The Liberal Democrat Treasury Secretary Danny Alexander’s place in history is assured. He is a member of the “quad” that sets the coalition government’s agenda, along with the Lib Dem Leader and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, the Prime Minister David Cameron and the Chancellor George Osborne (with whom he is pictured here). But recently there was a revealing kerfuffle, when the Lib Dems named their election “shadow cabinet” with him as the Treasury spokesman. Shouldn’t it be the more senior Vince Cable, people asked? Many Lib Dem activists fell for the bait and were suitably outraged. In fact this was a non-story – the shadow cabinet simply reflected current ministerial responsibilities with the gaps filled in. But if anybody had doubted Mr Alexander’s weak reputation, the response to the story proved it.

in history is assured. He is a member of the “quad” that sets the coalition government’s agenda, along with the Lib Dem Leader and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, the Prime Minister David Cameron and the Chancellor George Osborne (with whom he is pictured here). But recently there was a revealing kerfuffle, when the Lib Dems named their election “shadow cabinet” with him as the Treasury spokesman. Shouldn’t it be the more senior Vince Cable, people asked? Many Lib Dem activists fell for the bait and were suitably outraged. In fact this was a non-story – the shadow cabinet simply reflected current ministerial responsibilities with the gaps filled in. But if anybody had doubted Mr Alexander’s weak reputation, the response to the story proved it.

