Our new prime minister, Rishi Sunak, says that Britain faces a profound economic crisis. I don’t disagree – few will. Neither do I disagree with his statement that hard choices lie ahead. I almost certainly will disagree with him what the right choices are. We are entering a period when politics matters. But we need to understand more about the mess and how we might progress.

Liz Truss, Mr Sunak’s predecessor, presented a clear narrative to explain the country’s economic ills. A timidity in the British ruling elite, abetted by the “abacus economics” of the Treasury, has stifled private enterprise, leading to a bloated public sector accompanied by low economic growth. She saw that a combination of lower taxes and deregulation could correct this, deliver economic growth, and that, thanks to the wealth thus generated, the country would be able to afford an acceptable level of public services and welfare safety net, together with improved state pensions. She thought that she could kick start the process with tax cuts. The overarching narrative may or may not have substance, but the timing was all wrong. The result was the shortest prime ministerial stint in British history.

Ms Truss was rare in offering us a clear narrative. Mr Sunak will not make that mistake. Clarity divides, getting in the way of the coalition building that successful politics demands. But a clear narrative helps the rest of us decide which policies to support. I will attempt one of my own.

My story starts in the middle of the last century. Britain was an industrial powerhouse, with a strong belief in free trade, though this regularly caused political controversy. Before the Second World War, though, this was marred by widespread poverty; the country had not found a good way of spreading economic (or any other) wellbeing across the whole of society. And then came the war. The necessities of the war ushered in a period of massive state intervention that followed a lot of the principles of socialism. Food was rationed, but people were amazed that levels of nutrition improved, as the diets of the poorest in society improved. Meanwhile the British war economy produced wonders of production and ingenuity, combining state direction with private initiative. People saw that a new way was possible, and this was brilliantly articulated by the Labour leader Clement Attlee, who reassured the middle classes with a particularly British slant on socialism, and Labour won an overwhelming parliamentary majority in 1945. He ushered in a period of profound welfare reform and the nationalisation of key industries. Labour lost power in 1951, but the landscape was so profoundly changed that most of the reforms were supported by a political consensus.

There followed two decades of what many regard in hindsight as a golden age. Economic growth was rapid, living standards advanced, poverty reduced and life expectancy dramatically extended. Many transitioned from working class to middle class. An expanding working population and an industrial revolution in the development of consumer products were the drivers. But all was not well. Other countries were doing better. Britain was steadily losing its place among the front rank of industrial powers, to America, to Germany, and even to Japan. Each of these countries turned into export powerhouses, while Britain, relatively, declined. What was happening? Poor management and a relative lack of investment were to blame, along with some bad luck (the crash of the Comet airliner in the 1950s dealt a body blow a world-leading aviation industry). A lot of this had to do with the fact that large parts of the industrial heritage was now under public ownership, and this increased as industries, notably the motor industry, started to fail and led to a clamour for government intervention. The government either starved nationalised industries of investment (the water industry for example), or squandered unbelievable sums on ill-conceived investment programmes (notably nuclear power). There were exceptions to this general mis-management, of course, such as the switch from coal gas to natural gas for domestic use. But by and large decisive management was replaced by consensus-building and political grandstanding, and the constraints of government financial management. By the 1970s nationalised industries were a by-word for bad management. Meanwhile the private sector was weighed down by high marginal rates of income tax (top rate 83%, or 98% for investment income by the mid-1970s) and corporation tax (52%).

