Back in the 1970s there was a persistent story about lightbulbs (then incandescent tungsten ones) that was trotted forth to demonstrate the madness of capitalism. It was that the life of a bulb was kept deliberately short so as to create demand for replacement bulbs. Apparently it was true – but nobody cared. Whinge as we might at the fringes, politicians and the public were happy to keep the economic treadmill going. Longer-lasting lightbulbs would mean fewer jobs. Those days are long gone. Our lightbulbs now are immeasurably more efficient, and they aren’t built to self-destruct. Few jobs are at stake, and even fewer jobs in countries that use the bulbs. This leaves the world materially much better off. But politicians and economists alike hanker after the those old days – hence their obsession with economic growth.

Even serious economic commentators like the Financial Times’s Martin Wolf can’t break this: Mr Wolf started a recent column with the words: “If the UK’s real gross domestic product per head had continued on its 1955-2008 path, it would now be 39 per cent higher.” This implies that the lack of economic growth in the last 15 years is a failure of economic policy, and not due to a change in the way the modern economy works. This is wrong: instead we should think of the second half of the 20th Century as a unique period in economic history – and recognise that we have long since entered a new era, one in which sustained growth of gross domestic product per head is not a feature – nor even really desirable. Life can get better, but not through consuming ever more stuff.

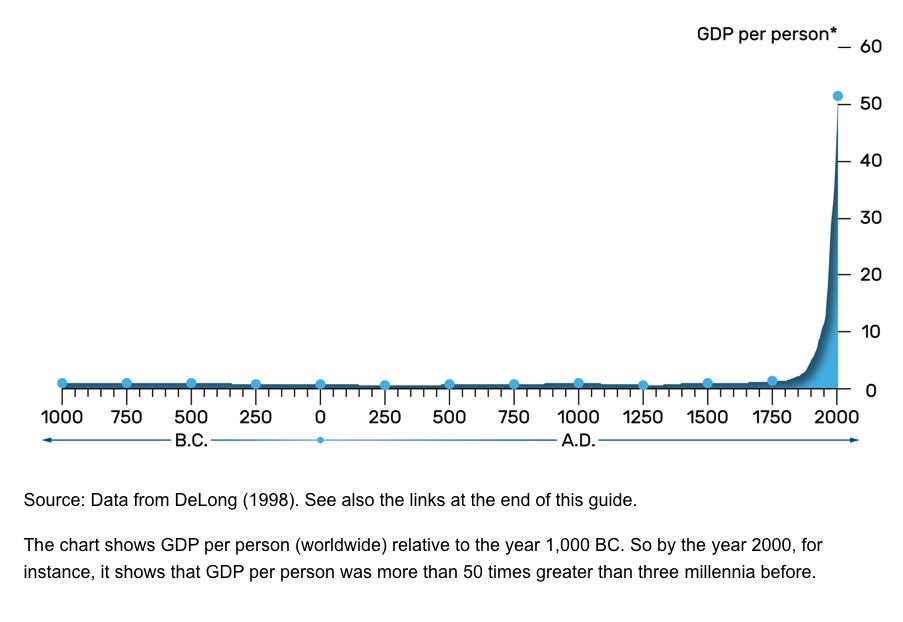

Economists don’t like to look behind their beloved aggregated economic statistics, which they like to treat as classical physicists once did the measurements of pressure, temperature and volume of gases. What the gas molecules were made of didn’t matter. Some economists try to construct historical time series of centuries and more in an attempt to build a narrative of economic policy, as if to say that there are common economic principles that are everlasting. To them the post-war era in the developed world, and parts of the developing one, featuring consistent growth is a model of wise policy. Firstly through good macro-economic management, with Keynesian demand management, and then inflation targeting monetary policy: these smoothed out the dips and troughs that were a feature of previous eras. Then there was a consistent advance of productivity through the use of new technologies and more advanced management. “Productivity is not everything,” said the economist Paul Krugman, “but in the long run it is almost everything.”