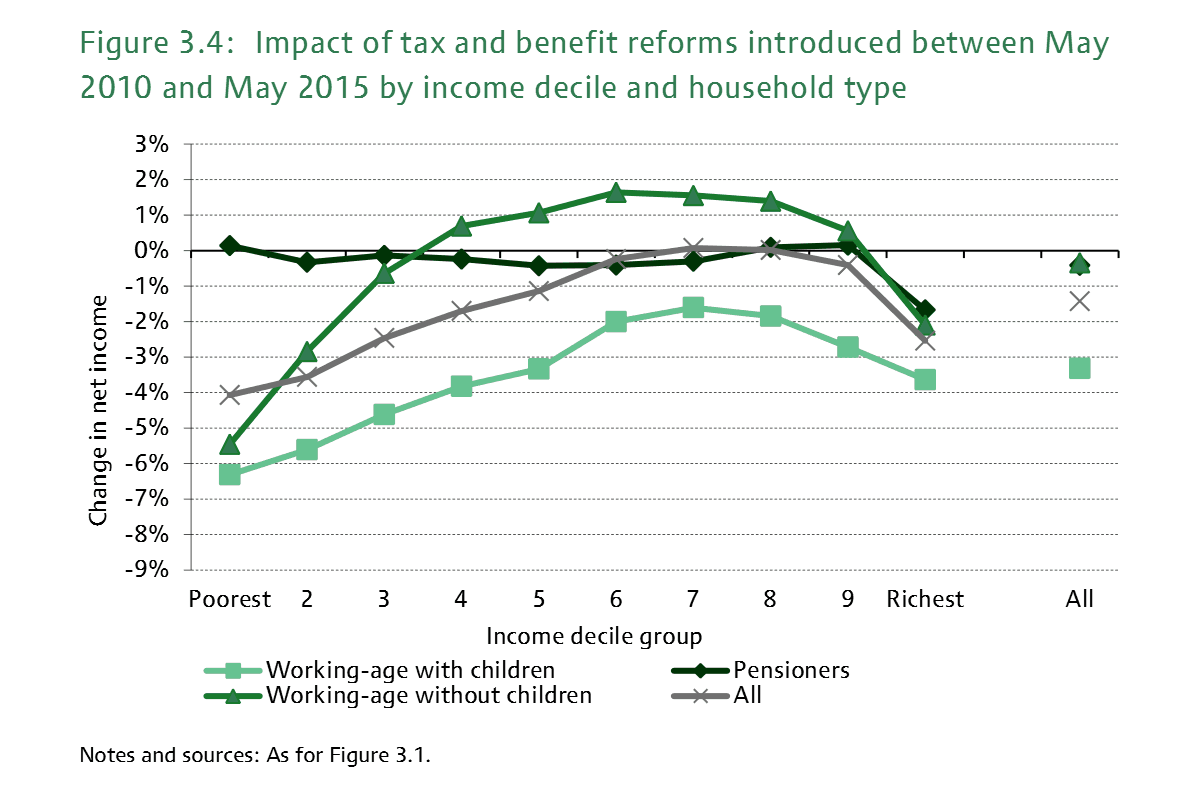

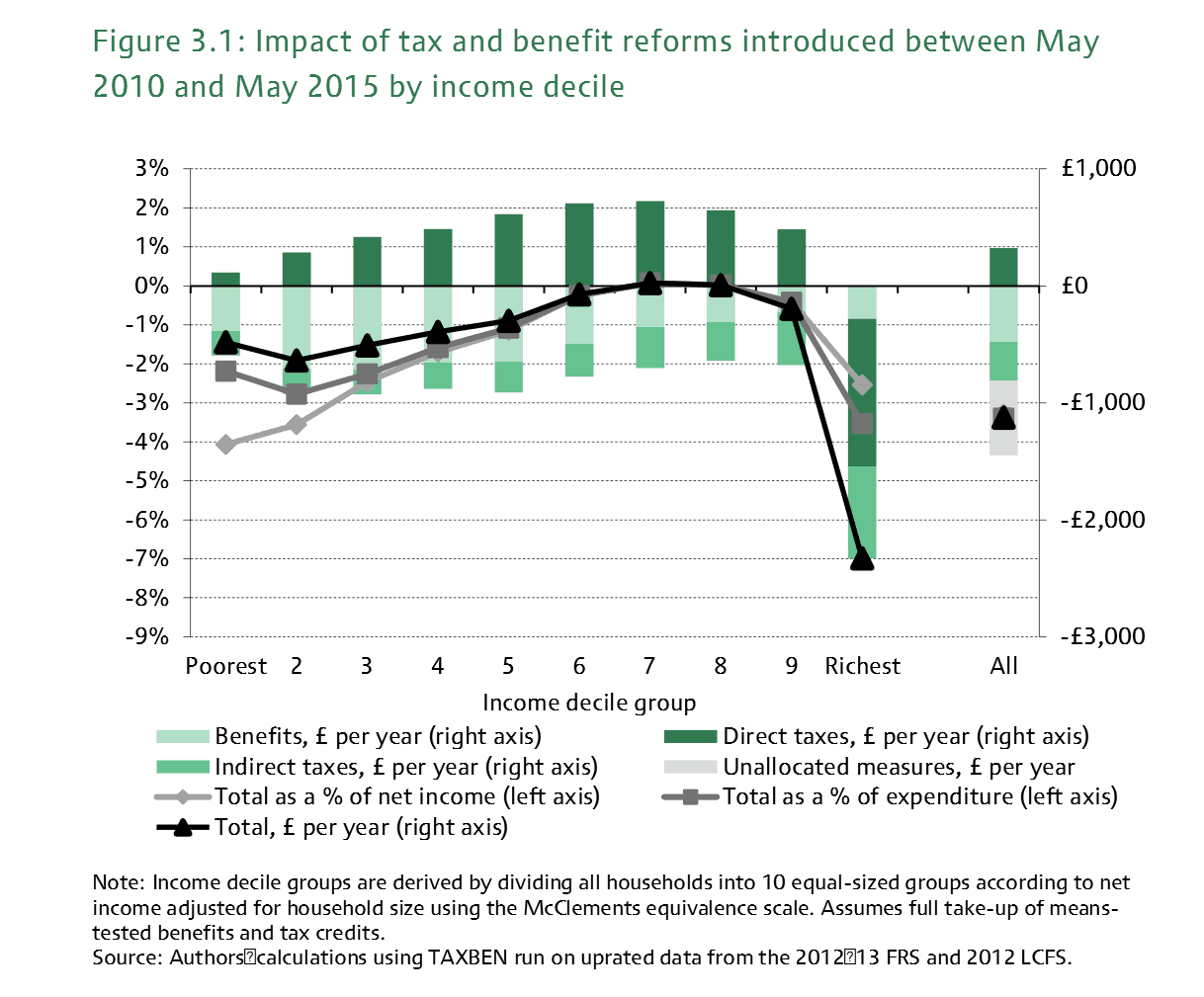

But more recently the highly respected Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) published a study of the effects of government policies on tax and benefits on people of different income bands. For the rare few voters who are interested in the facts of the coalition’s record this 30 page report is a fascinating read. The core of it is contained in this graphic:

What this shows is that the burden of the changes has fallen hardest on the top decile, but that every other decile has benefited from a reduced tax burden (i.e. the solid green bars), mainly the increase in income tax allowances. That, of course was the Lib Dem manifesto promise in a nutshell. Reductions in tax credits and benefits, however, have hit the poorer, so that as a proportion of income the overall effect on the bottom decile has been greater than the top (about 4% to 3%). The lucky 7th decile have suffered a net effect of nil. Further analysis shows that households with children have been hit the hardest, while even the poorest pensioner households have been protected:

