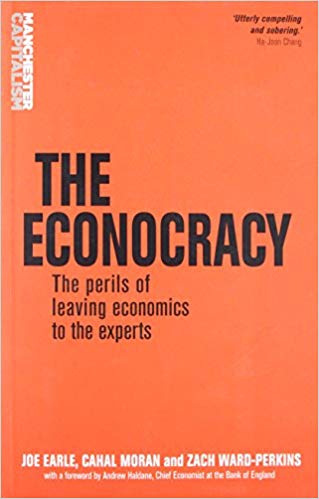

The Econocracy is a book written by three recent British economics graduates. It had quite a big initial impact, especially about the teaching of economics in universities. But although it rated a chapter in John McDonell’s recent book Economics for the Many, it looks as if not much is actually changing. Does that matter?

The scope of the book (which is quite short) is broad, combining specific complaints about university tuition with more fundamental issues for public policy. That is both a strength and a weakness. It helps draw people in, but it ends up being rather lightweight as a result. I have identified five main claims, and two main proposals. I will consider each in turn.

Claim 1: Public policy is controlled by a class of economic experts who shape policy choices in a way that is obscure to non-experts. This is the “Econocracy”. These experts try to frame political choices as a technical exercise which only they are capable of engaging in.

This is undoubtedly true. It is one reason that I decided to take an economics degree in 2005 after I left the City. If I was going to make headway in the field of public policy, as I hoped, then I had to master the internal language, and that was based on economics. All experts try to accrue power to themselves by making their field appear technical and mysterious, and this is what economists have succeeded in doing with public policy. But the public largely accepts this. The importance of jobs, pay and tax to our daily lives naturally gives space for experts who understand how these things fit together, or think they do. Making economics more transparent to the public, however, is easier said than done.

Claim 2: Economists operate according to a set of ideas, which should be open to challenge but are in fact a protected orthodoxy. The core of these ideas is what the authors call “neoclassical” economics, based on a holy trinity of individualism (people treated as independent economic agents), optimisation (these individuals act to maximise their welfare, or “utility”) and equilibrium (the interactions between agents settle down to a steady state which remains stable until external conditions change).

This is too shallow for me. The holy trinity of classical economics (and I don’t think the prefix “neo-” adds anything useful) leads to the use of relatively straightforward mathematical tools which can be used in a wide variety of contexts. Orthodox economists use these techniques far too much without question. In spite of what some claim to be a “physics envy”, theoretical economics are stuck in the economics equivalent of Newtonian mechanics, the first law of thermodynamics and Boyle’s law of gases for physics – what used to be O-level in my day. True physics envy would mean that they would be trying to push the boundaries out from this, by looking at non-equilibrium systems, for example. This looks much more realistic for financial markets and monetary policy, for example. Thus far I agree with the authors.

But orthodox economists are more open to challenge than the authors do not allow for. The most important way is through empirical studies of evidence, which takes up much, or even most, of the energies of modern economists. This has its own flaws. Classical economics underpins the theoretical predictions that are tested, and the assumption of IID (independent and identically distributed variables) is not challenged enough. But it does mean that modern orthodox economics is subject to a constant process of challenge that will eventually shift the theory and tackle awkward issues. For example there is now much study of inequality and the “left-behind” – areas that orthodox theoretical models tend to glass over. New approaches grounded on evidence do gain traction – like Thomas Piketty’s ideas on wealth distribution.

Meanwhile the authors seem to be too taken with what they consider to be alternatives to “neoclassical” theory. They list a series of rival theoretical approaches: three flavours of classical economics, Post-Keynesian, Marxist, Austrian, Feminist, and so on. This is a dangerous break from the idea of dialectical process, where new ideas should lead to challenge and synthesis, rather than a series of academics ploughing their own furrows. I can well understand the suspicion of mainstream economists that a lot of these schools are either obsolete (i.e. having been rolled into the modern synthesis) or attempts to bypass proper critical challenge. In the former case a bit like the first law of thermodynamics, and in the latter like climate change denial.

