Picture:Raphaël Thiémard from Belgium., CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

My last post was a bit gloomy – and indeed there is a lot to be gloomy about at the end of 2023. But you can overdo it, as amid the darkness there is hope. That hope does seem rather remote, but we must hold onto it.

What I want to reflect on today is something that I will call liberal capitalism, a system that is often referred to as liberal democracy – but I wish to emphasise that capitalism is at its heart. It is a system based on democracy, tolerance, respect for individual rights, a system of law and justice separated from political control, freedom of speech and news media, free commerce, and the private ownership of capital in a mixed economy. The system is often referred to as Western, but there is nothing inherently Western about it – and indeed Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have all found their own versions.

Liberal capitalism is under siege. The Chinese and Russian political leaderships in particular, having started an embrace of the system, are turning hostile. They point to the hypocrisy of Western governments and politicians, and resent the way that they, or we, espouse universal values and seek to undermine systems that are perceived to be corrupt or oppressive. Chinese leaders point to the chaotic ways and allegedly short-termist policies of democratic systems. Russian ones prefer to talk about the erosion of traditional values – by which they mean the advance of such things as gay rights, feminism and multiculturalism – although the Chinese leadership has similar views.

The Chinese and Russian leaderships are not alone; there is also an Islamist line of attack – though there is nothing inherently un-Islamic about liberal capitalism, once you have resolved the issue of debt and interest (where, incidentally, I have much sympathy with Islamic scholars – they have spotted a real moral problem). Iran is the leading state to push this line of thinking, as do a number of violent, and some non-violent, non-state movements. It differs from the Chinese and Russian critiques in propounding universal values, and very much seeking to interfere in the political systems of others (including those of Russia and China, as it happens). Beyond China, Russia and Iran, there are any number of states who reject critical aspects of the liberal capitalist systems, leading to criticism and worse from Western states.

And there is opposition to liberal capitalism from within liberal capitalist states. I frequently read from leftist authors that capitalism has failed, and needs to be replaced; others equate liberal capitalism with colonialism. And on the right populists say that the superstructure of democracy and the independent judiciary is simply a plot by liberal “elites” to impose their values on an unwilling majority. These populists have an admiration for the Russian system, with its espousal of traditional values, buttressed by a corrupt elite (though they aren’t explicit about the corruption, of course).

