Picture: By AgnosticPreachersKid – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6282818

The more people pop up to say that the situation in financial markets is not like 2008, when the Great Financial Crisis got going, the more we will worry. But while a crisis like that of 2008-10 looks unlikely, a prolonged period of wealth-destruction is in prospect.

The current bout of nerves comes from the collapse of two mid-sized American banks, and from a globally big one: Credit Suisse. Technically Credit Suisse hasn’t gone bust – it was taken over by Swiss rival UBS. But shareholders were bought out very cheaply, and some bondholders were wiped out in a move that has raised a lot of eyebrows. This follows a period of tightening monetary policy, responding to a period of inflation – after a prolonged boom based on very low interest rates. There are many parallels here with 2008. But the differences are striking too.

It’s worth taking a deep breath, stepping back, and trying to get a broad view of what is happening. At issue is the financial system – the world of money, rather than the “real” world of things and services – though there is quite an element of the real directly tied up in finance, which is a substantial employer in many economies. Money is a means to an end, and not an end in itself – in principle anyway. Because of this, economists, especially the macro sort, tend to ignore it, or treat it in a very cursory way with very basic models for money supply. And yet money is essential to the modern way of life; we can do little without it. If the financial system seizes up, disaster strikes. The episode that looms most over economists is the Great Depression of the 1930s, when some little local difficulties within the financial system were allowed to explode, causing mass unemployment. In a depression, lots of people want to work, but can’t; and lots of people want to buy goods and services that employ people, and can’t either. It is a colossal social waste – and one that in the 1930s fed into racism, fascism and ultimately war and genocide. The financial system matters.

At the centre of the financial system are banks. In the days of Henry VIII the monetary system was controlled completely by the state, which had a monopoly on minting coins – and the state has always played a central role in the financial system. But these days money means bank accounts – the role of notes and coins is negligible. Because of their critical role, banks are heavily regulated, with a central bank, accountable to the state, playing a keystone role. Banks provide access to money, but what do they do with it? They can just park the money with the central bank, but they will make no profits that way. So they find various ways of lending it out – further, they may create money through their lending. They make loans directly to members of the public and businesses and to governments, sometimes on a short-term basis, sometimes for terms of many years. This creates a source of instability – if the the public withdraw their deposits, the banks may not be able to liquidate their loans fast enough to give them their money back. But this “maturity transformation” is generally profitable, and it is at the heart of a healthy economy, which allows resources owned by people that have too much to be used by those that have too little.

So far, so good. This is as far as classical economists got. Interest rates are set by a process of supply and demand between lenders and borrowers, spiced up by credit risk. More modern economists then added in a role for government/central bank intervention – monetary policy. By one means or another the government could tighten or loosen monetary conditions, mainly through setting interest rates, or through “quantitative easing” (QE) – the creation of money by the central bank buying bonds through its reserves. In many accounts monetary policy brings back the idea that the government/central bank controls money like Henry VIII and the Royal Mint. The process of QE is often referred to as “printing money”. This conjures up a happy picture of a world of governments, consumers and businesses buying things with banknotes, with banks making loans to cover investments in houses or industrial machinery, or to smooth ordinary cashflow fluctuations of businesses and the public. It is at least easy to visualise this world, but, alas, too many people who should know better seem to get stuck in it.

