I haven’t commented on the Ukraine war since January, when the world was waiting for a new Russian offensive. That has come and gone, and now all the talk is of a Ukrainian offensive. First I want to look at the shape of things on the battlefield. Then I will take a step back and consider the situation strategically, before trying to probe how this war could end.

That Russian offensive turned out to be a damp squib. It was a series of attacks mainly in Donbas, and especially around the town of Bakhmut, the strategic value of which has been much argued over. The Russians made use of “human wave” attacks – a tactic with a long Russian history, but which led to massive casualties. Ukrainian casualties were quite heavy too, especially from relentless artillery fire. I was somehow expecting something more – the whole thing bespeaks of poor quality military leadership – apparently at all levels. What captured a lot of attention was politicking between Yevgeny Prigozhin and his Wagner Group mercenaries, and the regular military. Mr Prigozhin’s troops did much of the heavy lifting around Bakhmut, using poorly-trained recruits from prisons, and he sought to make political capital out of this. Gradually the Russian effort has fizzled out, as they moved to a more defensive stance, though they still seek to complete the conquest of Bakhmut.

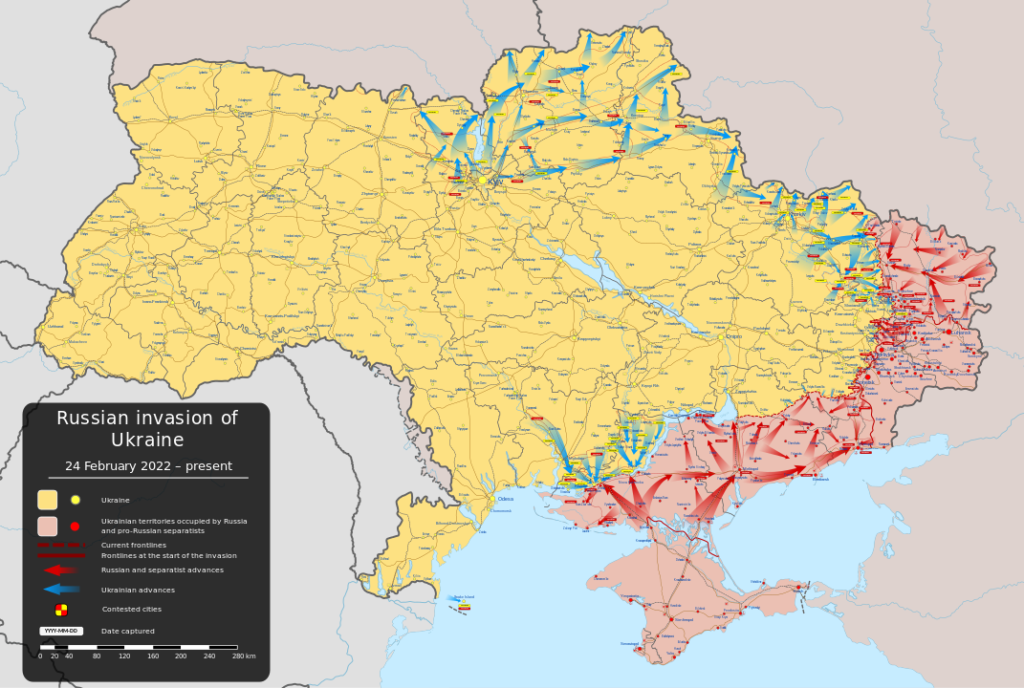

Which leads to the Ukrainian offensive. This is much talked about, including by Russian military commentators. Ukraine has been preparing a number of units for this task, and equipping them with advanced weapons supplied from the West. It is hard to tell what the real game is here. The Ukrainian leadership would clearly like to keep the Russians guessing as to where the blow will fall and when – but that is hard. The talk now is of whether the effort has already started, with some attacks north and south of Bakhmut. There is a game of bluff and double-bluff, and from this distance I can’t tell what is going on.

When it comes, the big question will be how tough and resilient will be the Russian troops on the receiving end. They are poorly trained and led, but their leadership is trying hard to steep them into the tough no-surrender traditions of the historic Russian military. If successful, even poorly-trained men will slow the Ukrainians down. Still, even though he Russian army is large by 21st Century standards, they have a lot of ground to cover, so they must be spread quite thinly. Another imponderable is ammunition supply. The Russian way of war is to use ammunition prolifically – and there are clear shortages. But ammunition supply is a major issue for Ukraine too. The Western powers’ ability to maintain stocks of ammunition for the weapons they are supplying is in question. Probably the reason for the regular waves of Russian missile and drone attacks is to run down Ukraine’s stocks of anti-aircraft munitions – especially since American intelligence leaks indicated that these were running low.

One area that Ukraine has been pressurising its allies on is the supply of advanced fighter aircraft like the American-made F-16 (though these aren’t top of the range weapons in the most advanced arsenals, they will out-perform the Soviet era equipment Ukraine has been using to date). The allies appear reluctant – as these aircraft require substantial logistical support, and any bases would become a natural Russian target that would be hard to move. The Economist points out that Sweden’s Viggen aircraft would be much more appropriate, as it doesn’t need big bases – but there aren’t enough of these around. A significant force of F-16s would undoubtedly give Ukraine more options, however, but they clearly cannot arrive before their offensive gets under way.