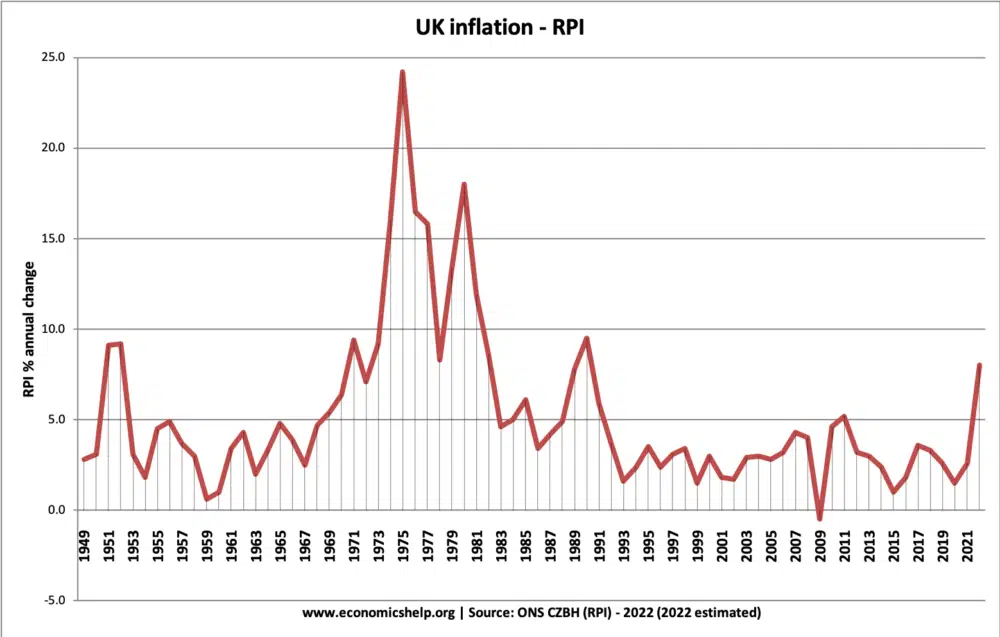

The 1970s were a time of profound economic crisis, with many parallels to now. Energy costs rocketed with two Middle East crises following the Arab-Israeli war of 1973 and the Iranian revolution of 1979. Inflation took off, and policymakers struggled to respond, as this came alongside rising unemployment (which we don’t have now, or not yet). In 1972 the Conservative government of Ted Heath tried to break the deadlock with tax cuts and more public spending (I can still remember the party political broadcast promoting this – I was 14), in a move reminiscent of Ms Truss’s failed budget. This quickly collapsed into disaster, and the government was locked into a confrontation with the miners’ union, amongst others. Harold Wilson’s Labour government of 1974 did not make things much better. Unions were able to block any serious economic reform.

In 1979 came the election of Margaret Thatcher and the Conservatives. Mrs Thatcher brought with her a new economic philosophy of reducing the role of the state. She started to reform the nationalised industries preparatory to privatisation. She cut marginal rates of income tax (though putting VAT up to maintain the overall tax take). At first things seemed to be going very badly. Inflation persisted, unemployment climbed, and nationalised industries played havoc with government finances. But by 1982 things were getting better. She received a political boost from the Falklands war, while Labour seemed to be imploding. A new party, the SDP (which I joined and have never left), offered a diversion, but failed to break Britain’s electoral system, even in alliance with the Liberals. Mrs Thatcher won a landslide majority in 1983, and quickly became politically more secure. Inflation was tamed and economic growth returned. This period remains a matter of bitter controversy. Many say that her success was based on the exploitation of North Sea oil. This was clearly a factor but her economic reforms, especially the privatisations of the energy, telecoms, steel and motor industries, clearly helped. Another factor that proved of benefit, though perhaps more so later, was the development of the European Single Market, of which Mrs Thatcher was one of the architects. Prior to this European product and labour markets had been badly fragmented. The European Economic Community had tackled tariff barriers, but non-tariff barriers remained high. These were progressively dismantled, so that Europe could follow America in the benefits of a large domestic market for many goods – and labour. Britain became a favoured European base for American and other countries. But while this progress was happening a lot of industries, notably the coal industry, collapsed under foreign competition and changing production technology. This has coloured Mrs Thatcher’s memory ever since – as she saw no reason to soften the blow as swathes of the country went into industrial decline.

One of the driving forces of change was globalisation. Increasingly the Far East became a source of cheap industrial imports. This started with Japan, and then moved on to South Korea and Taiwan, amongst others. Falling import prices became one of the chief sources of improving living standards, but it hastened the decline of former industrial heartlands. By the 1990s we see taking shape some of the main outlines of the current British economy. The country became a major net importer of manufactured goods, only partially offset by a booming service industry. At this point the books were being balanced by net oil exports. But some areas of the country were doing much better than others.

Labour under Tony Blair took over in 1997. Mr Blair sought to maintain much of the Thatcher legacy, but with an important difference. After 2001 in particular he expanded the public sector, through expanding public services such as health and education in particular. In these years a powerful myth took over the British political class. You could solve the conundrum of getting Scandinavian-level public services and welfare with American tax levels though allowing economic growth to expand level of tax receipts. But the politicians failed to understand the source of Britain’s growth in the early 2000s. This was largely driven by three factors. The first was an acceleration of globalisation, enabled by internet technologies and driven by China. I remember looking at the components of Britain’s consumer price inflation, which was about 2% per annum. The prices of manufactured goods were falling; this allowed 4% inflation in many services to be balanced out. And pay tended to follow the services figure, staying consistently ahead of overall inflation, and so leading to improved living standards. The second factor was a dramatic increase in European immigration. By the early 2000s many parts of the country were experiencing labour shortages. The baby boom was over, and the process of bringing women into the workforce largely complete; pension schemes were only slowly catching up with increased life expectancy and the proportion of retired people was growing. But the European Union at this point admitted Eastern European countries with a workforce that wanted to improve its living standards by working abroad. Poles and others flooded in and the demographic crisis was averted. Inflation was kept at bay, the second major component of growth. The third factor was the rapid expansion of financial services, and especially the banking industry. Many banks made big profits, giving the City of London the air of a boom town, inflating the property market, and generating significant capital taxes. Pretty much all the increase in recorded productivity in the early 2000s came from the banking industry, alongside “business services” (management consultants, lawyers, accountants and others feeding off the banking boom, as well as juicy public sector contracts), and the now-declining oil industry.