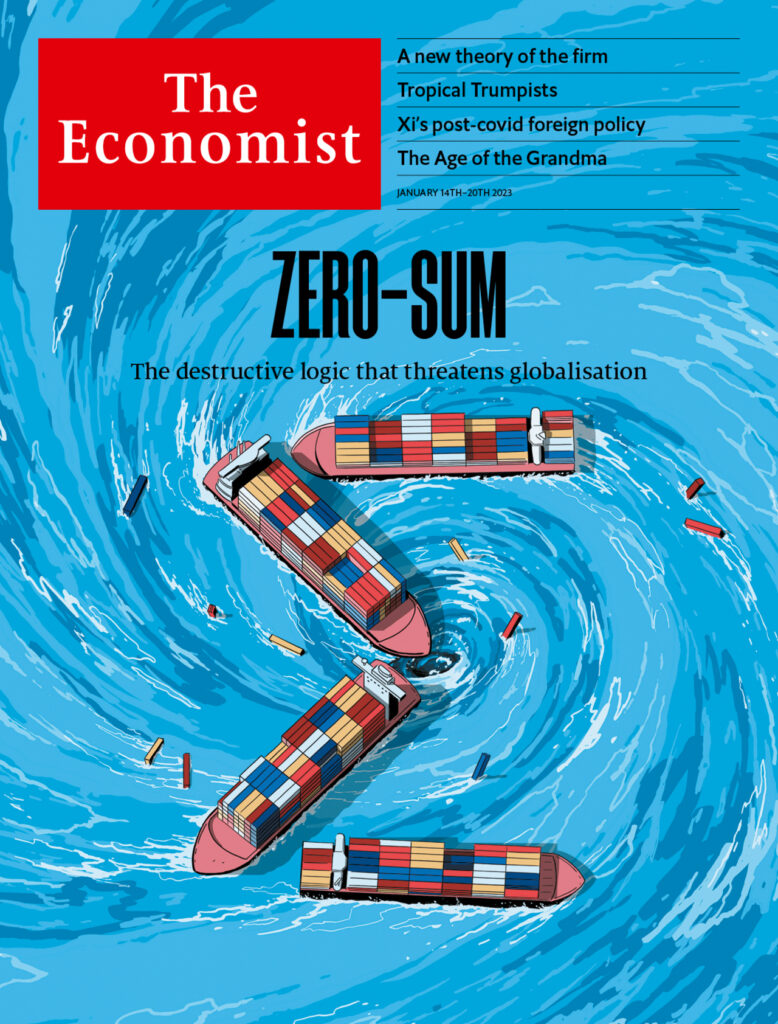

The trouble is that we don’t use banknotes any more. And banks lend to a range of financial intermediaries rather than to “real” people and businesses; businesses and governments don’t borrow directly from banks but via these intermediaries, often through tradable instruments – “securities”. This creates the modern financial system, and instead of being a simple machine for the transmission of funds from “real” lenders to “real” borrowers it becomes a merry-go-round of speculation fuelled by the chance to make money from trading securities. Money becomes an end in itself, rather than mere lubricant. One spectacular example of this are fans of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, touted as alternatives to “fiat money” created by central banks. They meet scepticism with the rejoinder “Have fun staying poor”. The point for them is to make money as intermediaries, not facilitate financial transactions. The money merry-go-round becomes a complex frenzy when monetary conditions are loose – when banks have more deposits than they know what to do with, either because there is a lack of serious lending opportunities, or because of “liquidity risk” – the risk that depositors will suddenly withdraw their deposits. At this point banks seek out opportunities for short-term speculations based on securities or short-term loans to financial intermediaries.

This was the situation in the run-up to 2008. Monetary conditions had been very loose. The narrative on why this was so varies. Many of a libertarian bent blame irresponsible monetary policy by the developed world central banks trying to fight deflation while asset prices were in a bubble. This was through low interest rates – only in Japan was there serious QE. Others point to the entry of China into the world trading and financial system with its huge excess saving. It brought in vast quantities of funds from its exports, and only used a proportion of these to buy imports, depositing a surplus of money in developed country financial markets. An oil price spike added to this with oil producers generating a similar financial surplus. Banks then had the headache (though mostly they thought of it as an opportunity rather than a problem) of where to put this surplus money and how to make a profit. Quite a lot of money went into sub-prime lending in the US property market. German banks, and others, happily lent money to the Greek government, which had entered the Euro and was fiddling its financial statistics. There was a frenzy of securitisation as banks sought to evade their regulatory straitjackets. It was like picking up pennies from in front of a steamroller. One thing I find striking from reading up my observations at the time was how much “risk management” featured in the jargon of bank professionals. They gave the impression that they had sophisticated risk models which meant that the massive profits they were making were simply the result of increased global productivity from the more efficient use of resources. There are still commentators that look back at the statistics of the mid-noughties and ask why productivity growth has slowed since then – insert pet theory here. It was a work of fiction – the trend in lost productivity growth in the developed world goes way back to way before the financial crash. Massive amounts were being lent off bank balance sheets supposedly to long-term investors like insurance companies. In fact the money was going round in circles amongst thinly capitalised intermediaries which often came back to haunt the banks themselves.

