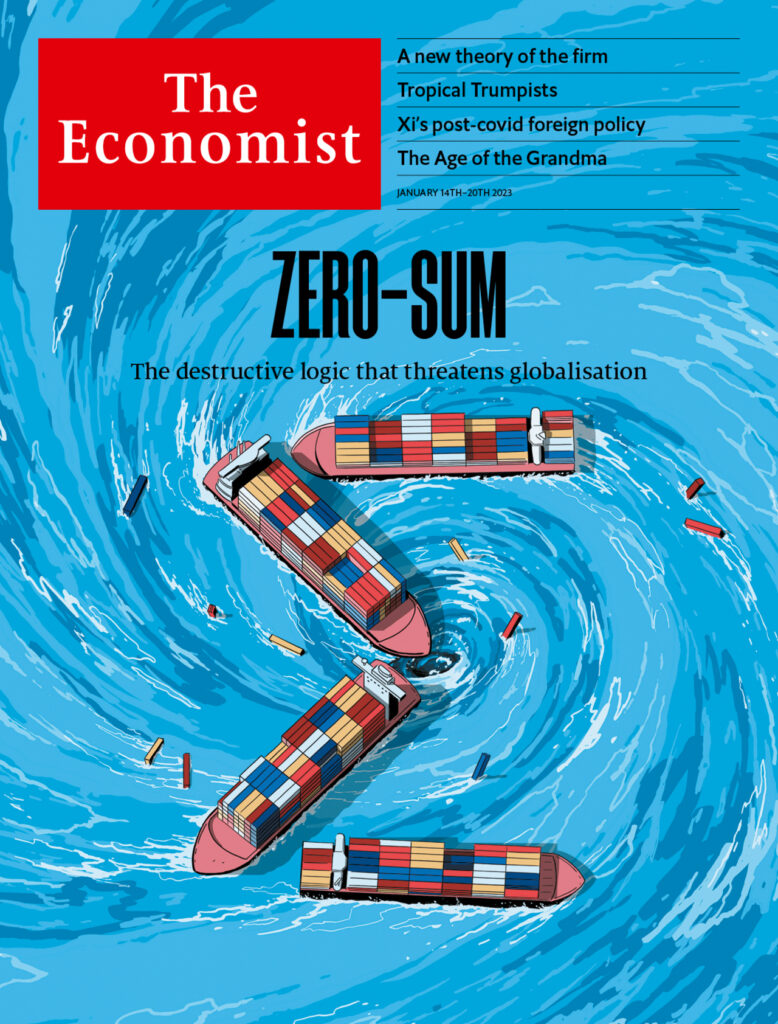

Last week’s Economist led on the dangers of changing political attitudes to world trade. The paper suggested that the rise of “zero-sum thinking” threatens capitalism, liberal democracy and the livelihoods of many. But we live in a world were the conventional wisdom of economists is being challenged – from inflation to interest rates to economic growth. The conventional wisdom on trade needs to be challenged too: not because the economics is wrong, but because the context has changed.

There are two central foundations to economists’ understanding of the benefits of trade. One is the logic of comparative advantage, one of the first insights of modern economics when it got going more than two centuries ago. What matters when resources are constrained (as they almost always are) is opportunity costs, and not absolute costs. It is more efficient for for a less productive supplier to produce goods, if the more efficient one is better able to produce other goods that are in short supply. It is one of the first things economics students are taught, and one of the most important challenges to “zero-sum thinking”, which suggests that imports are bad because they put local people out of work. Those people can be redeployed to make things things more productively in world terms, meaning that everybody can benefit.

The second foundation for the economic benefits of trade is economies of scale and the benefits of specialisation (or economies of scope). Industries may not have critical mass in their own market – but through trade they can access bigger markets, benefiting everybody. This idea can work alongside comparative advantage (the concentration of watchmakers in Switzerland presents economies of scope and scale, which in turn leads to comparative advantage, for example). That makes them easy to muddle. Economies of scale and scope do not necessarily lead to comparative advantage, and you can have comparative advantage in a particular area without economies of scale or scope. This needs to be picked through with care – which alas The Economist seldom does. Now let’s step back and look at how world trade has evolved in the last 40 years or so.

The massive explosion in global trade in the 1990s and 2000s is mainly explained by comparative advantage. The thing to understand about comparative advantage is that it is driven by differences in economic structure, which create differences in opportunity costs: it is a function of difference. China, the largest driver of this surge in global trade, was a very different place to the developed countries it traded with in 1990. A vast number of people were still employed on the land, in highly inefficient agriculture; in the developed world the agricultural workforce was nearly insignificant, while producing much more food than it could consume. By shifting workers from agriculture to manufacturing in China, a lot more manufacturing goods could be produced, with any shortfalls in agricultural production made up for by developed world production with a negligible increase in workforce. This meant that Chinese manufactured goods were dirt cheap, while its agricultural produce was expensive – a colossal opportunity for world trade, even if Chinese manufacturing productivity was much lower than in the developed world. The process worked something like this: low agricultural productivity ensured low wages; low wages meant cheap manufacturing products, even with low manufacturing productivity. The picture was a lot more complicated than this – it wasn’t actually a case of China importing grain while exporting washing machines (they imported more capital goods than food) – but comparative advantage was the driver.

