The Economist print edition was published before Hamas’s shocking attack from Gaza, and led on one its own stories. I will stick with that story today. This blog isn’t meant for instant reactions and the dust is a long way from settling. All I will say is that I was a volunteer at one of the kibbutzes (Be’eri) attacked on Saturday back in 1979 – long ago but it still adds depth to my reaction.

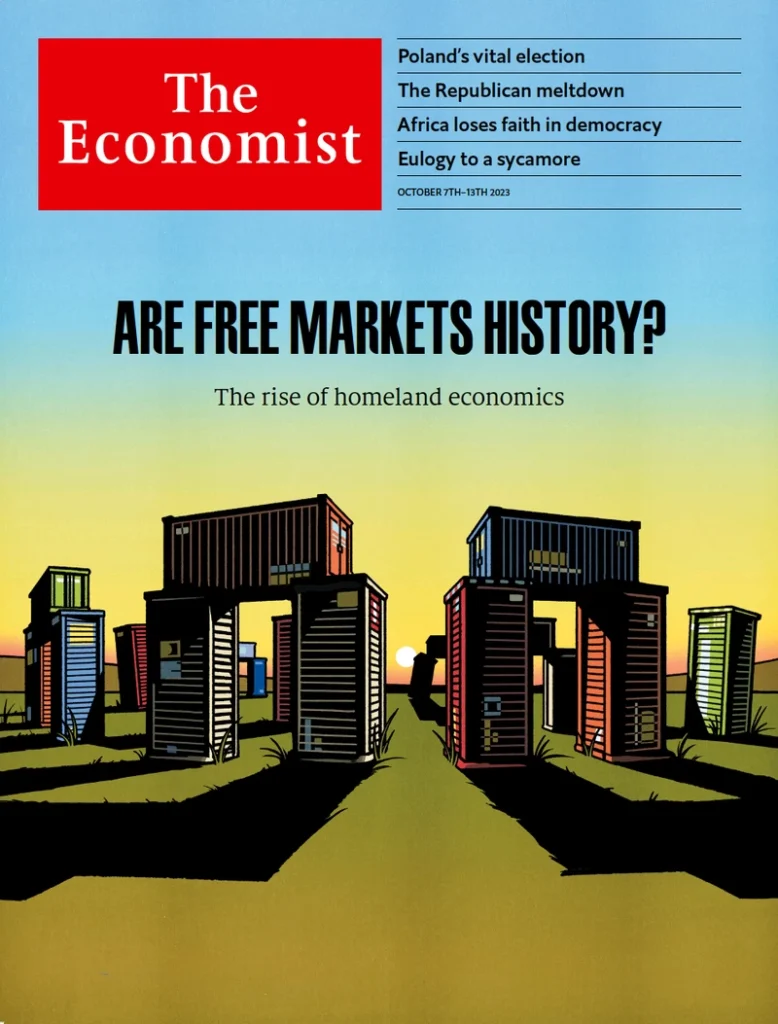

The Economist‘s lead is a challenge to “homeland economics” – the rejection of globalisation in developed economies, with the rise of protectionism and massive state subsidies to locate manufacturing in home country. The case is made by an extended essay (“special report”) on the world economy by Callum Williams, senior economics writer. This in turn is fronted by a leading article, Are free markets history?, which frames the issue as a challenge by politicians to the ideas of free market economics, which will lead to bad things. “Governments are jettisoning the principles that made the world rich,” it says. Having free market instincts myself, I find much to agree with in this critique. Most of the justifications offered for the increase in protectionism and extended government programmes don’t add up. But the newspaper’s writers are making three mistakes. They are taking the political narrative at face value without trying to understand the forces that shape it. They underestimate how much free markets themselves are driving the changes to the economic system. And they don’t know what they want. “The task for classical liberals is to prepare…a new consensus that adapts their ideas to a more dangerous, inter connected and fractious world.” Yes, but what on earth does that look like? It may turn out to be surprisingly close to what the world is doing now, but in slightly different clothes.

I see things differently – while at the same time using classical liberal economics as my basis. The expansion of global trade has been one of the most critical aspects of the development of the world economy since the Second World War. At first the main beneficiaries were the Western European and American economies – but this started to run out of steam in the 1960s – as the war-damaged economies of Europe recovered. Then Asia burst onto the scene, in three distinct phases – first Japan, then the “tiger economies” of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore – and finally and most dramatically with China – with India, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Bangladesh playing a significant role too. This last phase, from the mid 1990s up to the financial crash of 2007-09, was the most dramatic of them all and was given the monicker of “Globalisation”. The impact was dramatic – many scores of millions were lifted out of poverty; China rose to be a superpower; and living standards in the developed world (now including Japan) steadily advanced as falling prices of manufactured goods fed through. These advances had three critical ingredients: free trade, technology and comparative advantage. The weakness of The Economist‘s argument is that it concentrates on the first part of this holy trinity without appreciating the impact of the other two.