It couldn’t go on forever. Central banks increasingly felt they had to do something about loose financial conditions, especially as that oil price spike was causing headline inflation. In early 2007 the US sub-prime market started to show strain. Then in August 2007 the financial system broke when the interbank market – banks lending to each other to manage daily fluctuations – froze over. The complexity of financial securities meant that nobody knew who owed what to whom. I wrote this in September:

The ship has hit a reef below the waterline. There isn’t much visible sign at first; the ship slows down; it has a slight list, perhaps. But the crew looks worried even as the captain voices reassuring words to the passengers. Will the watertight compartments limit the damage until the ship makes it to port for repairs?

The ship limped on for more than a year, as market professionals and commentators went through the process of denial and then attempted to negotiate with their fate. And then the collapse of Lehman Brothers in October 2008 created a free fall. If governments had not indulged in massive bailouts of the system, the 1930s might have been repeated with institutions essential to our way of life going down. Alas that meant many undeserving people made out like bandits. The crisis kept going for two or more years, with the drama moving to the Eurozone in 2009.

So how do things compare in 2023? We are similarly in a period of monetary tightening following period of very loose policy, this time featuring the heavy use of QE in every major developed country market. Things were loose before the Covid pandemic struck in 2020, but this stayed the hands of central bankers, and unleashed a flood of fiscal intervention by the government to offset the effects of lockdowns as well as the direct impact of the disease. And then Russia started a war with Ukraine which completely disrupted the markets for oil and natural gas, forcing yet more fiscal interventions. This loose policy similarly unleashed a riot of financial speculation. But it is different this time. Banks are better regulated, though regulation of mid-sized banks in the US is still too light. There seems to be a lot less off-balance sheet lending. Paradoxically it is good thing that banks don’t tout sophisticated risk management these days – in 2007 this was justification of excessive risk. But inflation is much higher, and nominal interest rates have gone up much more, with big losses on government (and other) bonds that was not evident in 2007-08. This played a critical role in the demise of Silicon Valley Bank. Others presumably have similar exposures. There may be no substantial sub-prime market in the US, but many are worried about US commercial property lending.

And then there is the madness of cryptocurrency. I have not written much on this craze of the last few years. It is such deep, multi-layered nonsense that I couldn’t bring myself to take it seriously enough to write about it. The problem is that more respectable institutions started to take the phenomenon seriously and lent money to facilitate speculation. One of the biggest blots against current British prime minister and former Chancellor Rishi Sunak is that he wanted to make Britain a crypto hub. This is going predictably badly – an idea billed as an escape from the the tyranny of fiat money turns out to be even more dependant on fiat than fiat money itself. I understand that it contributed to both US bank collapses.

But the biggest difference between now and 2008 is that in 2023 we are in the shadow of the Great Financial Crisis, which remains in recent memory to those in charge. This is evident in the extraordinary level of intervention by the US Federal Reserve, in effect guaranteeing all bank deposits, even those outside the scope of deposit insurance. This has prevented such spectacular events as the freezing of the interbank market which led to my holed below the waterline image. A more apt image is the one conjured up by FT columnist Megan Greene: Schrödinger’s cat. We don’t know whether the system is stable or not – so it is both at once.

The striking thing is that with each crisis in the financial system the power of the central banks seems to grow. At the start of the 20th century the Americans didn’t even think they needed a central bank. Now the west seems to be converging with communist China in the use of both formal and informal state power. But power does not necessarily mean control, and the Federal Reserve especially is confronted with a series of very difficult choices. Inflation remains rampant but the banking system is fragile.

As I reflect on this the more it seems to me that the modern banking system is not fit for purpose. Steadily essential parts of the system are being nationalised. We are slowly moving to a system whereby deposits are in effect placed with the central bank – something which is happening rather rapidly in the US as the Federal Reserve gives support to money market funds. How, then, do banks fund loans? This is a role that central banks are ill-equipped to perform and should not be nationalised beyond a few specialist agencies. I guess they will need to provide longer term investment products – but the transition is bound to create casualties – and destabilise the banking system.

For now though we must expect this period of wealth-destruction to continue. Bank deposits may be safe, but inflation is eating their value away, as the prospect of positive real interests diminishes. Bond markets are undermined by the cessation and reversal of QE. Share markets need a growing economy. A weakened financial system will undermine property prices. And yet unemployment is low, minimum wages are in place and there are strong social safety nets. It is, surely, the wealthy that are being squeezed. That is not a bad thing.