The picture shows my rubbish bin last Thursday, our normal collection day. It had four weeks of rubbish in it, and was put out more in hope than expectation that it would be collected by the limited service in operation. It wasn’t. Our bin men have been on strike for a month, with no sign of a settlement in sight. It is just one facet of the inflation crisis that is engulfing Britain, and much of the rest of the world too. It has now reached the top of the political agenda. But just what can, and should, politicians do?

When I last posted on this, I contrasted two forms of inflation. One is a degradation in the value of the currency – the process of the prices of things generally going up, without relative prices between different things changing (and especially between consumer prices and wages). The other is a process of the economy reaching a new reality, typically because supply difficulties are reducing the standard of living. If the supply of oil, for example, is substantially reduced, and its price rises as a result, we have to consume less. Assuming that there are no cheap substitutes, then there is nothing that will stop society being poorer. How society should respond to either sort of inflation is different. In principle, the first can be stopped by processes of economic management (though whether it should be, or at what level, is another matter). Responding to the second sort is a question of distributing the pain – nothing will stop us being poorer, in the short term at least. Of course the second sort of inflation often leads to the first – if people respond by trying to avoid pain altogether by raising wages and benefits across the board. That is how the inflation crisis of the 1970s got going.

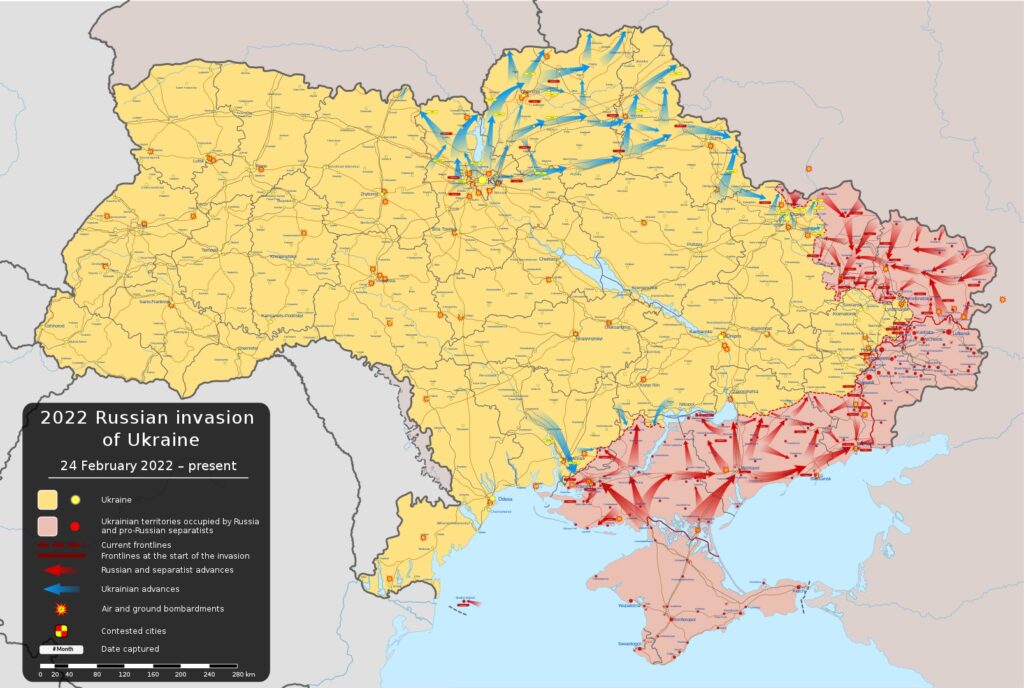

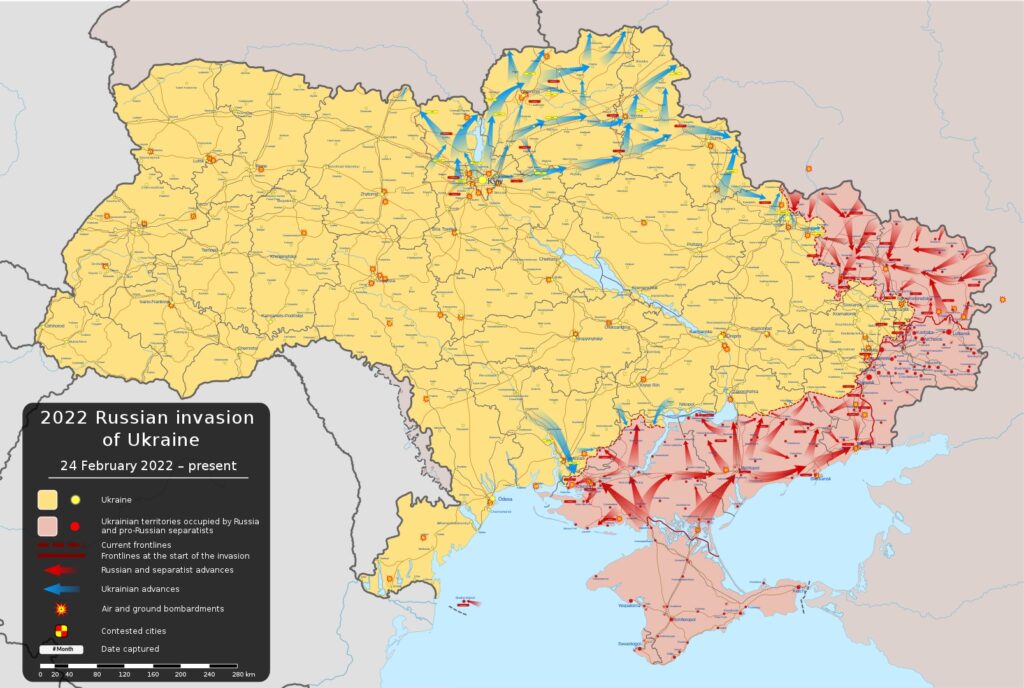

The inflation that is hitting Britain is mainly the second sort – prices rising as a matter of economic adjustment. This is driven mainly by three things: increased trading and labour costs as a result of Brexit (counting changed immigration patterns as part of that process, and the reduced availability of cheap labour – though some of that may well have happened without Brexit); the disruption of supply chains following the covid pandemic; and the war in Ukraine, and especially its impact on hydrocarbons, to be followed by its impact on foodstuffs. In the short term the question for public policy is how the pain can be shared equitably. Trying to escape the pain through increased wages and government handouts will simply stoke up the second sort of inflation.