Claim 3: The economic conventional wisdom is rigidly enforced by universities who reject and suppress unorthodox approaches.

I find this very hard to offer a view on. There is a very strong system bias towards the mainstream, and in particular for research ratings and publication data. But how much are fresh ideas being suppressed, rather than flaky approaches (by which I mean people who are not open to their own ideas being challenged robustly) being denied oxygen? Every heterodox economist thinks they are being persecuted, but that by itself does not prove things one way or the other. Some social sciences have gone down the route a fluffy inclusiveness, where academics are allowed to publish their wacky ideas, but others don’t properly challenge them. Researchers submitting spoof papers can make a surprising amount of headway. It would be disastrous if economics went down that route.

Claim 4: Economics tuition is based on a narrow, hollowed out version of the orthodoxy, reduced to mathematical formulae and multiple choice questions. Students are not encouraged to think about their subject in a broader perspective. The current system of university finance encourages this narrow approach. Institutions must both protect their research status, which discourages heterodox approaches, and maximise student numbers while limiting costs, which pushes them towards the hollowed out approach to tuition.

Here the authors are on stronger ground, as they are able to draw on their direct experience as students. This criticism would not be fair of my course at UCL in 2005-2008. Lecturers were careful to relate the ideas they were teaching to the world outside, which was going through the early stages of the great financial crisis. And they did include a certain amount about rival ideas. There were gratuitous mathematics and graphs, especially in development economics, which I found irritating, however. (That may have cost me my first, as I struggled to play the game in my last year). But that was then: before the new university finance system was introduced. The authors paint a credible picture of how pressures on universities are reducing the quality of tuition. Beyond that I find it hard to comment.

Proposal 1: The authors want universities to adopt a more liberal approach to both the ideas and the way in which they are taught, and allow the “neoclassical” foundations to be challenged.

It is surely right on the face of things to support a more liberal approach. The problem is that the universities have responded to complaints with a new curriculum, which the authors reject, asthey still do not embrace heterodox theory. The universities’ reform efforts are being led by Professor Wendy Carlin from UCL. She was both my tutor when I was doing my degree, and the lecturer that I found the most valuable. She kept very close to the conventional theoretical models, but was very skilled, and rigorous, in applying them to the real world. Her criticisms of the Euro proved very apt. I naturally tend to sympathise with her side of the argument on this. I think that the authors are pointing to a fluffy inclusiveness rather than a proper liberal education which includes robust challenge. That may be unfair, but their list of alternatives to “neoclassical” theory does not inspire confidence. Still I think economics should push their curriculums to more essay type discussions, even if they are much harder to teach and mark.

Proposal 2: The authors also want to open up the public policy making process so that it is more accessible to the public and not dominated by obscure technical analysis.

In principle I agree with this, but it will be very, very hard. A lot of economics ideas are counter-intuitive. This is evidenced by a lot popular fallacies which economists rightly see through, such as the fallacy of composition (e.g. a national economy can be run like a household economy), the lump of labour (immigrants take away jobs…), and trade as a zero-sum game. Even trained economists can be led by their intuition into traps, as I think they are doing in most of their analysis of productivity, for example, though another version of the fallacy of composition. It is exactly these counter-intuitive insights that make the discipline so powerful. But they also make the analysis very hard to make accessible. Improving economics education will only make the economically literate a slightly less tiny minority.

It should be easier, however, to expose economic analysis to more widespread challenge from the experts themselves. And their needs to be a broader debate on how impacts of human wellbeing and the environment are accounted for when examining proposals. But much analysis is doomed to be both technical and obscure.

Conclusion

I find that this book disappoints, even as it makes a number of valuable points. Readers of this blog will know that I think there is much that is wrong with conventional economic analysis. But the authors fail to put their finger on where the problems really are, and what needs to be done.