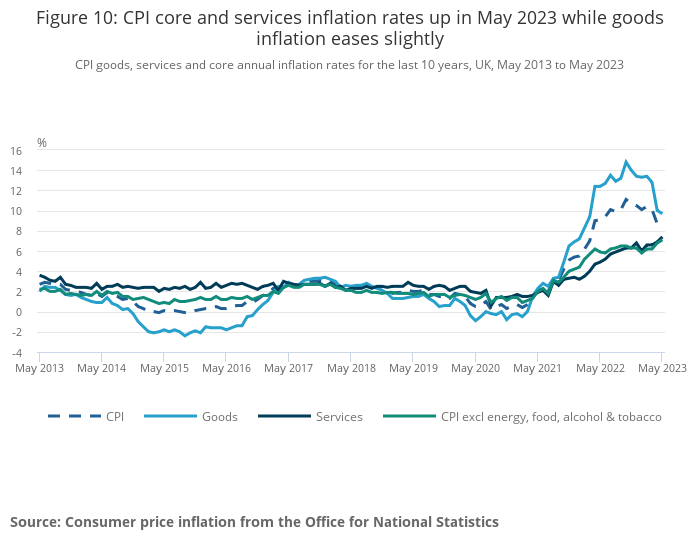

Yesterday Britain’s state statistical agency, the Office for National Statistics, released inflation figures for May 2023. The headline figure of 8.3% was unchanged from April, but the “underlying” rate (CPI excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco in the above chart) continued to rise. Commentary on the BBC Today programme and in today’s Financial Times was notably dark. There seemed general agreement that the Bank of England would have to increase interest rates, and keep them higher for longer than previously expected. And indeed the Bank raised rates by a full 0.5% later in the day; 0.25% had been widely expected.

Until now two overlapping narratives about inflation had been prevalent among the commentariat. The first, call it “global shock” is that the rise in inflation since 2021 has been essentially a temporary one – driven by higher oil and gas prices, and exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, which affect all developed economies. The thinking was that these would either reverse or get baked in (i.e., drop out of the 12 month statistics). When the prime minister Rishi Sunak set out his five main priorities at the start of this year, halving the rate of inflation came top. The general view at the time was that this target would be achieved without any government action so that the Mr Sunak could take credit for a statistical artefact. While it was popular to criticise central bankers for thinking that inflation would be “transitory” when it first started to rise, it hasn’t stopped many people from thinking that themselves subconsciously. The second narrative, “supply shock”, was a bit more subtle: it was that inflation this time was a supply-side phenomenon and not resulting from excessive demand. The upshot is that the solution is not to crimp demand by raising interest rates, but to wait for the supply side of the economy to correct – indeed raising rates would only reduce the investment needed to fix the problem. The supply side issues referred to included the energy crunch, but also the repercussions of the covid-19 pandemic on supply chains.

These narratives are breaking down, especially as the rate of price increases in services persists. This seems directly related to rising levels of pay, which have also come through in the statistics. While some academics suggest that the “wage-price spiral” of 1970s fame is no longer a major dynamic (see here in The Economist), there seems to be what The FT’s Chris Giles calls a “ratchet”. Pay rates increase in response to energy prices, and this feeds into service costs, which in turn might lead into further payrises. Meanwhile supply side issues do not seem to be sorting themselves out; labour shortages are ongoing. This seems to be particularly strong in the UK. Various things catch the blame for this: EU nationals going home after Brexit; lack of flexibility in the post-Brexit immigration system; more chronic illness; people retiring earlier than expected: take your pick. What is now clear is that if inflation is to be limited something has to be done to limit demand.

At this point the economic illiteracy of the political class becomes evident. Many hang on to the idea that responsibility for managing inflation rests with the Bank of England alone. Some seem to believe that this can be done in some kind of immaculate way without hurting economic growth, or at any rate that there was an opportunity to do this if the Bank had reacted to initial energy price shock sooner. The previous Prime Minister, Liz Truss, seems to have held this view, and now a number of government advisers are briefing the press along these lines. In fact the Bank was following a firm consensus shared by the government, and the political stink that would have arisen if it had tried would have been a sight to behold, with the “global shock” and “supply shock” narratives being widely trumpeted. Now at least people are understanding that “if it isn’t hurting, it isn’t working”, an idea that was widespread dung the last inflation crisis in the 1990s. And yet the hurting seems to be concentrated on one particular group: home-owners with mortgages. Well there are others: public sector workers, where the government is fighting hard to limit payrises, and people living in rented accommodation, as rents are on the rise (although the reasons for the rental problems seem to be complex, with interest rates only one factor). Many others, such as people who own their homes with mortgage paid off (like me) are under no special pressure. All this does not seem to be especially fair.

