I apologise for not posting for some time. Feelings of futility and despair at politics have made gardening and painting model soldiers a more attractive pastime. I started an article last week, but this collapsed in a muddle. This time I want to step back and set current debates over the political economy in the broader historical context – to suggest that we need to adjust our expectations to profound changes to the way economies work. Above all this means letting go of ideas about economic growth and all the baggage that goes with it. The implications for our politics are profound.

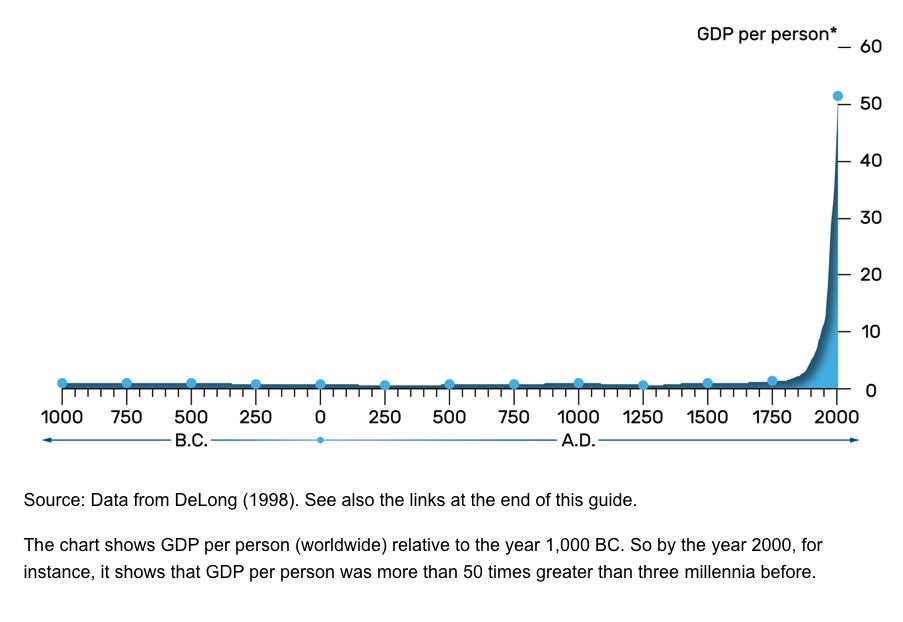

Economists sometimes like to portray their discipline as the description of immutable laws. They show tables of statistics (or rather graphs – see above) going back centuries – with uniform metrics such as income, prices and productivity. The idea is to present the economy as a continuum, even if as the world behind it changes. This might lead us to think that the tools of economic management are of timeless relevance. What if Keynesian demand management had been discovered earlier! But this is really an attempt to project the present back into history. The world has been changing profoundly over the last three centuries and the economy with it. With these changes come changes to our ideas of what economic management is about, and politics with it. But the process is slow and complex, and it can be hard to appreciate it at the time. That’s why I think it is helpful to paint a picture of how things have changed in the past, to give an idea about how things might be changing again now. I like to rationalise the past into a series of epochs – but, of course, each each moved seamlessly into the next. This narrative is based on how things were in Western Europe in particular, and by extension its colonies in North America.

The first epoch was the Age of Subsistence, from Medieval times into the 18th Century, which was overwhelmingly agricultural and marked by stasis. There were important technological developments, and the changes to trade patterns also had important impacts. Textiles, mining and iron working played a role, leading to occasional local booms and some nice stone buildings for us to see today. There was sufficient agricultural surplus to support a number of cities and towns. But the overall picture was fairly static and based on agriculture, mostly of a subsistence nature. The vast majority of people worked on the land in a very low-productivity agrarian economy. The big political idea was that people should know their station and not get beyond themselves. The idea of abolishing poverty was considered to be delusional nonsense. God created a world ever divided between the aristocratic rich and the peasant poor, and that was that.

