A tale of two BBC TV dramas. My wife suggested that we watch two new series: The Responder and Rules of the Game, which had been well-reviewed. These dramas provide a telling contrast in the portrayal of character.

The Responder centres on a police officer in Liverpool, long past his sell-by date, and I have seen two episodes. The characters are dealt with sympathetically (mainly) and convincingly. This is gritty drama about manly working class people, and it is done well. Of course, it is not about typical working class life, but yet again deals with people working in the criminal justice, interfacing with the criminal underworld, and on the edge of violence. Well-trodden ground it may be, but it presents a sympathetic portrayal of a flawed character dealing with an unholy mess of life, and is one of many such dramas, made here in Britain and elsewhere too. We can all draw something from them.

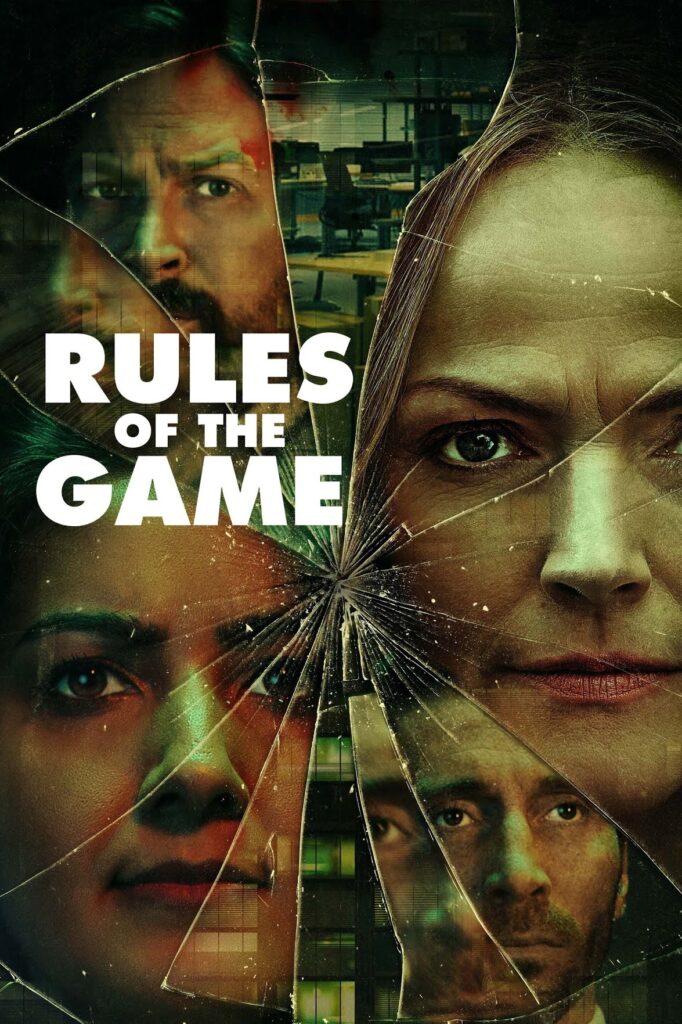

Rules of the Game is a different matter. I have seen the first episode, and that will be enough for me. It deals with an unfolding drama at a family-owned manufacturing business in some unspecified town north of London. The main characters are middle class and I quickly lost interest in all of them. They are cardboard cut-outs living lives of unrelenting falseness, devoid of loving, sympathetic relationships. This might be taken as satire, or a critique of middle class ways, or of capitalism perhaps. But it is actually trying to deal with a serious societal issue – abuse at the workplace – that really does merit serious treatment. But we were not going to be left with any penetrating insights on how these situations develop amongst real people.

On reflection this seems to be pretty typical of modern TV dramas. Most of them are just contrived nonsense stories as a pretext for showing violence on our screens in a variety of settings. Their favoured characters are flawed but honest working class (or perhaps more correctly, lower middle class) investigators trying to unravel a mystery in the face of unrelenting falseness from more senior management and officialdom. More serious dramas have many elements in common, but manage to be less contrived, offering glimpses into grittier parts of society. But even here middle class characters (or, perhaps, upper middle class ones – though all levels of social workers get the treatment too) are shown as unrelentingly false and devious, motivated by purely by money or status, or perhaps just unable to see beyond the rulebook. Of course falseness, money, status and compliance culture are genuine parts of the middle class world – but it is inhabited by real people, whose lives are much more complicated than typically shown. If drama can examine the dilemmas and flaws of a bent copper sympathetically, why can’t they do the same for the managing director of a business, or a chief constable, or even a social worker?

Perhaps the key to this is that these dramas (certainly the ones I watch) are made by middle class people for middle class people. Breaking through the middle class veneer gets us too close to home. Much easier if what we see on the box are caricatures and clearly not people like us, especially if it fits our prejudices about officialdom or people slightly higher up the chain of seniority.

We watch drama because it is not real life. We like to see a bit of violence; we love mysteries and whodunnits – which are mainly absent from our lives. But writers could try a lot harder with their middle class characters – especially when they have made such efforts with others.