None of this was sustainable, and the moment of truth arrived in 2007, when the world banking crisis developed. Those big banking profits, and the productivity gains that came with them, were exposed as fiction, and the industry experienced massive write-offs. Meanwhile the globalisation boom peaked, as China sought to improve its own living standards rather than those of westerners. The public increasingly turned against European immigration. And the decline of North Sea oil continued apace.

So in this account the slow growth that followed the crash arose not from a failure of government policy (be it austerity in the left’s account; or excessive tax and regulation in the right’s), but from the exposure of demographic forces that were always present, and the passing of globalisation into a new phase that was not producing gains in living standards. And two further things were added after 2015: the decline of North Sea oil turned precipitate, and Brexit, after the referendum in 2016. Brexit has raised the cost of imports (especially if you attribute the depreciation of the pound that coincided with it, though I’m inclined to believe that much of this was in the pipeline anyway), made exporting harder, reduced the attractiveness of inward investment, and caused many immigrants to go home and made immigration harder. On that last point it is worth observing that the country has made up the shortfall in European immigrants with people from other countries, and in any case the European labour market is becoming tighter. But the labour market for immigrants became much less responsive to short-term demands. All round Brexit has added to the friction of running a business, rather than causing an immediate catastrophe.

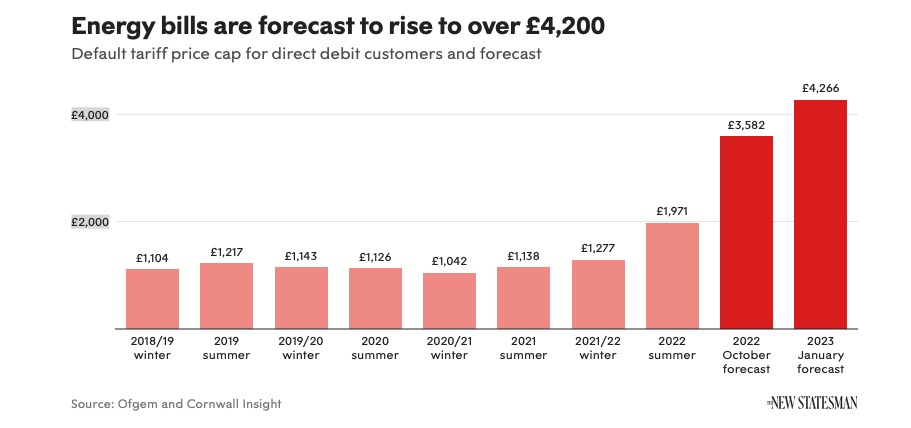

To these troubles we must now add two more. Firstly the gas and oil price spike, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, and secondly the rise in world interest rates. The energy price rise is a double whammy. It is helping to stoke up inflation, which causes economic damage in its own right, but also causes nominal interest rates to rise, which disrupts the economy in further ways; and the public expects the government to shield at least some of us, or even all of us, from the effects, causing a massive outlay in government spending. Rising interest rates make mortgages more expensive, which causes further hardship, and also disrupts a finance sector that has grown complacent on low interest rates.

The problem is this. Britain has a deep structural deficit in the trade of manufactured goods. We are heavily dependent on imports for our standard of living, and exports are nowhere near enough to cover this. We now have a substantial trade deficit on energy too, made worse by the Ukraine crisis. We still have a trade surplus on services, but nowhere near enough to cover the gap. Inward investment is sluggish, and anyway broader troubles in the world economy limit the possibilities. This means that the country as a whole has to borrow heavily from abroad – whether this is to fund the national debt or the private sector. Rising interest rates makes that more expensive. Crashing the pound would help exporters, maybe, and inward investment, almost certainly – and since nearly all the debt is denominated in sterling. would not make those debts any harder to maintain. But that would feed through to consumer prices, and destroy the economic strategy of the last few decades of consuming cheap imports.

