It is very hard to think about anything other than Ukraine at the moment. What we are witnessing is a defining moment in European history – but one that is unresolved. Vladimir Putin has crossed a postwar red line in Europe by the use of warfare as a means of furthering political objectives. Military intervention has been not unknown in postwar Europe of course. The Soviet Union orchestrated a number of military interventions within the Communist Bloc. The collapse of Yugoslavia prompted a nasty war, in which European powers, and America, intervened. But the invasion of Ukraine feels very different. What to make of events so far?

A lot of what I wrote back in January stands the test of time. I suggested that Mr Putin wanted to achieve a rapid military victory over Ukraine; I questioned how easy that would be; and I said that an attack would galvanise a previously complacent Europe.

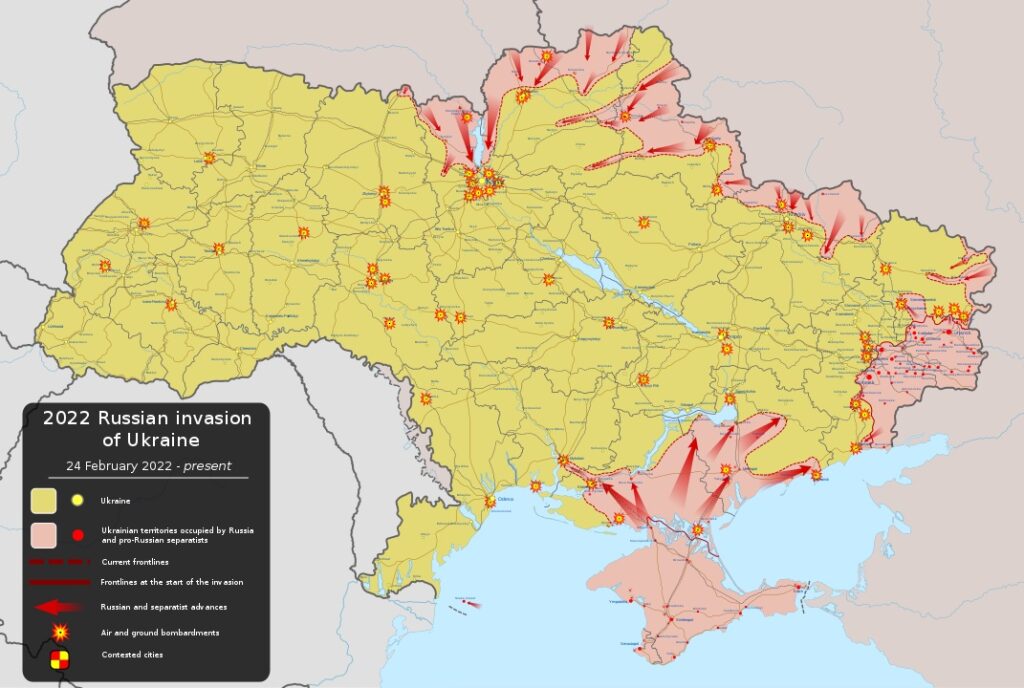

Clearly the Russian attack has not gone according to plan. Its leaders appear to have expected Ukrainian forces to collapse quickly. They seem to have believed their own propaganda that the Russian-speaking majority resented the current Ukrainian government as dominated by “fascists” from the west of the country, and that this would especially be the case in the east. Given that Russia has formidable intelligence services, with plenty of inside sources in Ukraine, this is an astonishing failure of intelligence. It is not hard to guess its cause though: Mr Putin’s advisers were too scared to tell him what he did not want to hear. It reminds me of the “groupthink” of George Bush’s regime prior to the 2003 Iraq War, which expected that the the Americans would be welcomed with open arms, and that a democratic state would be easy to impose. The Russian armed forces were clearly using the wrong tactics – not attacking with sufficient force at the critical points. They doubtless have been trying to avoid civilian casualties too, until today at least. We know from America’s experiences that this is an impossible promise to keep in a large-scale war, and Russia’s weapons are not as accurate – so the fact that there have been many civilian casualties does not disprove this.