Which brings me to strategy. There is something rather curious about this war: the Russian don’t refer to it as a “Special Military Operation” for nothing: it is important to them to minimise its impact on the daily life of Russian citizens. This is a far cry from the total war idea we saw in the Second World War – but it is very much the way the Western powers have tried to conduct their wars, from Korea to Vietnam to Iraq. Ukraine is having to play along with this, and restrain their attacks on Russian territory, and even on Crimea, which is widely recognised as theirs. They have more to lose from an escalation. And so we have a paradox at the heart of the Russian strategy – the conflict is claimed to be an existential battle with the West for Russian values, and yet the Russian commitment to it is restrained. The Russians hesitate to mobilise further troops, or force their population to endure major shortages as more economic heft is devoted to the war. The Russian leadership has, in fact, been remarkably successful in insulating their public. But it limits any attempts to overwhelm Ukraine – and is ceding the initiative on the ground.

Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, apparently feels that he has long-term advantages. Ukraine is dependent on Western succour, and this cannot last indefinitely. The leading Republican presidential candidates in America, Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis, seem reluctant to maintain American commitment – and the presidential election is only next year. European commitment can be seen as a glass half-full or half-empty, like so much of what Europeans do. Meanwhile China might start to come through as an ally, providing vital logistical support. Furthermore there are questions about how the Western powers can keep the supply of munitions going in the long term – it is hard to ramp up production volumes. So the Russian strategy looks to be to weather the storm from the upcoming Ukrainian offensive, and then slowly take the initiative back, until America in particular wilts.

Will this work? It is rather of the nature of war that the leaders of each side tend to under-estimate their opponents – and both sides in this war have been guilty of that. I think Mr Putin is here. But neither should we underestimate his grip on power in Russia, and nor his ability to keep the Russian war effort going. All of which is a grim prospect.

How might things end? The signs are that Russia could settle for keeping most of their territorial gains. They are likely to choose to do this through a ceasefire, followed by a frozen conflict, of the sort already ongoing before the 2022 assault (or those in Georgia and Azerbaijan – or Korea). Of course there would be talks toward a longer term settlement, but these would get nowhere. The conflict might then be reignited later if the balance of power shifted. Ukraine’s ambiguous status would prevent it from entering NATO. This seems to be more or less the sort of resolution China wants to achieve.

It is obvious enough why the Ukrainian government wants to avoid this outcome. They would lose much territory permanently, and the threat of re-ignition of the conflict would be constant. And yet it is difficult to see that the war will end in any other way. The Russian regime cannot admit that the war is over and that they have lost. Even if Mr Putin is replaced, it is highly unlikely that any replacement will renounce his expansionist narrative. The regime is tapping into widespread popular beliefs. This means that Ukraine must retake as much territory as possible before a ceasefire is forced on them.

This would put a priority on territory south of the Dnieper river up to the Sea of Azov. This forms a land bridge between Russia and the Crimean peninsula. This is, naturally, where Russian defences appear to be thickest. As the offensive moves from advance to stalemate, the Ukrainian leadership will then come under huge pressure to settle for a ceasefire accompanied by peace talks.

Once we get to a ceasefire and move to a frozen conflict, the pace of changes slows. This can go in roughly two directions. The worst case scenario is that Russia follows North Korea, and is gripped by a totalitarian regime that is an economic failure, but where the regime’s grip is secure. The alternative is that we follow the Cold War, where the Russian leadership’s economic and other failings lead to a loss of confidence and political implosion… and ultimately a new settlement with the West. Ukraine, meanwhile, embraces the West and the European Union, and enjoys economic success as it rebuilds. Such rebuilding efforts usually surpass outside expectation – and the manner Ukraine’s military and civic success in beating off the Russians bodes well for its economic development, just as the Russian security elite’s tightening grip bodes ill for Russia’s.

But first this summer’s events will shape who controls the ground. Alas that means that there will be many thousands more deaths before we can approach some kind of resolution.

Let us grant that Russia has staying power for a ‘special military operation’ kept, as at present, to a level of commitment which does not involve the population in an all-out war effort; that Russia can probably defend this year quite a bit of the territory it has invaded over the last 15 months: and that the US congress will likely reign back the present level of US support. What then should Europe do? It seems to me that it should stay the course, because Russia is being such an immense nuisance to its interests. It is a major cause of refugees by thwarting Western efforts to stabilise the Middle East; it blocks the West’s UN resolutions; and it interferes with the elections of Western Countries.The refugees in particular are a major problem at present which is likely to get worse.

If Europe and Ukraine do stay the course, it not Russia’s medium term prospects bleak? Its GDP is relatively small; its population is a quarter of that of the EU plus the UK plus Ukraine; centralised states are not inventive ones, as the present war has already been demonstrating; where-as Europe has access not only to it own inventiveness, but also that of the USA, in providing Ukraine with weapons. Moreover , given the choice, people prefer to live in Western-style societies – as was demonstrated in the Communist satellites in 1990. So cannot Europe afford to back Ukraine with better weapons than the Russian ones, aiming say to enable Ukraine to recover the recover recently invaded territories and then perhaps have a frozen conflict for a while over Crimea . This would reduce Russia’s influence and might in the medium term lead to the West getting Russia to join with it, as was hoped in the 1990s.

That is an interesting thought. The problem is the Europeans’ lack of military heft, which applies to military logistics. Ukraine is currently dependent on the US. Having said that it is quite likely Europe could do a deal with a Republican administration to help finance continued US support. This could be portrayed as a political victory for the US by forcing Europe to take more responsibility for its security. That would certainly be in Europe’s interests, as you say. Russia could nevertheless limp on for a long time. The precedent of the Koreas is not encouraging.