Back in 2021 it had seemed impossible for Donald Trump to return to the White House. Even in 2022 it seemed that his brand was diminished – as candidates he endorsed did badly in Congressional elections. But we should have known better. For the first time in his political career, the man looks unstoppable. We must now think what many of us liberals had thought unthinkable: he will be President again.

Pretty much everybody I know regards the prospect of a repeat Trump presidency with horror, including a handful of Americans. Some Britons do like Trump, but most treat him as a bit of a joke – a caricature of the worst American stereotypes, and transparently narcissistic. This country has had enough of un-serious politicians after the chaotic period of Boris Johnson’s ministry, and his successors’ indulgence in gesture politics. It is one reason that Sir Keir Starmer’s popularity ratings are now high – seriousness is his most demonstrable virtue. You don’t have to be a liberal here in order to dislike Trump.

But it is clearly different in America. The first way that Mr Trump has been able to make a comeback is that he has fired up a supporter base that has enabled him to take over the Republican Party. He has made short work of his rivals, and any Republican law-maker that doesn’t pay homage to him will have their careers quickly terminated. Mr Trump has been able to forge a special bond with this supporters. He plays on their sense of grievance, and the feeling that the political establishment despises them (which they often do…). This seems is intuitive – I have called him a right-brained genius – following the once-fashionable idea that people are a product of a rational left brain and an emotional and instinctive right one. The irony is that this idea was promoted by liberal types to suggest that Western culture was excessively left-brained and destroying the world – and that the world needed more right-brained thinking. Alas this analysis turned out to be too left-brained.

The interesting thing about Mr Trump’s genius is that other conservative politicians have been unable to replicate it. Ultimately they are too calculating and they can’t hide it, and that undermines their authenticity. That fate has befallen Florida Governor Ron De Santis, once billed as being more dangerous, because more rational. We will have to see how Mr Trump’s Vice Presidential pick JD Vance works out. He is clearly a calculating man, but he gets much closer to his boss’s rhetoric than Mr De Santis did – and his empathy with white working class Americans is authentic.

The second reason for Mr Trump’s comeback lies with the current President, Joe Biden. He did well to beat Mr Trump in 2020 – and he has been highly effective in office. Too effective, perhaps. A narrow victory in a campaign that was mainly about the fitness for office of his opponent was not a mandate for many of the radical measures that he brought forward. There were two particular problems. The first was that inflation got out of hand on his watch. Some of the blame may lie with the fiscal generosity of his predecessor, and some arose from international events – but Mr Biden threw in plenty of fiscal generosity of his own. Inflation is now back under control (apparently) but it has left deep scars in its wake, notably with interest rates still high, and petrol prices over 20% higher than in his first year of office. Mr Biden’s supporters like to paint a rosy picture of their man’s economic achievements – but no amount of aggregrate economic statistics can mitigate the pain that many American people have gone through. The second major problem is the chaotic scenes on the border. Now I haven’t been following that particular issue closely, and it is clearly being hyped up by the Republicans – but there does seem to have been a lack of focus by the Biden administration in its attempts to play a number of competing interests.

And then there was the question of Mr Biden’s lack of physical fitness for office. His disastrous debate performance with Mr trump only confirmed what many people had suspected. As I write, he has now thankfully bowed out – but only after an obstinate period of denial. His likely replacement candidate is the Vice President, Kamala Harris. She doesn’t get a very good press (though how justified that is I find hard to assess). My feeling is that she would do a better job than Biden of mobilising the Democrat base, especially younger voters, but will struggle with neutral voters. But the Democrats campaign has lost momentum, and will need to be completely reset.

I don’t think Mr Trump’s survival of the assassination attempt will make more than a marginal difference. It gave him some momentum at a useful time, which doubtless helped bring some donations in. But he and his party reverted to type so quickly afterwards that surely few voters will be swayed.

Mr Trump still has those two big points in his favour: the economy and the border. For some reason many American voters, even those who are otherwise sceptical of Mr Trump, think that he is a better bet for managing both issues than whoever the Democrats throw up. In the case of the economy, that’s a bit bizarre. He plans to raise prices for ordinary Americans by imposing tariffs, while reducing taxes for the better off by adding to the national debt. Reducing immigration, if he succeeds, may make things worse by raising inflation – though it could help lower-paid workers. Still, the idea that a businessman is well-placed to manage the economy a strong one in America. And if Mr Trump’s record as a businessman is a flawed one, years of starring in The Apprentice have clearly impressed many Americans.