The political debate around this is laughable. Labour’s priority is to try and blame the crisis on the Conservatives. And yet they cannot point to a clear “told-you-so” moment to show how they might have done anything differently. Neither are their ideas on tackling the crisis now conspicuously different. They give the impression that they would be easier on public sector pay, but not how they would manage the fiscal consequences of this. Their very limited tax raising ideas to cover extra spending would do nothing to manage demand in the economy. The Lib Dems suggest a hardship fund to help the most pressurised home-owners; this is not as mad as the thoughts of some Tory backbenchers to offer tax relief to all people with mortgages – but would still need to be balanced with a tax rise that hurts demand, which various forms of tax on excess profits would not. Supporters of Liz Truss would focus more clearly on various supply-side problems, like the need to build more housing, but wreck this with their advocacy of lower taxes. Instead of this hot air, two particular ideas should be current in political circles.

The first is that we could manage the demand side of the economy more fairly through raising taxes. By this I don’t mean the various tax gimmicks that opposition parties try out which could raise funds without hurting most people (windfall taxes, taxing rich people’s perks, non-doms, and so on) – as the “if it’s not hurting, it’s not working” mantra applies here too. It means putting up taxes on the big three – income tax, VAT or National Insurance. In practice, that means income tax. National Insurance lets rich pensioners off; VAT is too hard to explain when trying to fight price raises, at its short-term effect is to increase inflation. To be fair, the government is raising income tax by refusing to raise allowances and thresholds, causing “fiscal drag”, though they don’t want to draw attention to this. But more needs to be done – and if it was, there would be less pressure on interest rates.

The second idea is to suggest that inflation might not be such a bad thing after all, if it means a rebalancing of pay to those currently earning less. This would flow from policies to limit immigration of lower-skilled workers, for example. The corollary of this would be to temporarily raise the Bank’s inflation target, and to find ways of cracking down on profiteering by businesses (so that the benefits of laxity went to the workers, not business owners). That, incidentally, is a bit harder than it might seem, as one of the side-effects of inflation is to create false profits from the time lag between paying for inputs and billing for outputs. That would be a distinctly socialist approach, but surely no madder making mortgage holders bear the brunt of the fight against inflation. A bit of dialectical debate around this idea, and that of tax rises, would do no harm. But both are politically toxic.

High inflation, and increasing hardship for a growing number of people, is the result of multiple problems in the British economy. Strong political leadership will be needed if the outcome is to be a fairer society – which it could be. Alas no such leadership is in sight.

You’re right that there is no easy solution, but we have to start by trying to explain why the present policy of relying on increases in interest rates, which is essentially the new monetarism, is probably the worst of all solutions to the extent that it can be argued that it is no solution at all.

Many monetarists, including for example Rachel Reeves, are concerned about the effects of their policy, and so want to ameliorate it. They want to force banks to allow borrowers to extend their loan periods or even to switch to interest-only payments on their mortgages. They will probably offer this of their own volition if the alternative is a default. At best this could be regarded as a ‘sticking plaster’ type solution. In reality it means less money is repaid. There will be more money left in the economy – so reducing the impact of monetary policy. The supposedly ‘independent’ central bank then has to raise interest rates even higher than previously.

So the question arises if the ‘stickingplaster-ists’ really understand their own economic ideology? It is worrying if they don’t because it is necessary to first understand an existing theory to also understand where its flaws might lie.

The first, and most obvious, flaw is in thinking the central bank can ever be independent. The BoE is owned by the Government and is essentially a part of government. Did they really decide to buy up £700 bn or so of bonds as part of the QE program on their own initiative thinking it might be a good idea? I don’t think so!

So the main problem has to be with government in pretending that it’s down to the BoE to control inflation to meet a 2% target. All it can do, to try to control inflation, is raise interest rates and it can only do this because New Labour handed over the power to do so in 1997.

All economists would agree that government spending more into the economy is reflationary, and potentially inflationary. Somehow the monetarists have convinced themselves that Government spending more into the economy in the form of increased interest rates is an exception to this rule. Looked at another way, increased interest rates increase business costs, and so cause more inflation in the short term. This can be seen particularly in the rental market. So, when this doesn’t work, the BoE increases rates some more. When it doesn’t work yet again….

It’s all the central bank can do. The US Fed and the ECB are doing the same thing so its not just a British problem.

In the end something has to give, the economy crashes and we have a recession with lower inflation because no one is spending very much rather than the amount of money in the economy being diminished. So we’ll probably have a crash all over again – maybe even as bad as we saw in 2008. We first saw this happen when Margaret Thatcher raised interest rates sharply after her 1979 election victory. We had a crash in the early 80s. The same thing happened a decade later after the Lawson boom of the late 80’s and then the crash of the early 90s. There was the ‘tech wreck’ at the turn of the millenium which led to the events of 2008.