There is a striking comparison to be made between Britain and Japan. Both are island nations with challenging demographics. Both have an uneasy relationship with their continental neighbours, on whom there is a degree of economic dependence. Japan has long set its face against immigration, an attitude that is prevailing Britain too. Japan has also been suffering economic stagnation, but it is not so obvious that the people living there mind, as economic wellbeing is spread widely. Something like Japan is what many of Britain’s Brexit supporters aspire to. But there is a crucial difference. Japan remains an industrial powerhouse, and produces a substantial trading surplus. They do not depend on inflows from abroad to keep the show on the road. That means the government has a huge amount of flexibility in borrowing money to meet its needs. Abacus economics is dead. It is living proof of the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) idea that the debate on government deficits and national debt is beside the point. Japan is in the position that Liz Truss seemed to think Britain was in when she promoted her tax-cutting and free-spending budget. But even under MMT consumption cannot outlast production forever, and inflation is admitted as a constraint. That is where Britain now is, and the government has little choice but to bring its budget position under control. The pressure is not extreme, as it has been for countries like Argentina or, in a rather different context, Greece in 2010 – but the trajectory needs to be clear or otherwise market interest rates will rise further than they otherwise would, with difficult repercussions.

That’s for now. But what should the country’s longer term strategy be? Ms Truss, and indeed Mr Sunak, subscribe to vision of what might be called a “buccaneer” strategy. They present a picture of the country being a haven for freewheeling businesses, attracted by low taxes and able to out-manoeuvre over-regulated competitors in Europe and elsewhere. But buccaneering has its dark side – the original buccaneers were licensed pirates, legal in their home domain and criminals elsewhere, after all. Britain would need to develop its already burgeoning function as a haven for grey and even darker money, from kleptocrats and criminals across the globe. The trick to this, as we have learned, is not so much lax laws on such things money laundering, but weak enforcement. Most Brexit supporters would likely connive at such a strategy, if not openly support it – on one condition: that public services are made more effective, and the state pension is improved – they are probably less fussed abut other aspects of welfare spending. This is where the main political battles are going to come in the next few years – as it is far from clear that such things can be maintained without increasing taxes.

Liberals recoil from such a strategy, but they will agree in principle to another strategic objective – that of energy security, and reducing the dependence on fossil fuel imports. There is a disagreement, of course, on whether that means developing the remaining domestic fossil-fuel opportunities. But, in principle at least, most can agree on the development of renewable energy, with the storage and grid upgrades that will be needed alongside it. One thing that helps is that this can largely be financed by foreign borrowing and equity investment – as the linkage of investment to financial returns is easy to make.

If liberals can agree on the need to turbo-charge the development of renewable energy, what alternative can they present to the buccaneer strategy? We can’t go back to being an industrial powerhouse with a strong export industry. That ship has sailed. We can make modest gains, but we can’t reverse more than half a century of decline.

I can’t see a single big idea, but a number of smaller ones might add up to a strategy. The drive for renewables should be tied to a more general mission to decarbonise the economy. This should drive a whole series of investments and reforms that will help renew life generally. The country should aim to ease trade with the European Union, which will mean accepting EU regulation in lots of areas. But we should be wary of relaxing immigration rules. The public seems to be happy with immigration by and large, if it is closely regulated. That means bureaucracy and friction, but in a democracy we have to work within the constraints of public consent. The government should also help develop industries where the country looks internationally competitive. Healthcare is the most promising area – I think the idea of cooperation between the NHS and private entrepreneurs to develop new treatments has much potential. The relatively unified state of health records is an opportunity, though bringing challenges with it. Also public services need to become more effective. That means shifting towards solving problems rather than simply repairing the damage after the event. This in turn means a stronger emphasis on prevention, and getting the various different services working together more closely. It is hard to see how this can work without more localised leadership and accountability – serious decentralisation and devolution. A further idea is political reform – through electoral reform, and reforming the House of Lords. This is as yet a bit of a long shot. For all public discontent about the state of politics, I see little groundswell for changing the system , as the was case in New Zealand in 1993, for example.

But we are going to have to get used to two two things alongside all of this. Taxes will need to rise, and economic growth will continue to be sluggish. This is the opposite to what Ms Truss was trying to achieve. That is not the end of the world. We can still achieve an improved quality of life and an environmentally sustainable way of being. That is a simple consequence of where the country stands as demographic forces assert themselves, and after the country’s mishandling of its industrial legacy over the generations.