Somewhere over the Christmas holiday I heard on BBC Radio 4 a very authoritative gentleman suggesting that Britain should copy Japan’s economic policies. Alas I didn’t catch who it was, and can’t trace him. I think he was on the World at One, but these days the BBC doesn’t let you search past programmes for particular items. Anyway, it is an excellent illustration of the point that I was making about the British economy a couple of posts ago. It’s worth explaining why he is so wrong. I suspected that the gentleman was a graduate of PPE at Oxford, like former Prime Minister Liz Truss: a degree course that equips its subjects to sound plausible when talking about economic policy, without necessarily grasping even the basics of the subject. Ms Truss did not seem to realise that reducing inflation meant limiting demand.

The particular set of Japanese policies the interviewee referred to dates from a number of years back, and was advocated by the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and is often referred to as Abenomics. He himself called his approach as the “three arrows”. This was based on the ancient wisdom that while it is easy to break the shaft of a single arrow, it is hard to break the shafts of three arrows bound together. His three arrows were monetary policy (ultra low interest rates supported by Quantitive Easing (QE), i.e. the buying of government bonds by the central bank), fiscal policy (extensive infrastructure investment funded by budget deficits) and supply-side reforms. All these policies were mutually reinforcing. Supply side reforms were required to expand the capacity of the economy, fiscal policy to ensure that aggregate demand met this this expanded capacity, while loose monetary policy made the large government budget deficits implied by this sustainable. Without all three strands of policy, there would be failure. Japan had endured many years of economic stagnation, and Abenomics was an elegant and coherent approach to this – more than can be said for British policy economic policy since 2010, when the different policy levers often seemed to work against each other.

The interviewee did advocate one point of departure from Abenomics. When explaining supply side reforms, he advocated three “Is”. The first of these was “investment” – I can’t remember what the other two were (perhaps “institutions” was another). Investment was not a focus of Abenomics. Fiscal policy was directed at public investment, admittedly, but there was little economic coherence to this – it. was mostly about the dispensation of political favours (“bridges to nowhere”) – and the desired economic impact was to raise aggregate demand, not to expand economic capacity. Supply side reforms were aimed at non-financial barriers that were holding the economy back, such as the low rate of employment of women, and not investment.

So what’s wrong with all this in the British context, skating over its mediocre results in Japan itself? Japan was, and is, in a very different economic place. It has a robust industrial base which routinely delivers export surpluses, in spite of having to import raw materials and energy. It has a high rate of domestic savings (in other words domestic consumption is much less than income). Investment is plentiful. But it has all manner of market inefficiencies due to conservative business practices and cultural mores (for example severe prejudice against working women). Contrast this with Britain: its industrial base is comparatively weak, delivering no trade surplus so far this century; the private savings rate is low; investment is weak; but business practices, regulations and social mores are as conducive to economic efficiency as they are anywhere in the world – with a high rate of overall employment, for example. Both countries share grim demographic trends, with a reducing ratio of people of working age – though Britain has been mitigating this with immigration on a scale that Japan doesn’t.

What ails Britain? Pretty much everybody seems to agree that the country lags other developed countries, though whether you compare with America or with Europe depends on your politics. Apart from the lacklustre growth record since 2007, the main evidence is poor comparative statistics on productivity. A lot of the analysis is very shallow, however. Even many academic economists who should know better are susceptible to the fallacy of composition. While they quickly recognise that national decisions on budgeting and demand management are not the sum of individual household budgets – and what would be right for a household would not be right for the country as a whole – they fail to see the same thing on the supply side. They often talk of the country’s production side as if it is a single business (“UK plc”), but that is grossly misleading.

For a start, the supply side of the economy is very heterogeneous. Computer factories are highly productive; hospitals are the opposite. It doesn’t follow that we would be better off if we closed our hospitals and replaced them with computer factories. Furthermore, if individual businesses become more efficient, it also does not follow that this translates into the whole economy doing so. That depends on what those individual businesses do with their extra efficiency. They might expand production, perhaps helping to expand the economy as a whole – provided that there is latent demand for their product. If this happens there may be a virtuous circle that helps the whole economy grow. Or they might just keep production levels steady and sack some workers, paying extra dividends to investors who use it to invest in other businesses. Or the directors may pay themselves more in bonuses to spend on personal trainers, luxury goods, and other things where low productivity is the essence. Overall there is a well-established pattern, however, referred to by economists as the Baumol effect. As productivity advances in some sectors of the economy, lower productivity industries come to occupy a higher proportion of the economy as a whole. The balance of wealth creation (highly productive industry) to wealth realisation (the part of the economy that prioritises self-actualisation and typically has a high human content – i.e. low productivity) shifts towards the latter. What’s the point of being rich if you can’t access decent healthcare, drive around in Bentleys or eat organic food?

The problem for Britain is that the overall mix of its economy is out of kilter. It imports a disproportionate share of the goods and services where productivity is very high, while producing too much of the goods and (mainly) services that are critical to quality of life, but where productivity is low, and export potential is much weaker. The answer isn’t to try and raise the productivity of the latter goods, as this will tend to kill the quality. It into rebalance the production side of the economy towards high productivity goods that can be exported. There is another way of looking at this problem: it is that British consumption is too high. We are living beyond our means, importing more than we export. Consuming less would give the supply side of the economy the chance to rebalance in favour of exports. This is the opposite problem to Japan, where aggregate demand tends to be too low for economic efficiency. In Britain there needs be more private saving and more investment. In Japan it is the opposite.

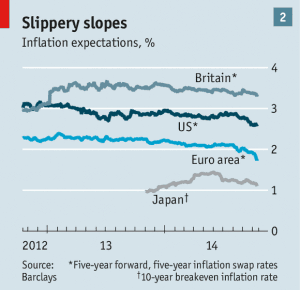

So Abenomics would not work here. Looser fiscal policy would push us into inflation. Loose monetary policy would simply build speculative bubbles. Supply side reform would not make enough difference, though doubtless there are some useful things to do.

But the interviewee was right about one thing: the key to progress in Britain is greatly increased investment. Any move to highly productive, high exporting businesses will entail substantial investment. What are these businesses? Basic economics teaches us that these should focus on areas where the country has a comparative advantage – but that is a very slippery thing to identify. We shouldn’t be chasing a past golden age, or trying to directly copy other successful economies. If you care to look, there are areas of promise – for example life sciences, especially if the country can tap into NHS patient data. The government, at least does seem to appreciate this – it talks about building the industries of the future. But it struggles to deliver the right economic conditions to generate the level of investment required. There are not enough private savings to fund the business investment required; too much of what there is disappears into government debt – pushed that way by conservative regulation.

This points to a different three arrows to those advocated by Mr Abe. We need to incentivise more equity investment in businesses with export potential – especially if these are based outside London and the South East. Much of this must be led locally by regional and local governments, able to raise their own revenues. Pension regulations need to be overhauled. Second we need a much tighter fiscal policy in order to damp down private demand and keep inflation in check – this will consist of higher taxes and more efficient government (e.g. coherent public services that solve problems rather than passing the buck). If the public won’t save more of their own volition, then the enforced saving of higher taxes has to do the job. This would then give the government space to kick-start investment and tackle bottlenecks. Third monetary policy should primarily be focused on creating a healthy climate for savers, and ensuring financial stability. That will surely mean higher interest rates.

No politicians can advocate steps two and three of this programme. But the first part is near political consensus – and we could find that it drags fiscal and monetary policy in its wake. British policy usually advances by muddle. It is possible that the country will muddle along in the right direction. That is the best we can hope for.