Let’s consider technology. The first critical development was the rise of manufactured consumer goods. Technological developments from the Second World War – from manufacturing technology to the use of plastics – saw a massive rise in the production of cheap goods from cars to washing-up liquid which came to occupy a dominant position in the economy. Advancing agricultural technology also led to huge agricultural surpluses in some countries. These goods are readily tradable and thus gave rise to a huge opportunity for trade. The second critical development was the advance of information technology in 1980s and onward, which allowed the development of long, global supply chains and the relocation of manufacturing and other economic activity, sometimes to the other side of the world. This again greatly expanded the scope for increased trade.

Then there is comparative advantage. This classical piece of economics has been well understood for two centuries and more. It gets taught in basic economics courses (“Economics 101”) as a wonderful illustration of the power of counterintuitive thinking. Then, after Economics 101, it quietly gets forgotten by trained economists. While its strategic impact is obvious, it is very hard to incorporate it into the mathematical and computer models that are at the heart of professional economics. That is unfortunate, because its dynamics are critical to understanding patterns of trade. It suggests that benefits from trade exist when two economies have structural differences that lead to different opportunity costs for different economic goods and services – for illustration the amount of wheat production that must be foregone by redeploying resources (typically labour) to make a car, say, or vice versa. In an undeveloped economy, like China in 1990, agricultural productivity is very low and you don’t have to forego much wheat to make a car. In America, agricultural productivity is sky-high, and the amount of wheat forgone to make that extra car is much higher, even allowing for much higher manufacturing productivity. So China is said to have a comparative advantage in car production, and America in wheat production – even if America is much more efficient at car production. So if China redeployed labour from the farms to factories and imported wheat from America to make up the shortfall, it could make more cars than the Americans would forego to redeploy labour to produce the extra wheat. Of course, that specific example is flawed: America can’t simply send workers to the countryside and expect that to raise agricultural production. But the general principle stands: export where you have comparative advantage; import where you don’t – and everybody should be better off. Exchange rates gravitate to levels that make the exchange beneficial to both sides, allowing for the differences in absolute productivity. This is one of the main reasons that exchange rates do not follow purchasing power parity.

Now the point that isn’t made in most Economics 101 courses, and fails to be fully appreciated by even trained economists, is that these gains from trade arise from differences in the structure of economies. If two national economies are identical, there will be no gain. And, in principle the more economies differ, the bigger the potential gains. Sometimes these differences arise from geography – if one country can drill oil in its jurisdiction it will certainly have a comparative advantage in oil over one that doesn’t – and production of oil will tend to drive out production of other goods (one reason why British de-industrialisation was particularly acute when North Sea oil was plentiful). But other differences are less rooted. The main difference that drove globalisation was the state of development – and in particular a vast, unproductive agricultural workforce compared in developing countries compared to a fully mechanised one in advanced ones. This did not necessarily drive agricultural trade, which is often subject to heavy protectionism, but led to low manufacturing wages, and thus an advantage in lower-tech manufacturing. But as these economies developed, starting with Japan, and moving on to China, they converged with the developed world. Manufacturing wages rose and the exchange rate of the developing nations appreciated. The gains from trade were based on much more subtle differences, and there were generally less of them. Outsourcing manufacturing from America to China is a much more nuanced economic proposition now, even without all the political baggage.

The role of technology in trade has changed too. Manufacturing technology has advanced to the point of being so productive that its role in the overall economy is much less dominant than it was. Indeed The Economist points out that one of the issues with relocating it “back home’ is that it doesn’t bring many jobs with it – it will not be recreating the good old days of plentiful mid-level jobs in the 1970s. Technology itself continues to evolve at a rapid pace, but it is far from clear that it is doing so in a way that opens opportunities for trade. It may even be doing the reverse by making it easier for economies to be self-sufficient after paying due homage to the technological giants that control so much of it. And the tech giants do not employ all that many people.

So it’s not at all surprising that the bottom is falling out of globalisation. There are just fewer opportunities to make profits. And with this tightness comes political sensitivity. It is much more likely that government policies will affect trade patterns because it takes less effort to turn the tables. And other issues such as resilience and security weigh more heavily. In particular China’s unsubtle effort to tilt economic advantage its ways in particular economic sectors, and use economic leverage to bully (countering, no doubt they would suggest, the American propensity to do the same) is drawing an understandable political reaction.

Where The Economist is right is to suggest that the new developments in structure of the world economy will yield disappointing results, especially in the developed world. The loss of gains from trade as a result of convergence adversely impacts the world economy. By and large they result from increased productivity in developing nations, who are able to offset the loss of trade gains by banking the extra productivity. The developed world can’t offset the loss in the same way. The costs of imported goods rise relative to domestic goods and this amounts to a headwind against living standards. A tailwind turns into a headwind for economic growth, to be added to other headwinds such as adverse demographic changes.

These are, funnily enough, the problems of success. Globalisation has done a huge amount to advance human development, but we’ve reached the top of the escalator (leaving aside, for now, the issue of what happens to the remaining less developed economies, in Africa for example). Much the same can be said of developments to manufacturing technology. We must look in a different direction to make future advances.

That different direction may include market economics, and surely it includes a trade in ideas – but physical trade will play a lesser role. Restoration of the environment, a better appreciation of human psychological needs, and a rethink of public services will be the critical elements. We can’t look to the recent past as our guide.