In my last post but one I discussed how Britain’s politicians are in denial over the hard choices that need to be made over taxation – evidenced by a fatuous Autumn Financial Statement from the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the inadequate opposition response. Now The Resolution Foundation has published a new report: Ending Stagnation: a New Economic Strategy for Britain, based on a substantial amount of research, and again we are coming back to the growth problem.

Unfortunately I haven’t read this worthy and weighty contribution to the debate. It is nearly 300 pages long and describes itself as a “book”. Instead I have read the Executive Summary and some of the commentary, including from Torsten Bell, the Resolution Foundation’s Chief Executive, amongst other reviews. These leave me a bit confused, and clearly a lot of the devil (and perhaps some angels too) is in the detail. Given my substantial reading list, getting round to reading the detail will take some time.

Mr Bell has been trying to paint an optimistic picture – that Britain has the opportunity for catch up growth based on its weak performance: something that I have mentioned, amid my rather dismal assessment of longer term growth prospects. He points to two opportunities in particular: strengths in service industries which can be an engine of export growth, and the ability of Britain’s weaker regions to narrow the gap with the prosperous London and South East.

The point about services is an interesting one. It flows from two propositions that I agree with. The first is that manufacturing is yesterday’s story; it has become so efficient that there are few jobs in it, and besides there are saturation effects as the link between consuming quantities of stuff and improving wellbeing weakens. The second is that export industries are critical to most models of economic growth. Most successful economies in Europe and the developing world run trade surpluses. The US is an exception, but it is also an export powerhouse – it is just an import powerhouse too. The position of the US in the global economy is unique, however, and it doesn’t offer Britain any kind of hopeful model.

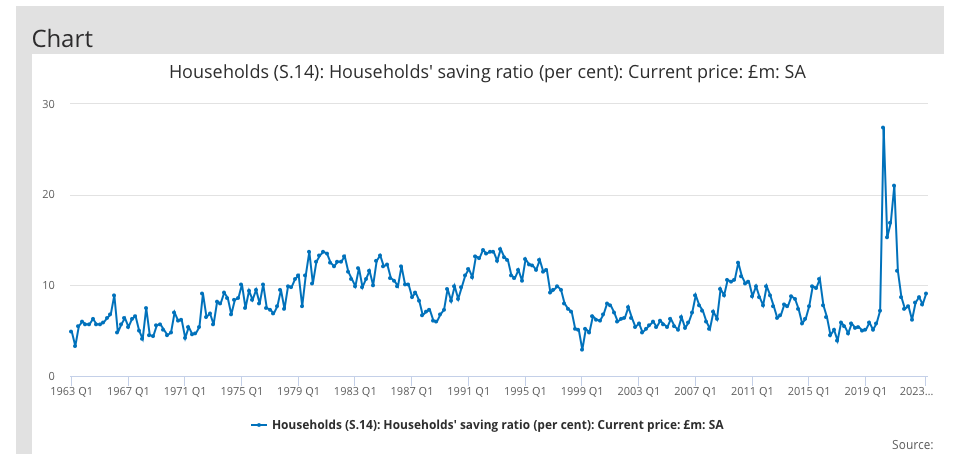

Why should exports be so important? That is a bit harder to answer. The explanation often advanced is that export industries are usually highly efficient (especially if they are not about mining and natural resources), partly because they have to be globally competitive, and partly, doubtless, because supplying things across borders requires a degree of efficiency anyway. There is doubtless a lot of truth to this. And this is linked to another truth, which is that exports and investment go together. This is in turn is linked to basic macroeconomic dynamics. A country with an export surplus consumes less than it earns – otherwise all the exports would be balanced by imports. And that usually means that such a country has high investment levels, as that surplus needs to be spent somewhere. That oversimplifies things quite a bit, of course, and disentangling cause and effect can be hard. But if Britain is going to play the catch-up game I am sure that it means three things that are very closely linked: better balanced trade (currently there is a 2.9% current account deficit – one of the largest amongst bigger economies, though America’s is close at 2.8%); greater levels of investment; and a higher rate of personal saving (currently 9.1%, actually relatively high compared to the pre-covid period, but still much lower than the EU average of 18.2%).

The first two parts of this trilogy are uncontroversial. Pretty much any commentary you care to read on the UK economy mentions the need for more investment, both private and public. People are less explicit about the need for more balanced trade. Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, before floating exchange rates and free capital flows, this used to be a matter of high political drama. Since then it has dropped from the conversation; Britain seemed to be doing just fine in spite of regular and large negative balances. But conversations about growth often turn to greater export volumes, and that implies more balanced trade. But surely something else is true: the country needs to import less if it is to save more and provide the funds for investment. And that means consuming less. There is a strikingly similar conversation to be had about tax. Higher public investment, and better quality public services, and a more adequate social safety net, imply higher taxes… and less consumption.