Then came the Industrial Revolution, which was initially based on textiles and agriculture. Farming became more efficient, not so much directly from changes in technology, as from the application of scale economies, with enclosures and evictions. Agricultural surpluses could be moved by canal, and the cash economy expanded. Labour moved to textile mills, where mass production techniques were developed. Also at this time slave labour was used in overseas colonies to produce such products as sugar, tobacco and cotton. Trade grew in importance and a substantial middle class emerged. Social mobility became more of a feature of society. A lucky few managed to climb from working class to middle class; an even luckier minority of middle class people aspired to the aristocracy. But the labouring classes saw no improvement in their lot. There was no move to reduce poverty. But the new middle classes questioned the ways of the governing elites and this had a profound political impact – most notably be the American and French revolutions – but also with such things as the anti-slavery movement in Britain.

This moved, in the 19th century, to the Age of Heavy Industry. This saw the rise of railways and steel. Infrastructure (railways, ships and sewers for example) and armaments became the centre of attention. Right though until the middle of the 20th Century, economic success was measured in terms of the rise of heavy industry. Hermann Göring’s statement that “Guns will make use powerful; butter will make us fat,” summed up the way that most people thought about economic policy. Stalin’s building of Russian heavy industry at the cost of millions of lives was generally considered to be tough but rational. But improving the lot of the poorest did start to command political attention, as working class movements rose. Sanitation improved, free education was offered to all, and a welfare state started to emerge. This age culminated during the Second World War, which was largely decided by industrial production. But it quickly morphed into the Age of Light Industry. Many of the technological developments forged in the war, such as plastics, turned out to have applications in consumer products. And the need to switch away from war production offered the opportunity to greatly expand the production of mass market consumer goods. Pretty soon mass consumption was considered to be the top priority for the political economy. The concept of economic growth was developed to reflect this and the prospect of abolishing poverty. The West won the Cold War because the Soviet empire could not compete in the production of consumer products, and its leadership lost confidence in their raison d’être.

Something else profoundly important developed alongside the consumer economy: the rise in the role of the state. The state greatly expanded in wartime, intruding into all aspects of life. People noticed that rationing meant that austerity in the nation as a whole did not mean that the poor had to starve – indeed nutrition for the poorest improved in Britain. This vindicated a role for the state in providing a social safety net, with health insurance, unemployment pay, expanded pensions and so on. Productivity was high enough for agriculture and consumer goods that there was room for a growing state sector. Politics became managerial, with politicians promising to offer prosperity to all. Social mobility exploded.

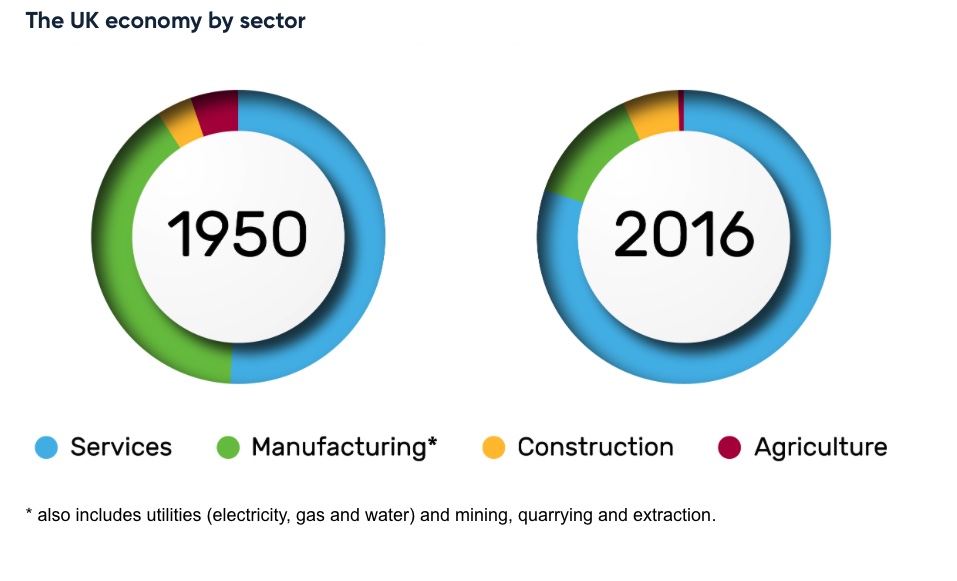

But the world has moved on. Many noted a major change in political and economic thinking in the 1980s, following he economic travails of the 1970s. There was a push-back on the growth of the state and on organised labour. De-industrialisation started to take hold as productivity continued to advance in manufacturing. The rise of Asia, starting with Japan, offered gains from trade as cheaper manufactures could now be imported. But growth in consumption still dominated expectations. Manufacturing industry was still considered to be the core of the economy, much as agriculture would have been in the 18th Century.

