Yesterdays’ Guardian carried an article entitled Apocalypse now: has the next giant financial crash already begun? by Paul Mason, who is Channel 4’s economics editor. The same paper carried an article last week by David Graeber: Britain is heading for another 2008 crash: here’s why. So it’s clearly becoming fashionable for left wing types to start spreading stories of doom. Could they be right?

Mr Graeber is not a professional economist (neither am I, I should make clear); he’s an anthropologist, in fact. He has written engagingly on financial matters though, notably his book Debt: the First 5,000 years. His enthusiasm is for the big picture and the global explanation. I found his book a huge let-down because he was incapable of analysing more recent financial events at any level below sweeping generalisation.

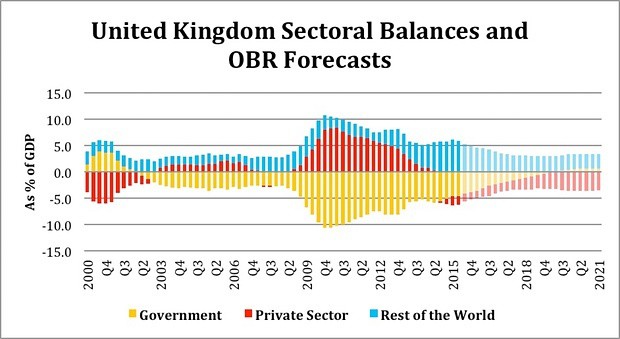

And so it is this time. His central argument is that enthusiasm for governments to cut their financial deficits means that private debt, at less affordable rates of interest, will pile up. The key strand of evidence is this graph, which shows public, private and external deficits:

He notes that it is symmetric, because it is based on an accounting identity. So, if the external balance is constant, which it roughly has been, any reduction in public deficit must be matched by an increase in private deficit. Ergo, we are simply swapping public debt for private debt. And since, as everybody knows, the crash of 2008 came about because of excessive private debt, another one is inevitable. He calls this the Peter-Paul principle (ie. robbing Peter to pay Paul).

Oh dear! It’s hard to know where to begin. As anybody with an understanding of mathematics will tell you, accounting identities don’t tell you as much as you might think. They are tautologies: you can’t use them to predict anything useful about the world. I remember, back in the 1980s, another accounting identity, this time on money, growth and inflation, getting people into trouble, as monetarists used it to “prove” that inflation and growth depended on money supply. Alas all it showed was how uselessly elastic are the concepts of money supply and velocity of circulation. A moment’s thought tells you that Mr Graeber’s argument must be flawed. He is suggesting that the amount of debt in the economy remains fixed – and yet it clearly goes up and down. Actually, the amount of debt is fixed – it is a net of zero! For every debtor there is a creditor; gross debt, however, must be independent of the sizes of the sectoral balances. The Peter-Paul principle is not the great taboo of economics as Mr Graeber suggests. It just doesn’ tell you very much. Not nothing, as the FT’s economics writer Martin Wolf, has shown – but it has taken him in a different direction. He suggests that if government austerity is not matched by extra private sector spending, the economy will shrink. An altogether more subtle point.

Mr Mason’s line of argument is sounder, in that it is based on more factual evidence rather than airy assertions. His line of argument is that aggregate debt has continued to rise, but the world economy has stalled, so that debt will be unrepayable, and so there will be a financial crisis. But this is still lightweight fare, based on aggregated data, which may be unreliable, and not on the specifics of who owes what to whom. The problem is that the world financial system is a very complex thing. It very hard to attribute cause and effect – or rather it is all too easy, it is just impossible to prove that you are right. The financial crash of 2007/2008 came about with the convergence of a number of things, of which the reckless build-up of private sector debt was only one (rising oil and food prices, reckless use of off-balance sheet finance by banks, persistent trade surpluses from China and oil states, a false sense of security from central banks – to name but a few).

One thing we can say is that the world in 2015 is very different from that of 2007, when the last crisis started. It is commonplace in left-wing circles to suggest that nothing has changed in the world of international banking since the crash. Well some banks are making money again, and some bankers are taking outrageous bonuses. But there are many fewer of them; there is much less profit sloshing around. The banks have been forced by regulation and bitter experience to be more prudent. Off-balance sheet finance, at the heart of the 2007 crisis, has been drastically reined in. And the world financial situation is very different, with low oil and commodity prices, a fading China, and the US fast becoming self-sufficient in hydrocarbons.

But that may not offer us much reassurance. We may not be heading for another 2007/2008 but we could still be heading for something nasty. There are four things that could be a sign of trouble:

- There are asset bubbles in some places. What is referred to as “emerging market” assets are the most spoken of: debt, shares and property located in China and various parts of the developing world. But there are others: London property and US shares come to mind. Some suggest that developed government bonds are in a similar bubble, as their prices are historically high, but Japan has shown that these prices can stay high for a very long time indeed.

- Central banks are running with ultra low interest rates, meaning that the main arm of monetary policy is not available. Quantitative Easing (QE) is problematic. This leaves them without the firepower to deal with a crisis as it emerges – or so many people think. In fact the dynamics of monetary policy have moved well beyond textbook theories about money supply and inflation expectations, leaving us unable to understand how things work.

- The maturing of China and the rise of shale oil and gas in the US have changed world financial and trade dynamics fundamentally from the pattern of the last two decades. I suspect the new pattern is more stable than the old one in the long run – but any such change tends to cause dislocation. It may, for example, become much more difficult for many countries, including Britain, to finance their deficits (the blue bit in Mr Graeber’s graph could shrink).

- International politics has become more fractious, making international deals more difficult to do. And populists from left and right are making it harder for governments to intervene to stabilise financial markets – often portrayed as bailing out bankers at the expense of ordinary taxpayers. That will make any future banking crisis harder to manage.

So I share some of Mr Hunt’s and Mr Graeber’s worries. I have my own airy narrative. Since the the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates and gold underpinning was broken in the 1970s, by President Nixon who needed to fund the Vietnam war without raising taxes, the world has been addicted to an increasing cycle of debt. Some of this debt might be regarded as lubrication for the wheels of capitalism. But also there seems to be a bit of Ponzi scheme about it, with debt being repaid by the issue of yet more debt, rather than through substantive economic advance. In the long run, that cannot be stable. And yet it may take a long while yet before the trouble starts to show up.