One curiosity about all this is that Western military experts shared the Kremlin belief that Russian forces would achieve a rapid victory. The BBC calls the Russian military strength “overwhelming”. But it isn’t. In my January post I commented that I did not think the reported size of the Russian buildup of 100,000 men looked enough. Well, the latest estimates go up to 200,000, but that is still quite small force for such a big operation. Soviet-era armies were much, much bigger. What the experts appear to think is that Russia has modernised its armed forces on the US model, and have a corresponding level of effectiveness per man. If so then then that size of force would certainly be big enough to achieve a quick initial victory, and the problems would only start later on. But I don’t think that Russia’s modernisation has got that far. Or rather the theory has got ahead of the training and the actual technical capabilities. Furthermore there must be a question over the Russian forces’ morale. They were not psychologically prepared for a hard fight against people who look and speak the same as them. It is natural for military experts to overestimate their potential opponents as a matter of caution, especially as it helps make the case for more defence funding. I think that has happened here with Western military analysts.

Which is not to deny that the situation for Ukraine looks very grim. The ferocious bombardment of Kharkiv shows new Russian tactics. The conventional wisdom remains that Russia will prevail in the end. Personally, I do not take that for granted – but let us assume for now that this is right. What next? The problem for Russia is that the powerful resistance shown by Ukraine’s army, leaders and private citizens has established a creation myth for the Ukrainian nation. Mr Putin is right that originally the country was an artificial creation. But all nation-states are that at the beginning. National identity is forged by history, and Mr Putin’s hostility to Ukraine has helped forge that in double-quick time. This attack has sealed it. This will make any puppet state created in the country very hard to maintain. Internal security forces will have to be created from scratch in a short space of time, from unpromising raw materials; it will not be like Belarus. There is a risk of an insurgency. I honestly hope that, if Russia does win, that resistance will be only passive. The West should not support an insurgency. Having endured the horrors of the IRA campaign in the UK in the late 20th Century I wouldn’t wish that on anybody. But it is a risk.

But even if resistance is entirely passive, Russia will have to maintain a substantial security presence, reducing the level of threat elsewhere. It will also have a lot of wounds to lick. That gives NATO time to get its act together, if Mr Putin decides that is his next target. The key to that is Nato’s European members stepping up their military commitments. Mr Putin’s attack has certainly stimulated the European public in that direction. Also the promises made, when the eastern nations joined NATO, to limit eastern deployments can now be shredded. Unless there is regime change in Russia, we are headed towards a new cold war.

A further point of interest is developments have undermined Russia’s efforts to undermine Western politics, through the spread of disinformation and sponsoring disruptive politicians. In the period leading up to the attack there quite a number of apologists for Mr Putin. On the right were those, like Donald Trump, who are fascinated by the exercise of raw power. People on the left like anything that challenges US hegemony: we had the rather incongruous spectacle of people who claim high political principle with respect to the Iraq wars and Palestine coming over as hardened exponents of realpolitik. But the narrative now offered by mainstream media is a compelling one, and Russia has offered no coherent alternative (or not outside its own borders – within them they can promote a version of events that is much further from reality). For people the right there is the spectacle of people bravely defending against a sophisticated army using citizen militias, an idea they love. On the left, Russian apologists have been led up the garden path by Russian claims that they were not going to attack, as well ass claims that the Ukrainian regime did not have wide public support, and made to look very foolish. Anti-Russian sentiment has exploded. This has given tough sanctions against Russia an easy ride. This may have been more than Russia expected. The Russian disinformation campaign is now wholly out its depth.

Meanwhile the US President Joe Biden has played a very well-judged game. He opted to share intelligence early and quickly about Russian intentions. This pressurised Russia, forcing it into repeated denials that have weakened its overall standing – and readying the public at large for what was about to happen. He also made very clear what his response would be, again preparing the ground well. If the Russians are surprised by the strength of the sanctions, they have no reason to be.

Overall the impression is that Mr Putin became overconfident, both based on his past successes, and the apparent weakness of the West. He suffered from the delusion of many authoritarians that the Western public is too focused on the comfortable life to be any good at the life-and-death stuff. But when provoked the public responds. This now means that the Russian state has many problems crowding in on all sides: from the conduct of the war, to response to sanctions, to managing public opinion to even fending off cyber attacks (although as yet not particularly serious ones). Mr Putin’s references to his nuclear arsenal is a sign of weakness. But Mr Putin has invested a lot in that arsenal, and he wants it to count for something.

That leaves us in a very uncomfortable place. Mr Putin will be desperate not to lose face. Things have to get worse before there is much hope of them getting better. Hopes of an early end to the pain depend on Mr Putin being overthrown. And the chances of that are unknowable.