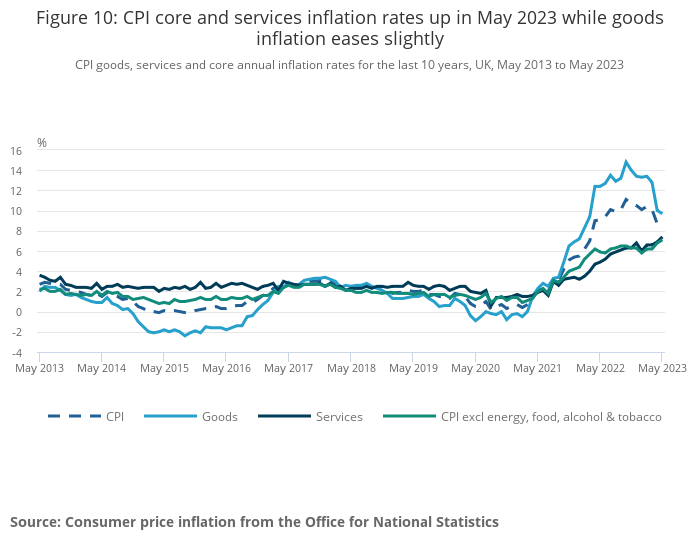

Yesterday Britain’s state statistical agency, the Office for National Statistics, released inflation figures for May 2023. The headline figure of 8.3% was unchanged from April, but the “underlying” rate (CPI excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco in the above chart) continued to rise. Commentary on the BBC Today programme and in today’s Financial Times was notably dark. There seemed general agreement that the Bank of England would have to increase interest rates, and keep them higher for longer than previously expected. And indeed the Bank raised rates by a full 0.5% later in the day; 0.25% had been widely expected.

Until now two overlapping narratives about inflation had been prevalent among the commentariat. The first, call it “global shock” is that the rise in inflation since 2021 has been essentially a temporary one – driven by higher oil and gas prices, and exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, which affect all developed economies. The thinking was that these would either reverse or get baked in (i.e., drop out of the 12 month statistics). When the prime minister Rishi Sunak set out his five main priorities at the start of this year, halving the rate of inflation came top. The general view at the time was that this target would be achieved without any government action so that the Mr Sunak could take credit for a statistical artefact. While it was popular to criticise central bankers for thinking that inflation would be “transitory” when it first started to rise, it hasn’t stopped many people from thinking that themselves subconsciously. The second narrative, “supply shock”, was a bit more subtle: it was that inflation this time was a supply-side phenomenon and not resulting from excessive demand. The upshot is that the solution is not to crimp demand by raising interest rates, but to wait for the supply side of the economy to correct – indeed raising rates would only reduce the investment needed to fix the problem. The supply side issues referred to included the energy crunch, but also the repercussions of the covid-19 pandemic on supply chains.

These narratives are breaking down, especially as the rate of price increases in services persists. This seems directly related to rising levels of pay, which have also come through in the statistics. While some academics suggest that the “wage-price spiral” of 1970s fame is no longer a major dynamic (see here in The Economist), there seems to be what The FT’s Chris Giles calls a “ratchet”. Pay rates increase in response to energy prices, and this feeds into service costs, which in turn might lead into further payrises. Meanwhile supply side issues do not seem to be sorting themselves out; labour shortages are ongoing. This seems to be particularly strong in the UK. Various things catch the blame for this: EU nationals going home after Brexit; lack of flexibility in the post-Brexit immigration system; more chronic illness; people retiring earlier than expected: take your pick. What is now clear is that if inflation is to be limited something has to be done to limit demand.

At this point the economic illiteracy of the political class becomes evident. Many hang on to the idea that responsibility for managing inflation rests with the Bank of England alone. Some seem to believe that this can be done in some kind of immaculate way without hurting economic growth, or at any rate that there was an opportunity to do this if the Bank had reacted to initial energy price shock sooner. The previous Prime Minister, Liz Truss, seems to have held this view, and now a number of government advisers are briefing the press along these lines. In fact the Bank was following a firm consensus shared by the government, and the political stink that would have arisen if it had tried would have been a sight to behold, with the “global shock” and “supply shock” narratives being widely trumpeted. Now at least people are understanding that “if it isn’t hurting, it isn’t working”, an idea that was widespread dung the last inflation crisis in the 1990s. And yet the hurting seems to be concentrated on one particular group: home-owners with mortgages. Well there are others: public sector workers, where the government is fighting hard to limit payrises, and people living in rented accommodation, as rents are on the rise (although the reasons for the rental problems seem to be complex, with interest rates only one factor). Many others, such as people who own their homes with mortgage paid off (like me) are under no special pressure. All this does not seem to be especially fair.

The political debate around this is laughable. Labour’s priority is to try and blame the crisis on the Conservatives. And yet they cannot point to a clear “told-you-so” moment to show how they might have done anything differently. Neither are their ideas on tackling the crisis now conspicuously different. They give the impression that they would be easier on public sector pay, but not how they would manage the fiscal consequences of this. Their very limited tax raising ideas to cover extra spending would do nothing to manage demand in the economy. The Lib Dems suggest a hardship fund to help the most pressurised home-owners; this is not as mad as the thoughts of some Tory backbenchers to offer tax relief to all people with mortgages – but would still need to be balanced with a tax rise that hurts demand, which various forms of tax on excess profits would not. Supporters of Liz Truss would focus more clearly on various supply-side problems, like the need to build more housing, but wreck this with their advocacy of lower taxes. Instead of this hot air, two particular ideas should be current in political circles.

The first is that we could manage the demand side of the economy more fairly through raising taxes. By this I don’t mean the various tax gimmicks that opposition parties try out which could raise funds without hurting most people (windfall taxes, taxing rich people’s perks, non-doms, and so on) – as the “if it’s not hurting, it’s not working” mantra applies here too. It means putting up taxes on the big three – income tax, VAT or National Insurance. In practice, that means income tax. National Insurance lets rich pensioners off; VAT is too hard to explain when trying to fight price raises, at its short-term effect is to increase inflation. To be fair, the government is raising income tax by refusing to raise allowances and thresholds, causing “fiscal drag”, though they don’t want to draw attention to this. But more needs to be done – and if it was, there would be less pressure on interest rates.

The second idea is to suggest that inflation might not be such a bad thing after all, if it means a rebalancing of pay to those currently earning less. This would flow from policies to limit immigration of lower-skilled workers, for example. The corollary of this would be to temporarily raise the Bank’s inflation target, and to find ways of cracking down on profiteering by businesses (so that the benefits of laxity went to the workers, not business owners). That, incidentally, is a bit harder than it might seem, as one of the side-effects of inflation is to create false profits from the time lag between paying for inputs and billing for outputs. That would be a distinctly socialist approach, but surely no madder making mortgage holders bear the brunt of the fight against inflation. A bit of dialectical debate around this idea, and that of tax rises, would do no harm. But both are politically toxic.

High inflation, and increasing hardship for a growing number of people, is the result of multiple problems in the British economy. Strong political leadership will be needed if the outcome is to be a fairer society – which it could be. Alas no such leadership is in sight.