Thank you to Politcal Betting’s Alistair Meeks for giving me the idea of using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to offer insight to Britain’s referendum on whether to leave the European Union. It poses an interesting conundrum about the campaign for a Leave vote.

Thank you to Politcal Betting’s Alistair Meeks for giving me the idea of using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to offer insight to Britain’s referendum on whether to leave the European Union. It poses an interesting conundrum about the campaign for a Leave vote.

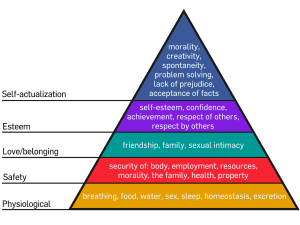

Maslow’s hierarchy is old-fashioned psychology, which has no doubt been left behind by practising psychologists long ago. But it contains enough truth to resonate with political analysts. This hierarchy is presented as a series of layers, usually visually presented as a pyramid. At the bottom are physiological needs (food, shelter, etc.); at the top is “self-actualisation” – the higher needs of confident people. The idea is that while needs are unmet in lower layers of the hierarchy, higher needs will count for little. People won’t worry about safety if they are starving, and so on. The political message is that high-flown arguments about democracy and freedom will not appeal to people unless more basic needs and fears have dealt with.

Mr Meeks puzzles that many Leave campaigners are obsessed with the European Union, and its supposed effects on national sovereignty, and yet the EU hardly registers in lists of important issues identified by ordinary voters. It is trumped by issues such as the economy and immigration, which speak to needs (security and, perhaps, belonging) that are lower down the hierarchy.

But the puzzle doesn’t end there. The Economist’s Bagehot column points out that there is a great educational divide in attitudes to the EU, and uses two nearby cities to illustrate the point. Middle class, well-educated Cambridge is strongly for Remain; working class Peterborough is the opposite. And here’s the puzzle: it is the middle classes, much further into self-actualisation level, to whom the standard Leave argument about sovereignty should appeal. And it seems to be having little or no impact there.

And that is not from lack of exposure. For the last five years people on BBC Radio 4 have been banging on about it, and not just in news programmes. Arch Eurosceptic MP John Redwood presented an Analysis programme on Europe; conservative philosopher Roger Scruton majored on it in one his Sunday morning point of view programmes. And it has been repeated endlessly in the last week, most notably by Conservative cabinet minister Michael Gove, usually reckoned to be a thoughtful type, as well as the more opportunist Boris Johnson, London’s Mayor. And almost no argument has been offered against the idea that the EU is an outrageous assault on British democracy and in effect a foreign dictatorship. Instead responding Europhiles quickly migrate down the Maslow hierarchy and talk about jobs and security, or pick off relatively minor points, such as challenging the figures on Britain’s budget contribution to the EU. And yet for all the apparent one-sidedness of the high intellectual debate, Remain seems to be winning at the top of the Maslow pyramid.

I think that is because there is a massive disconnect between Leave campaigners and members of the general public on the nature of Britain and democracy. Mr Gove paints a picture of a proud history of the British freedom and democracy, against an EU that has achieved little and is stuck in the past. He wants laws made in Britain, by lawmakers the British people can throw out if they don’t like them. But it is all very well for Conservative MPs holding safe parliamentary seats to wax lyrical about British democracy (and to talk aggressively about throwing the blighters out – a very distant prospect I their own personal cases…), and decry the limits that the European treaties place on their exercise of power – but ordinary people, even nice, educated, middle class ones, don’t feel connected to their lawmakers. They distrust their parliamentarians, and aren’t sure that they actually would be “thrown out” if they didn’t like them. Indeed when it comes to elections, the same politicians delight in suggesting to electors that they have no real choice at all – vote for them or for chaos. And don’t waste your vote on Greens, Liberal Democrats or Ukippers. Many voters are persuaded to vote for people they don’t really like or trust, for fear of something worse. It is hardly surprising if people have rather more nuanced views about British democracy than their elected representatives.

This is all reinforced by standard political wisdom. Democracy is not supposed to be elective dictatorship. Hitler’s attack on minorities and opponents was not legitimated by the fact that he had a mandate from an elected parliament. As the Americans appreciated from the start, freedom and democracy is about checks and balances. And there are frighteningly few of these against the British House of Commons, whose majority, these days, is based on the votes of about a quarter of the electorate. The European Union presents one of the few remaining checks, and usually for reasonably sensible things, like protecting the environment, ensuring public procurement isn’t stitched up, or that there are some standards of job protection. These regulations may not be especially loved, but they offer some bastion against our own politicians, especially Conservative ones, who celebrate the freedom of employers to sack people at will, and landlords to do as they please. The EU is not imposing taxes or calling up our young people to serve in a European army. This “dictatorship” has a rather muted impact on our daily lives, it turns out, which well be rather benign in the long run.

There is another problem with the sovereignty argument. What is so special about the British level of polity? Mr Gove is annoyed that French or German politicians have a say over our laws. But don’t Scots voters feel even more strongly about the say of English Conservatives over theirs? Why should London voters have so much say over what goes on in Manchester or Cornwall? Politics is clearly a much more complex business than is being made out. It is interesting to deploy the arguments of Messrs Gove and Johnson to the question of Scottish independence. And to note that to most Scots the EU does not look like an instrument of foreign oppression.

Furthermore, many middle class voters may be rather less than convinced that the rest of Europe is such a bad place that we should have nothing to do with them, or (a longer shot) that the EU has achieved nothing. Things seem to work well enough in France, Germany and Austria – and even in Spain and Italy. The EU’s mission to extend democracy and the rule of law to south and east Europe may not be entirely successful or complete, but surely it is a worthy cause? And surely the most important moments of British history, from Waterloo to the First and Second World Wars show that what happens over the Channel affects us deeply. Europe is where Britain belongs, surely?

This is not to say that there are not many insecurities that the Leave campaign can play on, especially amongst working-class Britons. These, especially including fears over immigration, may yet win them the referendum. But banging on about sovereignty is unlikely to help them much.