To understand how things have changed, consider a few things about the world around us, in developed economies. First are the signs of saturation in consumer demand. Of course there are plenty of people struggling with the basic necessities – but they are a minority. Meanwhile people buy cars absurdly over-specified for their needs, and leave them parked outside their homes doing nothing most of the time. People buy clothes to wear once or twice before they are discarded. Much of people’s wealth is spent chasing things that are not made – notably land for homes, even if just for temporary residence rights. A lot of “consumption” is in fact about the acquisition of status symbols.

Then there is the idea that consumption is actually bad for us. Environmental degradation is one example; climate change is another. And then there is health. Highly processed foods, where agriculture and manufacturing meet, are clearly damaging to our health, and one reason that life expectancy is now in decline. And yet to economists they are ideal commodities: based on high productivity and promoting over-consumption, and thus with beneficial economic impacts. Better off people increasingly choose products that are healthier with reduced environmental impacts (though still prone to massive over-consumption) – but these imply reduced productivity – the biggest crime there is in the Age of Light Industry.

And then there is changing meaning of “quality of life”. Once this meant being able to consume commercially produced things to the maximum extent. But increasingly this is taken to mean working less hard. People take earlier retirement if they can – notwithstanding that many are physically able to work for longer (your blogger is guilty as charged). The recent pandemic has led to an explosion of demand by employees to work from home – even if it means being paid less. Evidence mounts that this reduces productivity, but most employers are forced to compromise. Working longer – or expanding the workforce – is, after raising productivity, one of the core strategies of a growth economy, and it is being thwarted.

Consider health care too. This comprises a growing share of the economy (in some places it employs more than manufacturing, I suspect). But it is is peculiarly ill-suited to the sort of quantitative analysis that likes to see things in terms of output and productivity. New therapies are developed; these solve problems that were unsolved before – but often require a greater level of inputs. Demand is insatiable; the share taken of the total economy grows.

And economic growth is slowing, much to the worry of economists. Many of these point admiringly to the more “dynamic” American economy – but Europeans question whether small holiday entitlements, poor life-expectancy, terrible inequality, and high environmental degradation are actually worth it. What if slow growth is the result of the freely made choices by those welfare-maximising agents, beloved of classical economists? Economists and politicians have to adapt to the reality – rather than try to make people behave according to an outdated model. This was the terrible strategic mistake made by British prime minister Liz Truss’s catastrophic regime.

The overall narrative is easy to see if you are willing to look. Technology has so advanced, and environmental imperatives have so grown, that a focus on people’s true interests and wellbeing does not involve increased levels of consumption – and will often lead to reductions. Investments in new, cleaner energy infrastructure will create jobs but not lead to economic growth in the sense that we have understood it since 1945. But where this leads is harder to discern. Politicians are right to worry about the lack of growth. Demand for public services remains high, but the economic model for managing supply and demand is breaking down. The current model is that people pay taxes, which limits demand for private sector goods, allowing economic space for public services. But if demand for private services stagnates or declines, while that for public services expands, this means that taxes have to rise. That is a political challenge – the connection between what you personally pay in tax and how you personally benefit from publics services is a weak one. That becomes even harder if the size of the workforce stagnates or declines because people would rather not work, and have sufficient savings to fulfil that desire.

So far politicians, economists and, indeed, the public at large cannot imagine a way of meeting the crisis in public services without stoking economic growth. The Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer, says that growth is at the heart of his strategy for government. But it won’t work. And this fact, and its consequences, will dominate politics in the coming decades.

Advances in technology give us the opportunity to continue advances to human wellbeing, even while reducing harmful impacts on the environment. But assuming that this will come abut through economic growth is mistaken. We need a new language to describe the economy. In future posts I will try to develop ideas about what his actually means.