This is not easy territory to pick through for public policy. The first question is whether inflation is an evil at all, or when. Many economists don’t feel that it should be, up to a point. Inflation makes it easier to make adjustments to relative prices (and especially reducing wages compared to consumer prices), and it also allows the possibility of negative real interest rates, reducing the possibility of a zero-bound trap. This idea weighs heavily on theoretical macroeconomists – the idea being that the lower limit on nominal interest rates is zero – which means that it is possible that interest rates can’t be eased when they should be – causing a recession. When I was an economics student in the mid-noughties I read lengthy discussions led by liberal economists such as Paul Krugman suggesting that Japan was caught in just such a trap and that it should implement radical policies to raise its inflation rate (some of mr Krugman’s ideas on how to do this were quite barmy). I have never been comfortable with this. The public does not share this equanimity with regard to inflation. To them the currency is a sacred bond of trust between the citizen and the government. The citizen trusts their savings to the financial system so that they can be used for investment; the government ensures that the currency maintains its value so that the citizen can spend the money later. Inflation is theft by complacent ruling elites – a transfer of wealth from honest savers to devious borrowers. Liberal economists tend to completely underestimate this sentiment, and the idea that inflation corrodes trust in the system of government. The popularity of the euro, for example, in France and Italy is reflection of this. Populist politicians who seek to take their countries out of the euro find that it is a sort of political third rail. Marine Le Pen and Matteo Salvini have both been frazzled on this. Liberal economists tend to think that the euro is an affront to sensible economic management, but to many it has restored their faith in money and civic governance.