That is all Economics 101. But while economists understand how comparative advantage works in principle, they are surprisingly ignorant of how it works in practice. It has improved impossible to model the dynamics of comparative advantage in a way that produces the detailed results and predictions that are most economists’ day job. So, after they have completed their undergraduate studies, few economists think much about it. If they did they would me more alive to the issue of convergence. The Chinese economy, like the Japanese and South Korean economies before it, did not stand still. Productivity shot up, especially in agriculture, and the agricultural workforce rapidly diminished, while that of manufacturing and services rose. Convergence with the developed world happened at astonishing speed, and as that happened the differences that drove comparative advantage diminished. Developed countries started to find Chinese products becoming more expensive. The incentives for long range trade between China and the rest of the world diminished. This hurt developed countries much more than it did the Chinese – as the Chinese benefited directly from increased productivity and rising wages. It is, I believe, one of the reasons for sluggish growth in the developed world since the great financial crisis of 2007-09, though it is almost never mentioned as a factor (and certainly not by The Economist), in spite of the great economist Paul Samuelson drawing attention to it.

This is where the second factor can come into play – economies of scale and scope. In Europe, for example, the leading economies converged in the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries. Comparative advantage diminished. But, after the Second World War, trade within the continent flourished, so clearly something else was behind it. Why, for example, did Germany, France, Britain and Italy all have substantial car industries, all with a lot of cross-border trade? This shouldn’t happen under comparative advantage, unless the cars each country made were somehow very different from each other. In fact the economics of motor manufacture meant consolidation into larger and larger firms was required to be competitive. Cross-border trade gave consumers more choice, and the other benefits of competition, if their own country only had room for one or two car firms. As Europe developed its single market, economic benefits flowed – but on nothing on scale that flows between more diverse economies. There are two sorts of benefit here. The first is that the benefits of economies of scale lifting productivity; this can work in quite a similar way to comparative advantage, with some countries specialising and others happy to have cheaper products (the aero industry is a bit like this). The second derives from good old fashioned competition between businesses in different countries. This is very different, as this only works if multiple countries are making similar products. We must also bear in mind that as the gains or more limited, it requires a level playing field to work; if one country suffers a systemic disadvantage, such as high transport costs because they two oceans away, then the benefits of trade diminish. That is one reason that Europe had to develop detailed rules for free trade, while the Asian economies’ rise was based on much cruder arrangements, such as World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

The important thing to realise about economies of scale and scope is that they are dependent on technology and not any iron logic of economics, as is the case for comparative advantage, although you wouldn’t think it from the way many executives from large businesses talk. And technology changes with time. The late 20th Century was particularly good for economies of scale, but that is changing. And that is for two reasons. The first is the rise of technologies that diminish the costs of short production runs and individualisation (indeed the same edition of The Economist featured this in its business section – a new theory of the firm – one of the articles featured on the cover). The second is the diminishing importance of manufactured products in the economy as whole, compared to services, such as healthcare, which are largely untradeable. All this points to reduced benefits from trade, especially between big geographical blocks like America, Europe and East Asia, as opposed to within them.

Where does that leave the current debate on trade? The first point is that I don’t think the benefits of trade are diminishing because of political obstacles; I think those political obstacles are arising because the benefits of trade are diminishing. The second thing is that, for developed economies, there is no great box of goodies that can be unlocked through trade liberalisation to help flagging growth along. Doubtless there are further benefits to be had – and especially with less developed countries if done in the right way, but not on the scale that saw the economic transformation of the 1990s and 2000s.

Now let’s look at biggest specific issue bothering The Economist – the problem of US government subsidies for green industries. Europeans are worried that this will make their own industries uncompetitive. That is a legitimate worry, but if Europeans match those subsidies with their own, the damage will be limited – and, indeed, it might hasten the transition to clean technology, with the benefits that will flow from that. The Economist worries that it will lead to inefficiency and, horror, duplication. And yet duplication is a prerequisite of competition.

Still, trade remains integral to the modern way of life and deserves continued political attention. For some things, the importance of both comparative advantage and economies of scale and scope remain undiminished. Only a few countries have direct access to metals such as cobalt and lithium, which play a critical role modern industries. And serious economies of scale or scope remain in others, such as the mining of iron ore (Australia has unmatched scale economies), or the manufacture of advanced microchips (Taiwan leads in scope economies). But the key the issue is not just economic costs, it is the potential for serious dislocation if supplies are interrupted. The modern economy contains many bottlenecks. We have to balance the benefits of short term cost savings with the risks of natural disaster and conflict. Alas the solutions are likely to make manufactured products yet more expensive.

The reason for the rise of “zero-sum thinking” is that the economics of trade is moving in that direction too, though the benefits of free trade remain substantial. It is not surprising that other issues loom larger than trade freedom, such as security of supply and the need to accelerate the transition to clean energy. It is easy to understand why The Economist wants to turn the clock back to the days of easy trade gains and steady economic growth – but it does not help prepare its readers for the hard choices ahead.