But looking back on it, that golden age was the result of the convergence of four factors, each of which has reached its limit: the post-war baby boom, bringing women into the workforce, the expansion of world trade, and the rising consumption of manufactured goods. The baby boom expanded the proportion of the workforce that was of working age, but by the 1980s the babies were now all of working age while the birth rate had fallen; and as the boomers reached retirement age in the 2000s, the proportion of people of working age shrank. The economist Dietrich Vollrath did the maths and found that this accounted for most of the tail-off of economic growth per head in the 2000s in America – and in Britain the effect would have been greater, if anything. This led to my comment that “Demographics is not everything, but it is almost everything.” The war brought many women into the workforce, but in the 1950s the convention that married women should stay at home remained powerful. But as families wanted to spend more on consumer goods and property (and technology made housework easier), women were steadily brought into the workforce, increasing the overall rate of employment, and thus driving growth. This trend has been slow but steady – the proportion of women at work was still growing through the 2000s – but now there is not a big difference between male and female employment, and in most economies, including Britain’s, the limit has surely been reached.

Freedom of trade has also been an important driver of economic growth, as the laws of comparative advantage and economies of scale came into play – in notable contrast to the pre-war years. First came GATT – the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, part of the great post-war settlement. Then, for Britain, there was membership of the European Economic Community – which in turn was given a major lift when this morphed into the European Union with its Single Market. But perhaps even more significant was the steady rise in Asian economies, and the huge increase in trade in manufactured goods – a succession starting with Japan, moving through to the Asian “Tigers” (Taiwan, South Korea and so on) onto China, with India in a supporting role. The rise of this trade, referred to as “globalisation” was transformative. The cost of manufactured consumer goods in the early 2000s tumbled as a result, and was one of the critical underpinnings of economic growth. But this trade is no longer growing – and is probably shrinking, while Britain has left the EU and Single Market. Gains from trade are unravelling. This is partly a product of the rise of protectionist politics, but it is also because economic convergence has reduced the potential gains from comparative advantage. Funnily enough the reversal of globalisation is often celebrated by politicians, almost in the same breath as they call for stronger economic growth.

These three factors are well-known amongst economists, even if they don’t talk about them enough when considering the slowdown of economic growth – compared to familiar targets such as lack of public and private investment, NIMBYism, muddled political policy and so on. In contrast my fourth factor seems to be less well understood. In the post war era there was a massive expansion of consumer goods, from cars to cosmetics. This was made possible by advances in technology during the war, with the development of plastics, for example. Keynesian economic policy helped to pump-prime a virtuous circle of increased supply and demand – the expansion of manufacturing and distribution jobs helping to fuel demand. This cycle became central to the growth of advanced economies, copied by many less developed economies, though, interestingly enough, not so much by China, which is another story (they channeled much more of the extra demand into investment, relying on exports much more for growth). Along the way absurdities like the built-in obsolescence of light bulbs were tolerated. Many view this era, up to the late 1970s in Britain, as something of a golden age: one with a largely stable working-class culture, geographically well-spread, and quite a bit of upward mobility into an expanding middle class – before the destruction of the industrial heartlands that started in the 1980s. This view requires rose-tinted spectacles. Some things were clearly better then: access to social housing, for example; and this, combined with high taxes on the rich meant lower inequality and better social cohesion (so long as you weren’t brown or black skinned). Public services were more generously staffed, though usually terribly managed. But was an era of massive environmental degradation and plenty of social strife; film and television dramas of the era depict people shouting at each other but failing to communicate – which is largely how I remember it as I was growing up.

But this age of expanding consumerism could not be sustained. There are only a certain number of cars, fridges and so on the people can own. There was a limit to the amount of electric light that people could constructively use. And besides, advancing productivity meant that fewer jobs were required to sustain demand, and expanding trade kept up fierce pressure on efficiency. The final blow came when when, for reasons of comparative advantage rather than efficiency, the developing economies of Asia took over a huge share of the production of consumer goods. The 1980s onwards saw massive closures of factories and other infrastructure, such as coal mines.

