“A sensible politcal debate” is surely an oxymoron. Politics is a battle of personal ambitions in which popular prejudices provide the most useable ammunition. If you catch two politicians having a sensible debate, it is away from public attention, about an issue with no real salience. Immigration is an issue of high political salience – and always has been, so we shouldn’t wonder that so little of what is said by politicians makes any sense in the round. But in the end effective policy needs to be based on reality, and a sensible debate is needed to tease that out. Immigration is a case in point.

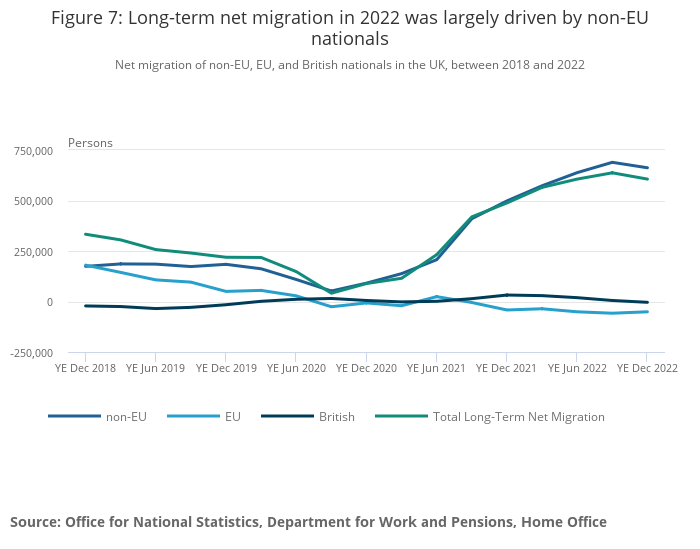

Immigration is currently moving up the political agenda. This is in spite of the fact that the leaders of none of the major political parties would rather talk about other things, and opinion polling shows that it is relatively low on the list of public concerns. That is because a group of conservative politicians see it as an opportunity to create mischief and further their political careers. The proximate cause are statistics that show immigration at record levels – though these statistics are highly unreliable as data collection is weak. The numbers have been driven up Ukrainian and Hong Kong refugees, the need for universities (and the country at large) to extract money from foreign students, and widespread labour shortages. Each of these causes seems to be understood by most of the public. So what’s the fuss?

There seem to be two main, mutually supporting strands raised by conservative politicians (with Labour leaders happy to echo them in their bid to show their conservative side): cultural and economic. Immigrants are usually culturally distinct (we can argue whether this is true of Australians…) – with different languages, religions and customs, and often maintain distinct communities. This is blamed for corroding traditional British culture. There is more than a tinge of racism here, though it is notable that many of the the leading public conservatives are themselves from ethnic minorities, and these ideas resonate with settled ethnic minority communities. There is plenty of irony here. Immigrants are keeping the churches full and often have conservative social values. One leading conservative politician claimed that immigration was leading to the declining number of people professing to be Christian, when the opposite is true. Of course this person (Nigel Farage) was seeking to exploit the trope that Western countries were being taken over by Muslims. It is easy for cosmopolitan liberals to laugh at all this, so many are the inconsistencies, but the message resonates well with older and less-educated people. There is a real conflict here between the cosmopolitans, typical of larger and more successful cities, and nativists, typical of more rural areas (though my own rural abode of Sussex is pretty cosmopolitan, it needs to be said) and smaller towns. If you take the Brexit referendum as an indictor of how the two outlooks divide (and it is more complicated than that) – then the country is split fairly much 50/50. It currently helps that, apart from the Ukrainains perhaps, the bulk of existing migrants tack onto communities that are already well established here – Indian, Chinese and Nigerian in particular.

Because of the clash of cultural attitudes, and the need to draw support from both sides, perhaps, most politicians choose to make their main arguments on immigration in terms of economics. It is said that excessive immigration is causing public services to be overstretched, exacerbating housing shortages pushing up property and rental costs, and pushing natives out of decent jobs, or at least pushing the level of pay down. The public services argument is the least serious. Public services are often amongst the most dependent on immigrant labour, and would be under even more strain if immigration was reduced. But a local influx can cause problems, and the system can be slower than it should be to adapt.

The argument on housing is more convincing. Pretty much everybody agrees that the supply of housing is failing to keep up with supply – though new housing developments seem to be popping up everywhere I travel to. After that vested interests take over, and it is very hard to get an objective take on things. One group of people blames restrictive planning laws which stop new homes being built, especially on rural and green belt land. The other side says that this would simply give developers carte-blanche to build lots of poor quality houses in ecologically vulnerable beauty spots, together with some high-end properties to act as stores of financial value for footloose foreigners. Clearly high levels of immigration make the problem worse – but the middle ground between developers’ search for an easy profit and nimbies trying to protect the value of their existing properties is largely uninhabited – and draws little serious, well-funded research. Economists tend to side unthinkingly with the developer lobby. Politicians may talk as if they are in the middle ground, but lack well thought-out policies that might do any good, and I’m practice end up at one of the extremes. Arguments over immigration just add grist to the mill. It is very hard to understand the implications of immigration strategies for housing without having a clearer idea of about housing strategy. But it clearly doesn’t help.

What about immigration and jobs? Recently changes as a result of Brexit caused a shortage of lorry drivers. Their pay shot up as a result; training schemes were upgraded, and more locals are now taking up the work. This is exactly how conservatives arguing for lower immigration say things should work. Using immigrant labour is an easy shortcut – but we would be better off we raised pay and brought more locals in to do the jobs. This is the vision conjured up by the Tory former leader Boris Johnson at the last election. But there’s a problem. This should mean that public sector wages need to be raised to help draw more people into the workforce. And yet the government wants to do the opposite: to use inflation to reduce real levels of public pay, and use the resulting surplus to fund tax cuts. They do this in the name of reducing inflation – but offer no long term solution to the problem of public sector pay. In fact a rebalancing of the economy in favour lower paid jobs will surely result in a degree of of inflation. It may also require taxes to be raised. The issues are quite complicated here, but a limited supply of labour creates something of a zero-sum game. Raising wages for the lower-paid is going to hurt somewhere.

Politicians sometimes talk about the need to improve training so that more locals can do jobs where we currently need immigrant labour. This clearly won’t work for things like fruit-picking, but is more convincing for doctors, nurses and social care workers. The problem here, as Stephen Bush of the FT points out, is that skilled labour is mobile, and the freshly trained workers will simply gravitate to where the best paid jobs are – which are often not in the UK. It is putting the cart before the horse. As the case with lorry drivers shows, if you fix the pay issue first, training is a much easier problem to solve.

The big, unspoken issue lying behind the fuss, is the country’s demographic development, with retired people taking up an increasing share of the population, while at the same time driving up demand for public services. Immigration is the obvious answer to this problem, though not in the long term, as the immigrants themselves will retire. If immigration is not the answer, then what is? Politicians place hope on increased productivity – but for a number of reasons this will not cut the mustard. The areas where productivity needs to advance to make the sort of impact required – in health care and social care services – seem to be those with the fewest practical proposals. Indeed, health and safety worries tend to push them in the opposite direction. Big investments in hi-tech factories may be a very good idea, but they will make little difference to economic growth overall, and impact the labour market even less.

The idea that the country should limit immigration is a perfectly respectable one. But it has a cost – we must pay more for critical services that are subject to labour shortages. That will involve a rebalancing of the economy and some painful economic adjustments. It would help if more people would talk about what this, exactly, means.