Looking at the graph of Britain’s savings rate over the last 70 years (above) it is hard not to see the supposedly economic golden years of new Labour, from about 2000 to the crisis of 2007-09, as a bit hollow: a consumption boom based on reduced savings levels. It was linked to a consistent current account deficit (the last surplus was in the mid-1990s). I have always thought this economic achievement was less than it appeared, driven as much of it was by the spurious profitability of the banking sector, which was reversed in the financial crisis. One important aspect of the decline of personal savings in this period was the reduction of corporate pension schemes. I witnessed this at first hand as a finance director in the first part of the 2000s, with presentations from consultants offering to reduce the costs and risks of pension schemes for employees. Final salary schemes were replaced with money-purchase ones, which almost always entailed a simultaneous reduction in contribution rates. This was sold as an advance for personal autonomy over the patronising ways of the past. In truth the potential liabilities associated with final salary schemes, or more correctly defined-benefit ones, were quite scary, and they gave employees who changed jobs a rough ride. Also the general decline in interest rates made those promises more expensive to keep. But now the collapse in pension funds as the source of UK business investment is much remarked on, though people tend to blame the post-crash flight to safety in pensions regulation; its roots are much deeper. Attempts to revive domestic business investment by the Chancellor look puny by comparison with the larger economic forces in play.

How might the savings rate be increased? The best way surely is for the current rise in interest rates to be sustained. This will deliver higher returns on new savings, even as it damages the capital value of past savings. There is a paradox here. It is often claimed that lower interest rates are required to stimulate business investment, but reducing the costs of finance. But the finance director in me says that cheap finance means poor-quality investment. There is nothing like a higher target rate for return on investment to focus minds on the best way to structure an investment project. I have seen it time and again.

Another problem with higher interest rates is that, all other things equal, it will drive up the exchange rate. This would make exports more expensive and imports cheaper – working against reducing the trade deficit. it would tend to make the country less attractive for foreign business investors. But part of the attraction of raising domestic savings is that it reduces the dependence on foreign capital, which is less reliable for a medium-sized economy like Britain’s. Many of Britain’s most successful businesses are foreign-owned and based on foreign investment. And yet, in spite of a relatively cheap pound, these foreigners have not invested much recently, especially since Brexit.

Unfortunately there is no guarantee that higher domestic savings would lead to more productive business investment. The old defined benefit pensions were a particularly effective channel for this purpose, and they are gone for good. More money could be pushed into domestic property – though some funding for this sector would be a good thing, so long as it just isn’t a matter pushing up land prices. Funds could be swept up by government debt, if budget deficits are not also brought under control. But buy and large a higher interest rate environment is more conducive to productive investment, rather than fuelling speculation. High interest rates are not good for the property market, which in current conditions is a good thing. Serious thought needs to be given to pension reform so that there is greater level of collective investment – as this is most likely to be channelled productively. There are examples from other countries of ways that this might be done (the Netherlands and Australia come to mind).

So my recipe for getting the British economy onto a healthier path includes higher taxes and higher interest rates. This is not going to be taken up by any political party – but parties in government might be forced into that route anyway. The Conservatives seem the least likely to do so – with their agenda of tax cuts and supporting property prices. My favoured option is for a Labour-Lib Dem coalition – which would require a hung parliament, and both parties having the stomach for a coalition. On present evidence neither proposition is looking likely. A large part of Britain’s lacklustre performance comes down to our prioritisation of personal consumption. Changing that is a hard road.

It is indeed difficult to see where the causality originates in all these interconnected variables – the savings ratio, investment, export surpluses, growth rates, interest rates and so on. However, for my money one causal factor is that a country’s service and manufacturing industries should be efficient and innovative, leading to an export surplus and opportunities to invest. The resulting extra demand in the economy from the trade surplus and investment will squeeze consumption if inflation is not to set in. But consumers may nevertheless experience prosperity due to higher growth from the investment, and also from competitive success in international markets supporting a higher exchange rate than otherwise and hence more favourable terms of trade. Factors making for efficient and innovative industry include high skills in the work force, a frank and cooperative flow of information between top management and others in a company, and an attractiveness to international companies with their vital stores of knowledge about ‘how to’ – all factors missing in post-brexit Britain.

Actually things are present in Britain if you know where to look. Just not enough. You have articulated the export-led prosperity story well. The trouble is that not everybody in the world can do it (or not unless the exports are entirely balanced by imports), and to many other countries have got here first, making it very hard to catch up. Thatcher started the process and Blair/Brown consolidated it.

“Another problem with higher interest rates is that, all other things equal, it will drive up the exchange rate.”

True. Our overseas partners will want to save more so their spare money will flow back into the UK.

“But part of the attraction of raising domestic savings is that it reduces the dependence on foreign capital”

It doesn’t though. Higher interest rates encourage everyone to save more and it doesn’t really matter where the savers live geographically. We can have more of both, or less of both, but not

more of one but less of the other – in the absence of capital exchange controls.

It is often said that the Government’s deficit is, to the penny, everyone else’s savings. Again it doesn’t really matter where “everyone else” lives.

So if you want everyone else to save more, and the Govt also to run a larger deficit, then raising interest rates is probably a good idea.

As always we should have a clear idea of what we are trying to achieve to avoid any unintended consequences!

Yes of course. What I should have said is that a trading surplus reduces dependence on foreign capital. But a trading surplus goes hand in hand with high saving, for the same reason that a it goes hand in hand with a government deficit. Japan is interesting (and extraordinary) because it combines a current account surplus (3.1%) with a government deficit (5.1%) – thanks to high domestic savings. It is not vulnerable to flighty foreign investors. Of course that’s also because the Bank of Japan buys up large quantities of government debt – but I think that’s easier if the current account is in surplus.

I think it does matter where people live, especially if you are running a smaller open economy (so not the US…) because currency risks enter the picture. If you can borrow freely abroad in your own currency then all well and good – but if people think the currency has a high risk of depreciation, then this can get a bit expensive.