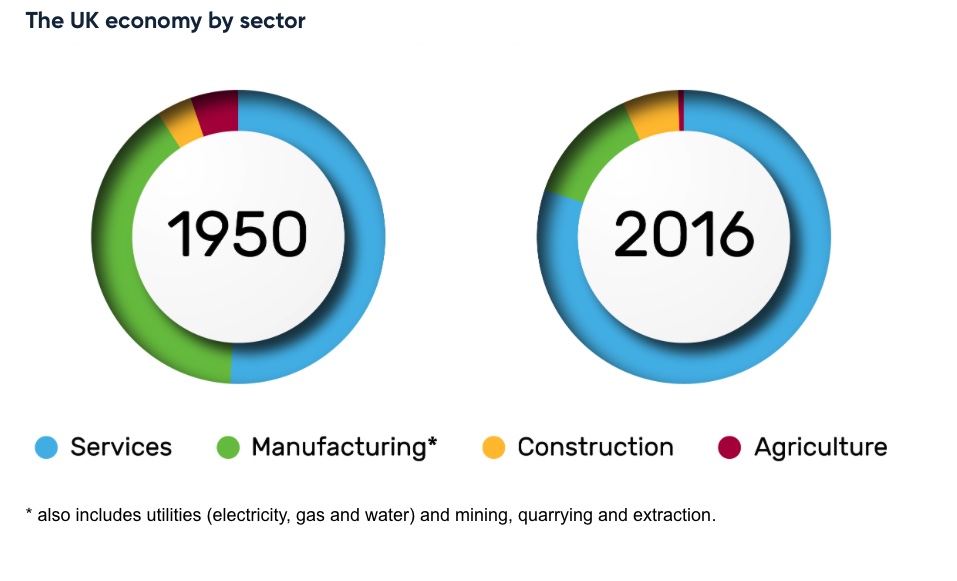

But the standard rejoinder to this from economists is that these developments shouldn’t really matter. Cheaper consumer goods mean that people have more to spend on other things, and these require people to provide them – and these people can be made more productive. Lightbulbs may have been replaced by cheap LEDs made in China, but the new technology can be arranged into much more complicated and creative arrays, which need people to design and install them. But there have proved to be a number of problems with this idea. Economists will admit that manufactured consumer goods have largely been replaced in the modern economy by services, where productivity is a much trickier thing. They call it “Baumol’s Cost Disease”, teach it in Economics Batchelor degrees, and then forget about it.

