point she truly started to dominate politics. It is a fascinating story. Let me offer a few observations.

The first is not relevant to Mr Corbyn’s situation. It is that there was something quite liberal, and indeed Liberal about Mrs Thatcher’s political outlook. Her father had been a Liberal, and a senior local politician. If you had to pick one word that summarised her outlook it was Freedom. She did not believe in a ruling class that was born to rule. She wanted everybody to be able to access what society had to offer – though she assumed that they would have to work for it, rather than let things be handed to them on a plate. She hated trade unions because they underwrote a system that stifled freedom: but she admired the way that they stood up for the weak and voiceless. You just have to remember how stultifying the political consensus of the 1950s, 60s and 70s had become, not to mention the ever present Cold War mentality, to understand how liberal beliefs might drive you to the right rather than the left in those days.

In only two serious ways can I think that Mrs Thatcher’s beliefs conflict which core liberalism as I understand it. One was that she was fiercely nationalistic – although that may be more of a failure of imagination than principle. She swallowed whole a traditional view of English history – which she saw no need to question. Secondly she believed profoundly that people should strive to better the lot of their children – to the point that inheritance of your parents’ assets was a fundamental right. Modern liberals want people to strive for their children, of course, but think of legacies of property and money as a barrier to freedom of opportunity.

It need hardly be said that Mrs Thatcher had no time for the Liberal Party itself – who were often here main opponents in her local seat in Finchley. To her (and her father) Liberals had betrayed Liberalism.

A second point is that her advance from Leader of the Opposition to Prime Minister was precarious. She nearly lost the election in 1979. Her most reliable ally was a deep public distrust of Labour, following years of economic failure – high unemployment, inflation, and awful government finances. Trade union power, showing contempt for elected politicians and the rule of law, was a further cause of public disgust. But she did not have any convincing economic narrative with which to to oppose Labour, and that undermined her public appeal as the election drew close. The previous Conservative government, in which she had served, was widely regarded as a disaster. Her own economic policies were unclear, and to the extent they were formed, were doubted by most of her party.

This, of course, may be one thing giving Corbynistas hope: that Mrs Thatcher won in spite of lacking a clear economic narrative. It runs counter to the Labour centrist narrative that the party will only be electable if it follows the conventional economic wisdom, and much of the Tory economic narrative. But Mrs Thatcher’s lack of economic narrative nearly undid her. And for it to work the Tories will have to look a lot more financially incompetent than they do now. As I have written before, the British economy could certainly go off the rails in the next four years. Growth could fail; another banking crisis could strike. But the problem for the left is that any such new crisis might make the anti-austerity narrative look less credible rather than more so. Indeed, the best argument that can be made for the government’s excessive plans to reduce government expenditure is that they will be a better place to start if the economy at large disappoints.

And the third observation is how long it took for Thatcherism to emerge after she became Prime Minister in 1979. In her initial Cabinet she was outnumbered by sceptics (“the Wets”). The government had to deal with a raging economic crisis – and that absorbed its full attention. Her strategy was what today would be called austerity – cuts in government spending, and some tax rises, to try and bring government finances under control. It was all she could do to keep her Cabinet more or less behind her. This has echoes of the first Coalition years after 2010 – with an important difference: interest rates were sky high in the early 1980s in order to deal with rampant inflation. (And, I would add, the Coalition Cabinet was considerably more united). At the time this was not a particularly ideological struggle; much of the impetus came from her Chancellor, Sir Geoffrey Howe, who was of the political centre, and with whom she did not see eye to eye. It was more a matter of asserting political control, based on age-old Treasury orthodoxy. And it is striking just how much of the problem of economic management derived from nationalised industries – which included steel, cars and coal – as well as energy and the railways. State control had allowed awful management to take hold, abetted by trade unions who had no conception that economic efficiency should be a political priority.

There is a tendency in the left to look back on the Keynesian consensus years from the 1950s to the 1970s as a bit of a golden age (though I would suspect that Maynard Keynes would turn in his grave to have his name attached to those policies!). The consensus favoured a highly active government, that tended to nationalise large industrial concerns when they got into trouble. But the country stumbled from one economic crisis to another from the 1960s onwards, and after the oil crisis of 1974 economic collapse (hyperinflation as the government was unable to pay its debts) beckoned. If Mrs Thatcher had failed, and been replaced by a government that was less determined to tackle government finances, in the name of Keynesian demand management, then economic collapse of some sort was surely the most likely outcome.

The emerging economic problems of the 2010s and 2020s take an entirely different form. Its symptoms are slow economic growth, an uncontrollable business elite accruing much of the wealth to itself, and the disappearance of stable, middle order jobs. These are trends brought about by changes in technology, the world economy, and demographics. The political right does not have the answers. But neither does the left… though they are both right about some things.

Mrs Thatcher is a hate figure on the left, but it is not an exaggeration to say that she saved Britain from economic collapse, with a lot of the hard work being done in those first, precarious years of power. What emerged was a less equal and less secure society, but one that was overall much more prosperous. And it functioned in a way that the previous one had become unable to – consumption and production were reconciled. This achievement required a combination of steely determination, the support of an inner coterie of determined supporters, and political skill in bringing along people who did not really believe in what she was doing.

And Jeremy Corbyn? There are similarities, but it’s more than hard to see Mr Corbyn and being a Mrs Thatcher of the Left.