So politicians need to take inflation seriously. But that leaves a conundrum. The two main methods of squeezing it out of the system are also unpopular. The first is holding back wages. That stops prices spiralling, allowing inflationary shocks to work their way through quickly. The second is raising interest rates. This should reduce borrowing and investment, deflating the economy and reducing the pressure on both consumer prices and wages. Raising interest rates can be popular with a certain class of conservative savers – but it also tends to dent property prices and cause unemployment, which give a sense of economic mismanagement. A third method of dealing with inflation is less talked of: increasing taxes to reduce the level of consumption. This faces some fairly obvious problems when used on consumption taxes such as VAT – as it just raises prices further; income taxes are more equitable, but hardly a popular alternative.

The British government has some things going for it when it comes to overcoming the inflation surge. The first is that wages are so far lagging consumer prices: by 7% compared to 9%. Moreover a lot of the 7% reflects one-off bonuses. The second thing is that tax rises are crimping people on middle and higher incomes, which in principle should reduce demand. National Insurance rates have gone up and the threshold for higher rate tax has been frozen, creating a fiscal drag effect. This should give the government some scope for alleviating hardship without raising demand excessively. There are three things the government needs to think about doing.

The first is raising benefits for the least well off. The inflation adjustments made to benefits was based on numbers prior to the main surge, and so are inadequate to meed the increased energy and food costs, never mind all the other costs that are going up. The most obvious thing to do is to raise Universal Credit, for which there is a precedent during the covid crisis. This would be costly, but it would also be the best targeted measure that they could devise. There are other benefits complementary to UC, which, apparently, are technically harder to increase. But it is hard to take this seriously as a reason not to act. The basic state pension is also another place to look. The government, however, is very reluctant to commit to serious increases here. The reason may be political – the recipients of these benefits are unlikely to be Conservative supporters (except the state pension). Instead the government has been looking at other benefits, and committing much less money than these measures would require. The rumours are that something is in the works.

The second issue is public sector pay. According to the ONS this has been increasing at the rate of only 1.2%. The government has raised the minimum wage by 6.6%, but otherwise is wants to keep public sector wages down. This would certainly serve to keep demand pegged – but just how realistic is it? My bin men aren’t the first to go on strike – and neighbouring local authorities have been forced to pay a lot more than they had planned. And they are still on strike after being offered an increase this year of “up to 17%” and parity with workers from neighbouring councils. Rail strikes are threatened. There is a staffing crisis in the NHS. If private sector pay is allowed to shoot ahead of that in public sector, there will be recruitment and retention issues. It is not hard to see serious trouble ahead.

The third issue is levying a windfall tax on oil and gas producers, who are making massive profits, and maybe other energy providers too. Economically this is something of a sideshow. A tax would not affect levels of consumption in the economy by much at all. Still, it is useful political theatre and reduces the pressure on national debt – though just how important this is remains hotly debated. The government is reluctant to do this, though the reasons offered look pretty weak – at least as far as the major public companies are concerned. Apparently the government is now trying to link such a tax to levels of investment. That is a theoretically sensible approach, but hard in practice.

Meanwhile the government, and many of its MPs, hope that they can cut income tax before the next general election, likely to in the autumn of 2023, or the following spring. This looks like a neoliberal delusion – a failure to understand the inevitable rise in the scale of government spending in the face of demographic and other pressures. Still, that delusion still seems to have powerful followers.

But the real hot potato is wages. Inflation the moment is primarily caused by supply disruptions that make us poorer. The more we try to keep levels of pay rising at the same pace as consumer prices, the longer the inflation crisis will persist. The biggest headache is in the private sector. The government has little influence over this, but the more pay rises there, the worse the pressure will be on the public sector. This is shaped by the zeitgeist. And here the narrative from the government – and other politicians – is muddled. There are no grave messages that the country is being hit hard by a number of things outside its control, and that we must grit our teeth to get through it. Instead the government wants to portray the economy as in fine fettle, and also that we should expect wages to rise as we move to high-wage high-productivity post-Brexit economy. Government politicians don’t want to admit that the economy is in fact in trouble. The opposition wants to suggest that it is all the result of incompetence that can be put right quickly with a transfer of power. They doubtless hope that the pressures will have eased by the time this transfer takes place.

So my guess is that inflation will persist. Public sector strikes will multiply, and interest rates will start to rise much more rapidly that the mainly token changes we have seen so far. Avoiding this will require strong political leadership of the type we are unlikely to get from anywhere.