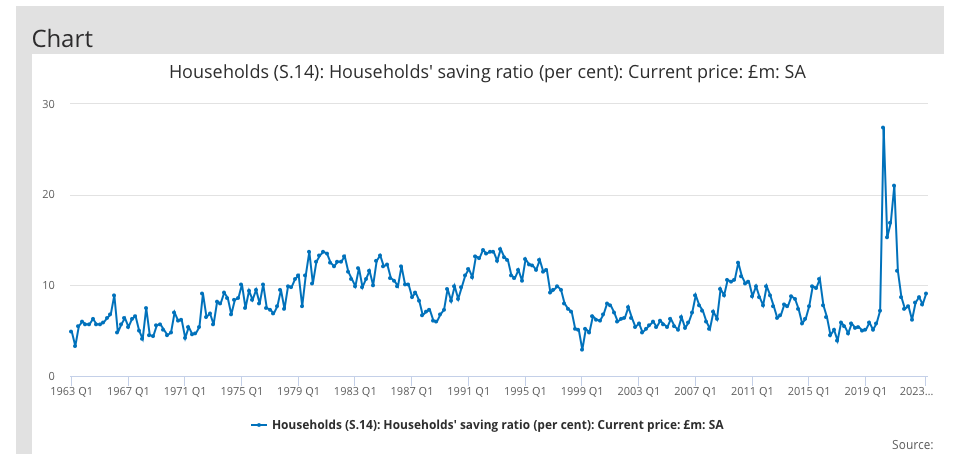

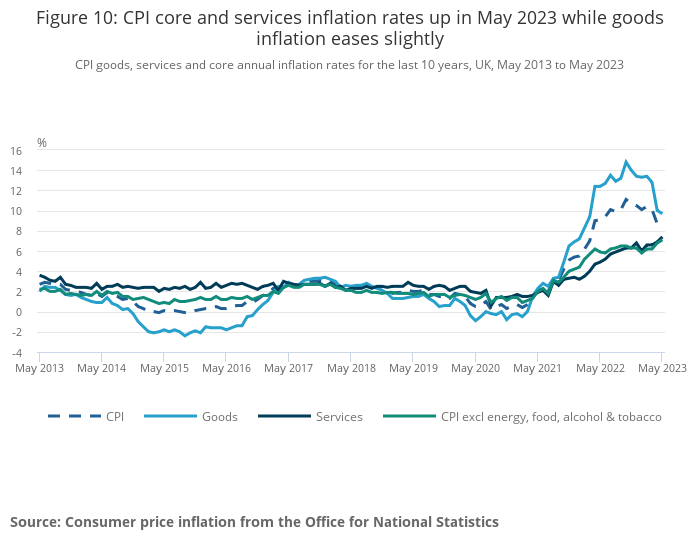

Unfortunately, a Batchelor Economics degree is as far as my formal economics training went. The theoretical complexities of an economy where increasing productivity comes about through higher quality rather than quantity, and were an increasing amount of consumption goes into access to land, rapidly takes me out of my depth. But the outcome of these complexities is surely that developed economies do not behave as they once did. One problem is that the modern economy is more unequal. Large numbers of people are now extremely well off by past standards, and we have the phenomenon of “mass affluence”. Millionaires are commonplace. But at the other end of the scale many working class jobs are much less secure than the factory and office jobs of the past. The better-off, meanwhile, spend a lot of their money is on status goods and services, rather than basics. (They also save more, which complicates things more – though overall savings rates have gone down rather than up). One of the key ingredients is human content. In olden times this might be the number of servants you employed; nowadays it is the consumption of personal services and use of products whose whole point is that their production processes are inefficient (hand-stitched handbags, etc.). These often require low-paid people to provide. There is surely a danger that this inequality gets entrenched, and that this is a drag on economic development. This is surely one reason that minimum wage policies have not caused the damage that a consensus of economists predicted in the 1990s.

Then you have the problem of leisure. One way for people to exploit the benefits of higher productivity is to work less. This might be more holidays, or (as in my own case) retiring early. Then there is the hobby economy – where people produce things deliberately on a non-commercial basis for the sheer enjoyment of it. All this is perfectly rational economically, but it makes a mess of classical economic assumptions. And here’s the thing: a society were people don’t have to work as hard to achieve a comfortable and fulfilling life is not a failure. But listening to conventional economists you might think it was. Such a society is taking shape through the freely made decisions of economic agents: it is not a failure of policy. We need to understand how much slow growth is the result humanity realising the benefits of greater economic efficiency, and how much is through dysfunction – and I will admit there still quite a bit of dysfunction about.

So what are my conclusions? Firstly it is that most economists are suffering from a fallacy of composition when talking about productivity and growth. They have a mental model of the supply side of an economy being a single business scaled up (“UK plc”) when the reality is much more complicated. Advances in productivity in one place can simply lead to a reduction somewhere else. Secondly we are often confusing the creation of wealth with its realisation. Many people rationally choose to realise wealth by earning less – and the number is growing. Thirdly, the inequalities in our economy aren’t just a bit of untidiness that will resolve itself, but need to be a central focus of economic thought and policy development – as this is likely to do more to advance economic wellbeing that overall economic growth.