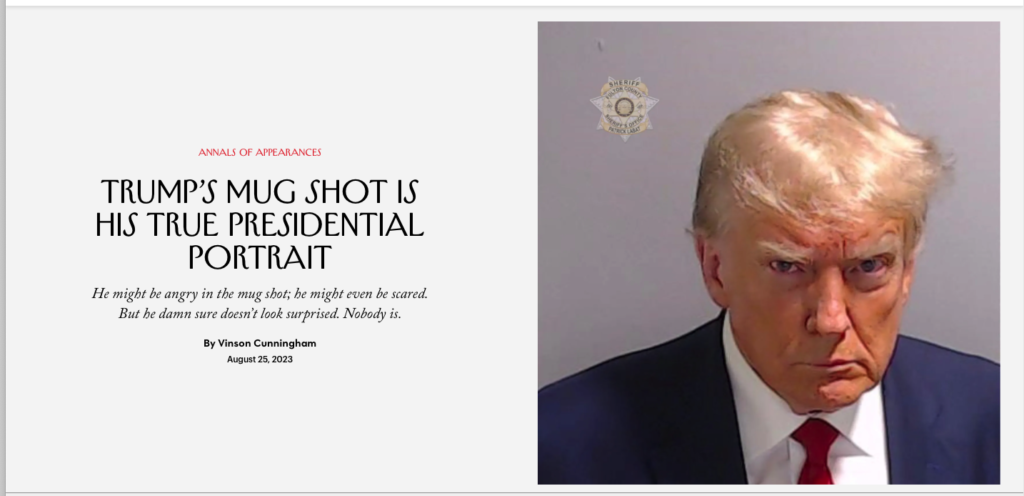

And as for the threat Mr Trump poses to American institutions, many Americans clearly don’t think he will be that bad in practice – and perhaps those institutions have been corrupted anyway. The only criminal convictions that Mr Trump has so far suffered were from a distinctly dubious case legally, giving some substance to Mr Trump’s accusations of “lawfare” against him. Other cases may be stronger but the American judiciary has played along with his efforts to kick them into the long grass. Mr Trump has never made himself out to be a saint, even if he sometimes claims to be an instrument of God.

So what are the consequences for us Europeans if Mr Trump succeeds? The most serious is the war in Ukraine. Most European leaders want wear the Russians down, and force them to conclude the war on terms that they cannot paint as victory – and so weakening their threat. They hope that Mr Trump can be manoeuvred into supporting this – but they know it is unlikely. More likely is that he will force Ukraine into a ceasefire. Russia is then likely to regroup and rearm – although it is possible that the enormous cost of the war will start to rebound on Vladimir Putin’s regime. The European powers will have to reorganise their defences, and reduce their dependence on US weaponry.

Economically the main threat is Mr Trump’s proposed tariff regime – but the main economic damage is likely to be wrought on the Americans themselves, and then their neighbours in the Americas and Asia. But it is unlikely to help Europe’s struggling economies – hastening the awkward political choices that permanent low growth will entail.

A difficult four years beckon. It may not come to that, of course. The last month or so have already shown how fast politics can move. Mr Trump seems to have taken his recent successes as as justifying his continued focus on his base – rather than softening his image to appeal to uncommitted votes. If his opponents can succeed in making the threat of a Trump regime look less abstract – by focusing on concrete issues like abortion, rather abstract ones like “democracy” and “the rule of law”, and if their candidate looks properly presidential, more sceptical voters can be persuaded to vote him down. Perhaps, even, he will go too far and look start looking more dangerously deranged, even to some of his erstwhile supporters. We have been hoping for that for eight years, though, and nothing he does seems to faze his base.

Americans will do what Americans will do. We in Europe will just have to live with whatever they choose to do. That’s democracy, I’m afraid.

Postscript: 23 July

The news that Joe Biden was withdrawing broke while I was finishing the article. Anxious to publish, I edited it without changing the overall thrust. But the whole dynamic of the contest seems to have changed. Kamala Harris has launched her campaign built up real momentum – it looks as if she will be chosen without contest. The Trump campaign seems to have been wrong-footed. They have no shortage of attack lines on Ms Harris, whom they despise as much as her boss. But the main ones look weaker than the focus on mr Biden’s capacity, while the Democrats have some attack opportunities of their own: capacity issues can be turned back on Trump, and maybe they will even get a chance to attack some of Mr Trump’s policies – like his disastrous looking economic ideas. Alas Ms Harris’s early attack lines seem to focus on Mr Trump’s criminality and lack of moral fibre. That’s old news and won’t sway many, surely. Matt Goodwin, who had been predicting a Trump landslide, meanwhile rushed out an article suggesting that Ms Harris is an even more hopeless candidate than Mr Biden.

It will be a couple of weeks before we see if Ms Harris is making a serious impact on Mr Tump’s lead. American voters have a way of bringing me down to earth, so my wiser self is saying that the main thrust of my article still stands – even if my optimistic self thinks that the spring in the step that Ms Harris is showing must have some sort of positive effect.