The Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer, is taking a lot of criticism. A minority view, promoted by Matt Goodwin, is that he is about to unleash a wave of woke nonsense on the British public, after Labour win the next election. A more widely publicised view is that he is so desperate to win the election that he has completely hollowed out a potentially radical Labour programme, and so stands for little or nothing. Both critiques miss the mark.

Mr Goodwin is showing how complete is his transition from a sympathetic but objective observer to the rise of the populist right, to being an active s**t stirrer, mixing in populist nonsense with his often trenchant analysis. This particular line of argument has been lifted from the American right but sits awkwardly with the facts of British public life. The American left, with its adoption of identity politics and much other nonsense, can be pretty scary. And they have their admirers in Britain, and these doubtless include many people who would be put in positions of influence by a Labour government. But the political mood is clearly against it, and Mr Starmer will be very sensitive to this once in power. Expect some nonsense around the fringes, hyped up like mad by right-wing media, but little that affects most people’s daily lives.

But what of the idea that Mr Starmer has so hollowed-out Labour’s policy platform that there is little worthwhile left? It is true that he is trying to steer clear of radicalism – but radicalism is something favoured by political activists and not the public at large. Lack of radicalism is a feature, not a fault. Rather what Mr Starmer wants to stand for is calm confidence – something the Conservatives have failed to achieve since Brexit, with some half-hearted resistance from two of their leaders, Rishi Sunak and Theresa May. But is there a deeper policy programme too? The place to start looking is Labour’s five missions – something Mr Starmer pushes relentlessly, but which is largely ignored by journalists.

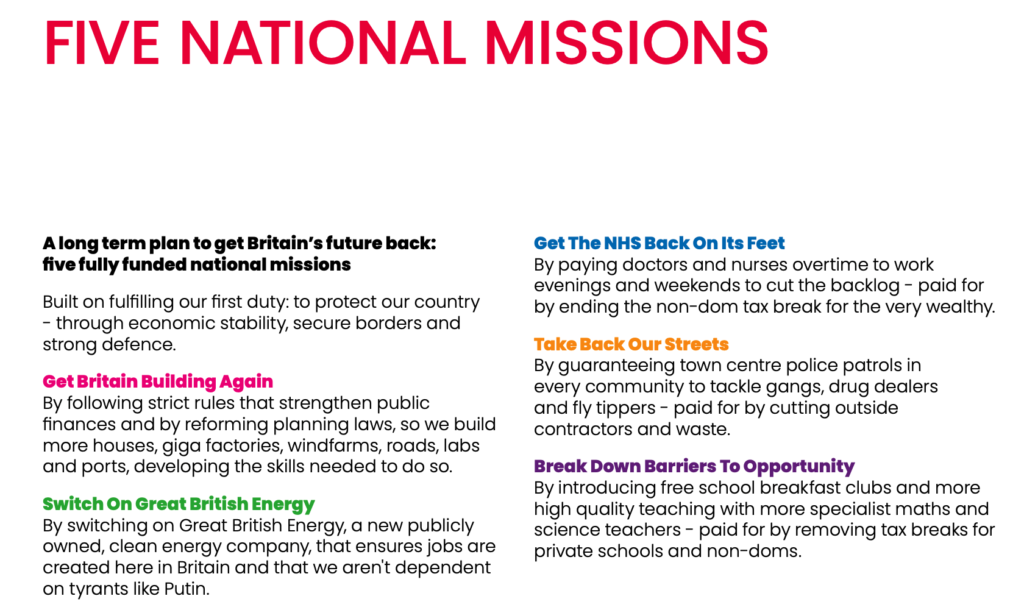

What are the five missions? This is from the party’s website (though since withdrawn, doubtless because of its reference to the taxing of non-doms):