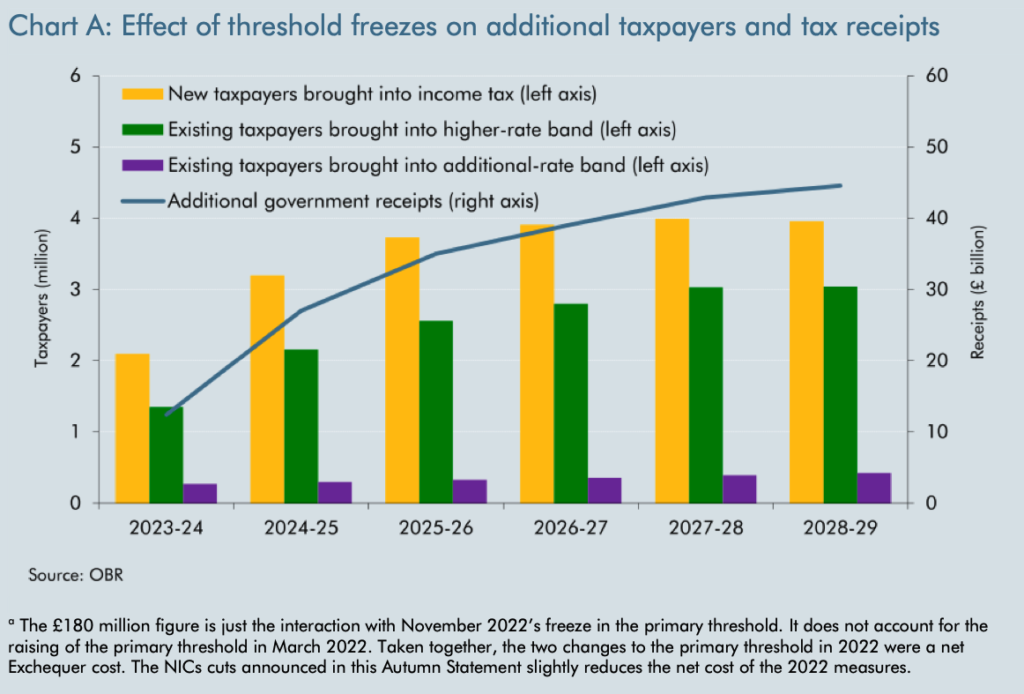

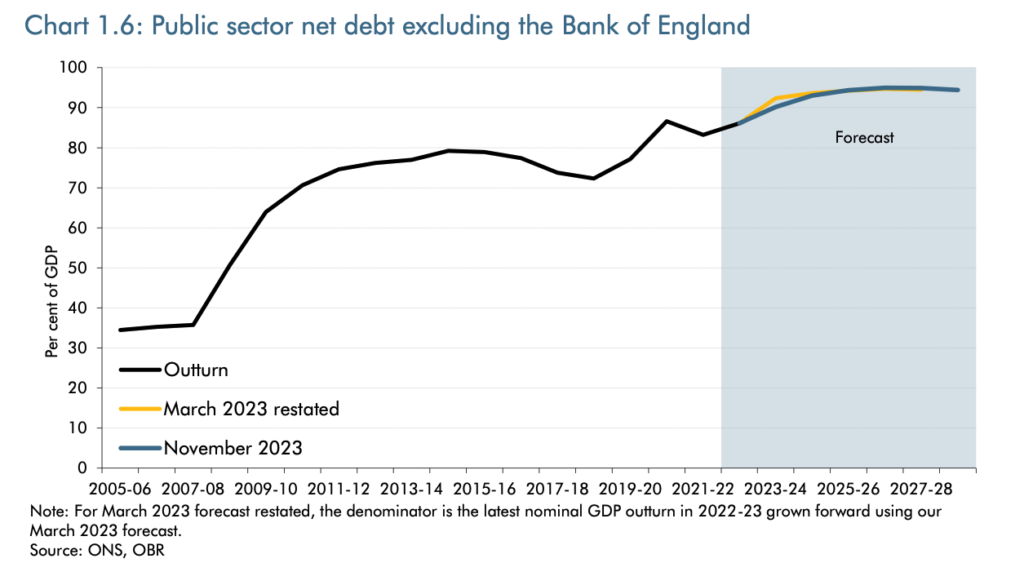

Politically this means that both the left and the right are barking up the wrong tree – at least as represented in Britain by the Labour and Conservative parties. Conservatives hanker after a low-tax high-growth society, powered by free-wheeling entrepreneurs. Those days are long gone. Lower taxes simply increase inequality and have nothing to do with growth. Labour assume that better direction from government towards constructive investment will unleash growth that will generate taxes that will fund improvements to public services. This is a lot less wrong-headed than the Conservative narrative. After the years of chaotic Conservative government, it is surely true that a bit of grown up government will unleash a some catch-up growth, enough to generate a bit more tax revenue – and maybe even to lift growth to the top of the G7, as Labour predicts (doubtless thinking that the other six economies are due for a bit of a stall…). But it can’t last – and the party is not ready for the hard choices that lie when it all fizzles out and they are forced to confront various combinations of austerity and higher taxes.

What we need to do is to take a fresh look at society and its dysfunctions and address that dysfunction through slimmer but more effective public services, and intelligent redistribution. Technological advance continues to offer the opportunity to advance human wellbeing – but we will get there faster if break the growth mindset.