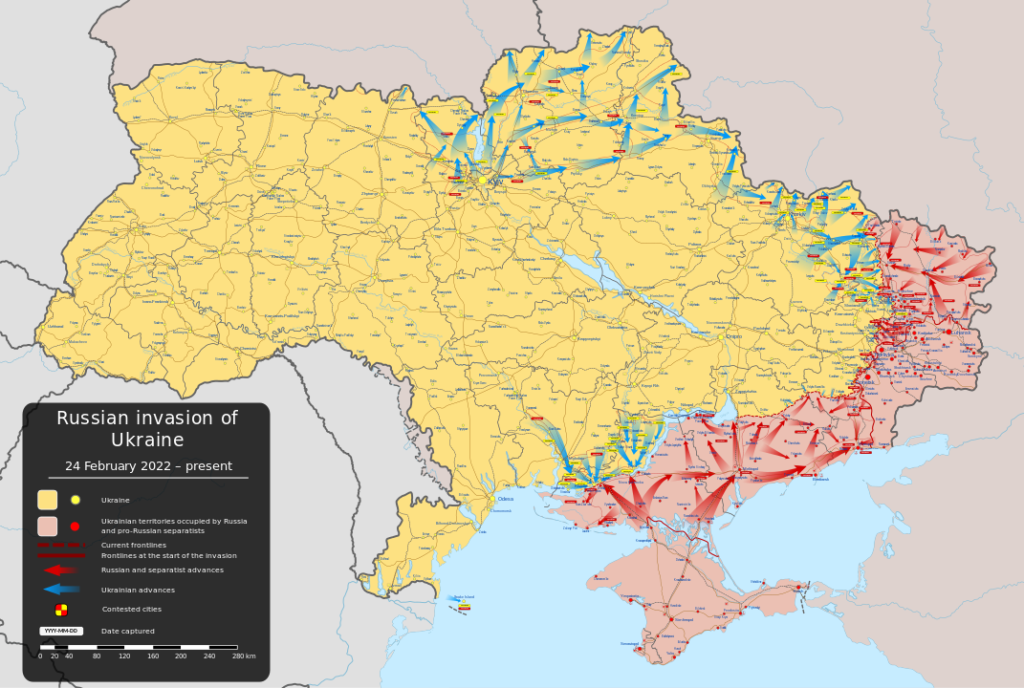

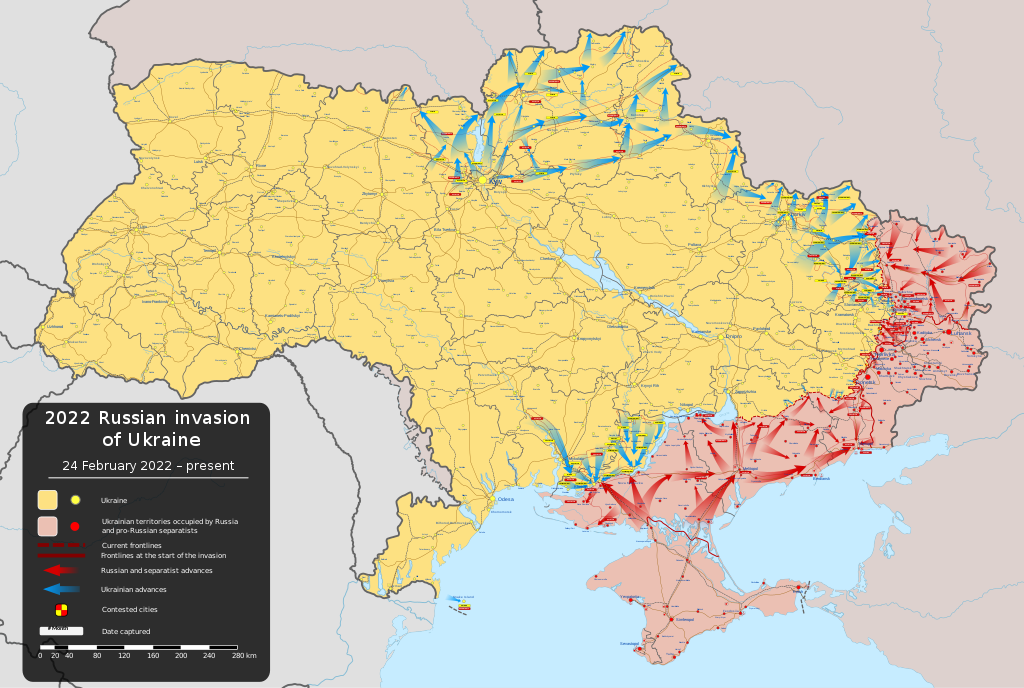

Often it seems as if the forces of opposition are winning. This partly stems from the way democracy and a free press works. Threats and danger make for more saleable publicity than optimism, which in any case reeks of complacency. Right up to the fall of the Berlin Wall you could read commentary that the USSR was winning the Cold War because Western democracies didn’t have the spine to resist. Even after the fall of the Wall, many westerners could not believe that the USSR was so rotten that it was fated to collapse under its own weight. But in 2023 there are indeed many worrying developments, and liberal capitalism seems to be on the retreat in many places. Across the world many accept Russia’s assault on Ukraine with a shrug; anti-democratic coups are becoming the norm in Africa; China’s diplomatic influence has grown immensely; populists (though not leftists) are doing well electorally in liberal capitalist systems.

But look again at the forces of darkness. What is it that they are offering? China and Russia celebrated the fall of the Western-backed regime in Afghanistan. But have they offered to replace the flow of Western aid? And as American interests come under threat in the Middle East, China and Russia are mere onlookers, their recent diplomatic advances proving to be weightless. Many states have welcomed the political neutrality of Chinese aid, but find this is linked to the use of Chinese contractors, and that Chinese creditors are less flexible than Western ones when things start to go awry. Debt forgiveness in developing countries has now become almost impossible due to Chinese obstruction. Russia extracts a heavy price for its aid, with ruling elites required to pay off the support of Russian thuggery with corrupt contracts for natural resources. Russia and Iran do not look like good places to live, though better than North Korea. China offers something a bit more appealing, but the costs are becoming increasingly apparent, as the state has to expend more and more effort in suppressing dissent, while managing a faltering economy and a shrinking workforce. And a closer examination of the Chinese system reveals striking degrees of racism, and at the fringes of its empire, such as in Inner Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang, it looks distinctly colonialist – not that you will hear Western leftists complaining.