It is tempting to dismiss this as political guff. Firstly, it is more than five areas of policy focus – because the five missions come on top of the three “foundations” of economic stability, secure borders and strong defence – though to be fair these three areas are points of consensus between them and the Conservatives, at least in theory. Missions 3, 4 and 5 are underwhelming. They are limited by having to tie them to new taxes or waste reduction, where opportunities are limited and gimmicky; the non-dom tax has also been pre-empted by the Conservatives. The headline promises don’t begin to tackle the deep-seated problems with the NHS, law enforcement and education. The second mission is mysterious; a new energy company doesn’t do anything of itself – it’s what that company does that will make a difference. This isn’t much clearer when clicking through to the detail behind it. This promises an ambitious overhaul of the country’s infrastructure towards renewables, but with few specifics and no talk of costs. This makes somewhat more sense when tied to the much publicised £28bn a year investment programme, which was live when the Five Missions were first announced, but which has been scaled back since. Still, this mission does have one of the most senior members of the shadow cabinet behind it – Ed Miliband, the former party leader, who was energy minister in the last Labour government. As an organising principle of the next government this clearly represents progress from the half-hearted approach of the current government – who want to rest on the laurels of their achievements when pushed by the Lib Dems in the coalition years. Still, this is a difference of emphasis rather than overall strategy.

It is the first mission that is the most telling – and especially the promise to change planning rules. It is one of the very few areas where Sir Keir is happy to challenge floating voters – in contrast to the Conservatives, and even the Lib Dems, who seem in thrall to local NIMBYs. This makes a degree of sense, since Labour draws most of its strength from urban areas and people who rent their homes – who generally aren’t NIMBYs. It still looks quite brave, as strategically Labour need to keep pressure up on the “Blue Wall” of commuter seats. Alas there is almost no detail on the Labour website about how the party plans to approach this. If you click through, it is mostly whinging about Tory failure and wittering on about economic growth – pretty much political boilerplate. They talk of building 1.5 million homes (presumably 300,000 a year – the same as the Conservatives promised at the last election), and first time buyers “getting first dibs”. But it looks as if Labour in government could be quite brave here – and if they are, it could make a real difference. But it will only work if they break away from the developer-led model of house building that has dominated the last forty years or so of housing policy. Developers are too interested in realising profits on their land banks to do anything at pace. Labour will also have to work out how to expand the capacity of Britain’s construction industry. The Conservatives have failed in spite of much talk because these things are politically challenging. But if Labour frame their policy in terms of meeting the housing needs of working people and families then I suspect that the political costs will be manageable. I live in an area where NIMBYism is deeply embedded – but even here people admit that more houses need to be built. But it remains very easy to criticise current plans as being the wrong sort of houses in the wrong places – Labour needs to tackle this criticism head-on.

So Sir Keir is clearly signalling that tackling the housing shortage and transforming the country’s energy infrastructure will be points of focus. He is a managerial sort of person – so if he defines these objectives clearly he will follow them. This is in stark contrast to Boris Johnson, the prime minister in 2019, who was all bluff and not a serious programme manager. He set targets but wasted little thought on how they might be achieved. If Sir Keir’s government makes headway on overhauling the country’s energy infrastructure and addressing housing shortages, then it will be very consequential.

But the real problem for any objective assessment of Labour’s programme is that we have little idea about how it will tackle the quad of challenges of taxes, inflation, public services and immigration. These four issues will surely dominate the next government’s agenda, as they have for this one. Progress on each one of these four will undermine the other three. For example, if the government takes a strict line on immigration, in line with public opinion, and to help ease the housing crisis (provided that workers can be found in construction), then inflationary pressure will rise as lower skilled workers are paid more – after all that is one of the reasons given for lower immigration levels. Inflation leads to cost of living pressures and higher nominal interest rates – which raises the cost of mortgages which are already stretching people. To damp this down would require higher taxes and/or reduced spending on public services. Of course these dilemmas would ease if productivity-led economic growth increased the economy’s capacity – but productivity gains are liable to be lost in the headwinds of demographic change, the de-globalisation of trade and the increasing weight of the service economy.

But the Conservatives don’t have any answers to this quad either – so they will not place Labour under any serious pressure until they are in opposition, when magical thinking becomes a possibility again. The political parties are not being held to account. M

Meanwhile Sir Keir’s five missions give us a hint about the other priorities of a Labour government.