So we are probably due another crash if we accept that these events are out of our control. There really isn’t any need to do this if we accept that creating ever higher levels of private debt isn’t the best way to reflate an economy. Later, when we might need to deflate it, neither is turning that high level into a high level of bad private debt.

I agree with a lot of this. Government can’t abdicate responsibility for any aspect of the economy, including management of inflation – or financial regulation. Gordon Brown’s tripartite division of responsibilities proved to be a disaster. However there are arguments for keeping the interest rate decision at arm’s length. The reason why monetarism originally gained traction was that its supporters (fiscal conservatives) felt that it would keep government budgets in check, as there would be no reason to use budget deficits to manage the macro economy. That has gone badly – with the Bush and Trummp tax cuts, and massive spending on the pandemic, for example. I think people look back at the record of the Bundesbank in the 1970s as an exemplar. but a huge amount of nonsense is talked about central banks setting inflation expectations. As to question of whether raising interest rates is itself inflationary, I think quite a bit of thinking has been done on this, with a consensus that inflationary effects are trumped by disincentives to borrow and improved incentives to save. But in the end this amounts to the policy working by threatening catastrophe on the economy, which is no way to run a mature polity.

Our politicians (not just in the UK) seem completely out of their depth – but then I think the same can be said for most economic policy professionals.

@ Matthew,

It is interesting that you say “….there would be no reason to use budget deficits to manage the macro economy.” My economics, such as they are, come from studying it from an MMT angle so I’ve no prior exposure to more conventional thinking which may or may not be an advantage.

I would say that budget deficits are essentially neutral and aren’t a management tool in any case. If anyone gets a tax cut and they buy a government bond with their extra money the government’s deficit will increase but the spending level will remain much as it was.

On a general level, if we all save more, which an increase in interest rates could possibly encourage then demand would fall. The correct course of action could be (if there were no inflation problem) to cut taxes or increase Govt spending to maintain aggregate demand but we can probably assume that those in charge at the moment wouldn’t do this. At the same time the government’s deficit would increase (on the basis that everyone else’s savings equal the government’s deficit) which would lead them to think they should tighten up in either fiscal or monetary ways. Also, the “money supply” (however this might be defined) would likely increase due to the Government having to pay out more into the economy. So the conventional theory leads some economists to want to do precisely the wrong thing.

I recognise that we do have an inflation problem at the moment so this is not a time to allow fiscal policy to be too loose. However, this is not at all the same thing as fretting about the size of the government’s deficit or the level of the money supply.

Rishi Sunak has said that we shouldn’t allow fiscal policy to be too loose or inflation will worsen. So he’s implicitly acknowledging that the original monetarist assumptions were incorrect and that we shouldn’t be expecting the BoE can be solely responsible for inflation control.

It’s ancient history now, but as I remember it monetarism was part of the small government movement, which was led by Mrs T and Ronald Reagan. There was an expectation that budgets would be balanced. Discussions then ensued about automatic stabilisers in the event of a recession. There seem to be few advocates for this point of view now. Most economists seem to think that fiscal policy was an appropriate response to the crash, and to stave off the threat of depression. The argument was only about how much. Many thought that fiscal policy was too loose on that occasion – one reason that people shrugged when the floodgates were opened for the pandemic. Arguably that is what set inflation off this time. In fact a lot of the issue is the savings behaviour of the public. The effect of government generosity during the pandemic was delayed because people saved much of it until a bit later. Incidentally at the time of monetarism the idea that fiscal policy was neutralised by savings behaviour, and therefore pointless as macroeconomic tool, was quite popular. But monetarists never really thought through the behavoural reactions to monetary policy.

As you say Sunak is in a complete muddle. He says the Bank is responsible for inflation, and therefor to blame. But number one government priority is to bring inflation down – suggesting that it might be the government’s responsibility after all.

Yes. I think we are basically in agreement. The Government, I’d say rightly, was running a large deficit during the Pandemic when inflation was still very low. So it’s not the size of deficit itself which can be said to be the cause of the inflation but the rate of change, ie the reduction, in the deficit afterwards as everyone else made use of the extra money in the economy to try to increase their spending power. Especially as this was happening at the same time that there were supply problems caused by Covid itself and the Ukraine war. Many would add Brexit but I’d say this was relatively small and mainly due to lower paid workers making the most of their increased bargaining power, why some of us would think was a good thing on balance.

You’re right about the savings, and spending, behaviour of all of us. I’d perhaps just say that “all of us” should also include our overseas trading partners. It doesn’t make any difference, pound for pound, if it’s you or I doing the saving domestically, or some overseas country which might wish to run trading surplus with us. If we’re saving it means we’re spending less than we’re earning. This has to mean that Government will be spending more than it is earning.