Also on closer examination, ideas of political non-interference proposed by China and Russia turn out to be not quite what they seem. Russia has a very flexible idea of what the boundaries of its state actually are. The Chinese are slightly better, but not much. The idea of self-determination for the peoples of the empire’s further reaches is treasonous – even though these places were once outside its borders; the country has laid claim to the South China Sea without any internationally recognised legal basis. And there is Taiwan. Neither China nor Russia hesitates to interfere in other states’ affairs if they feel their interests can be advanced that way. Their covert operations are massive. For them it is simply enough to deny anything that is inconvenient. Western states may not be good at respecting the truth in their pronouncements; non-Western ones are much worse.

Liberal capitalism’s internal critics are no better. They are better at stoking feelings of victimhood than of offering constructive alternatives. Leftists may claim that capitalism has failed, but their alternative ideas are weak at best. On the few occasions they have been tried in practice, they have collapsed into economic weakness and political despotism, and, eventually to cronyism. The right evokes an unachievable past golden age; the closer they get to actual power, the weaker their ideas look.

Against all this the liberal capitalist system has much to offer. No other economic system has produced such serious advances in popular wellbeing, or driven back poverty so far. China’s highly impressive impressive economic achievements precisely follow its adoption of liberal capitalist policies. As it turns against those policies, its advances flag. Supporters of liberal capitalism say that you can’t cherry-pick aspects of it and expect to succeed in the long term. China has sought to contradict this by adopting the economic side of liberal capitalism, while standing against tis political one. This is at last being tested. Russia has also shown some economic success from its adoption of liberal capitalist economics, although the exploitation of natural resources has an added dimension there. It has a largely capitalist economic system, but it has institutionalised cronyism and corruption. This may prove attractive to other country’s ruling elites, such as in Victor Orban’s Hungary, but this system only works as long as there is enough meat on the carcass to go round. It does not maximise economic efficiency and is doomed to eventual decline.

Liberal capitalism does face important challenges though. Charges of hypocrisy made by its critics are often well-founded. But for these critics, or the state ones anyway, their point is that we are all hypocrites, so let us be openly cynical in the way we advance our interests; that is not a message of hope. They may complain that Western support for Israel is inconsistent with its attitude to Ukraine – but nobody else is offering more than token support to the Palestinians, who will receive more external aid from Western countries than they ever will from China, Russia or Iran – though the Gulf Arabs will hopefully contribute even more. The rationale for when Western states intervene militarily, or with military aid, and when they don’t is far from clear. The comparison of Ukraine with Palestine is a deeply flawed one; that with Iraq in 2003 is less so. The West’s universalist rhetoric is tying it in knots (non-Western liberal capitalists tend not to make this mistake). I believe this needs to be tempered with a proximity principle, which shows why Ukraine is different from Syria, say. Alas that invites many questions of definition.

There are more substantive challenges. One is economic. Liberal capitalism was once associated with high economic growth, but in the more developed countries this has come to an end. This is not a failure of the system, as some suggest, but a feature. Liberal capitalism delivers to its people what they want as revealed by their consumer and democratic choices. These choices now favour lower growth, and that is exactly what the system is delivering. The priority now is to advance wellbeing through the use of technology and scientific knowledge without this being tied to ever-increasing consumption. Liberal capitalism can do this, though its political leaders have for the most part failed to see how the game has changed. Environmental sustainability, including the need to be carbon-negative, is another, more widely recognised challenge. Migration and cultural integration is also widely recognised as an issue. In less developed countries adopting the system, law and order and the rise of gang culture is a further challenge for the restrained systems of law-enforcement associated with liberal capitalism.

But in the end people will recognise that liberal capitalism offers the only real path to achieving a better world – the sort of place in which most people want to live. Because they can’t deliver this, its opponents are weaker than they look – like the USSR in the Cold War.