What this shows is that the burden of the changes has fallen hardest on the top decile, but that every other decile has benefited from a reduced tax burden (i.e. the solid green bars), mainly the increase in income tax allowances. That, of course was the Lib Dem manifesto promise in a nutshell. Reductions in tax credits and benefits, however, have hit the poorer, so that as a proportion of income the overall effect on the bottom decile has been greater than the top (about 4% to 3%). The lucky 7th decile have suffered a net effect of nil. Further analysis shows that households with children have been hit the hardest, while even the poorest pensioner households have been protected:

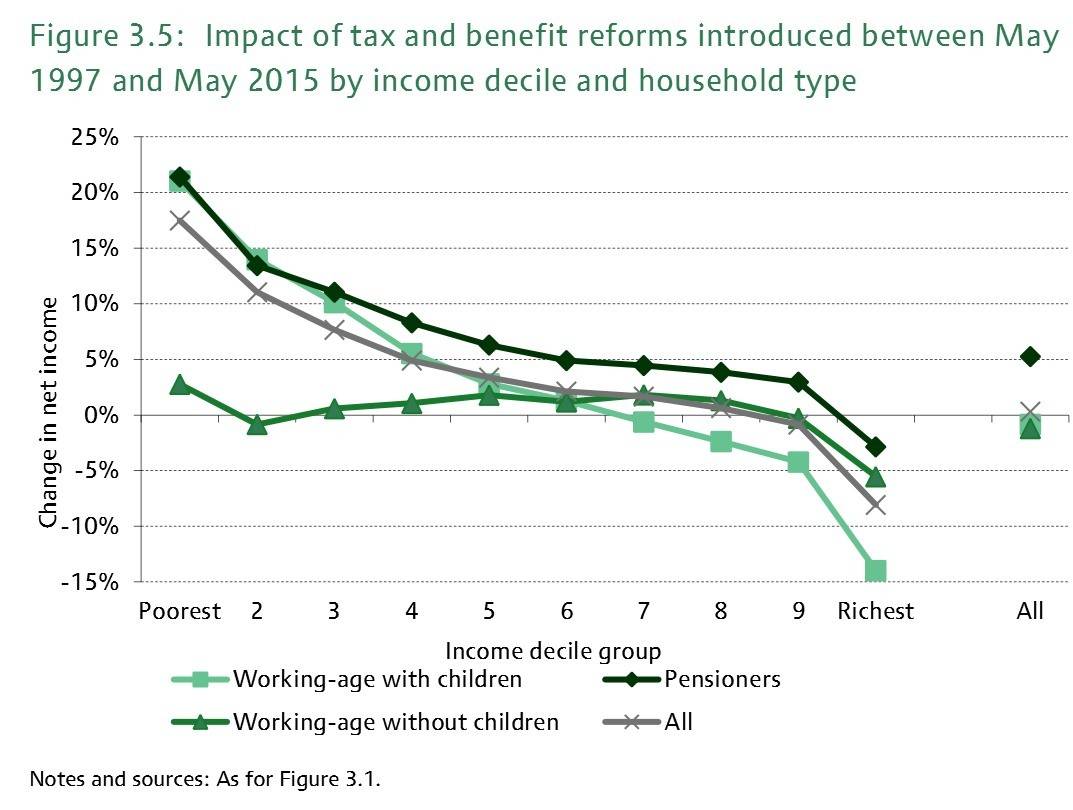

This represents a reversal of generous policies for families from the last government. If you take the whole sweep of policy since 1997 you get the following change:

Now this shows that the treatment of families overall lines up with that of pensioners – but that working age people without children have ended up with little net benefit. This may feel a bit harsh, but politicians have never suggested that their policies would do anything else. Pensioner and child poverty were the stated priorities.

And in case you are swept on by leftist rhetoric that these changes will be swamped by changes in income inequality before tax, a separate IFS study suggests that pre-tax income inequality has actually narrowed over the period of coalition. Put the two together and you get the picture of a government with a clear agenda to redress income imbalances. All this follows the policies Liberal Democrats advocated before the election.

The Treasury is also held responsible for managing the government’s overall finances, and Mr Alexander had a critical role in managing government expenditure. In 2010 the Conservatives promised to eliminate the structural government deficit in 5 years. Labour and the Liberal Democrats converged on about 8 years. Guess what? Though the coalition initially talked about the former target, it moderated when the economy struggled, and it is on course to follow the original Lib Dem (and Labour) target. Overall economic growth projections have disappointed the politicians, of course. But what, in Labour’s alternative strategy, could have led to a better overall outcome? They called for a softening of austerity and that’s exactly what the coalition did. Beyond some sound and fury over Keynesian stimulus, now irrelevant, Labour has had nothing to say about redressing weak productivity, the real reason for the lack of economic growth and real incomes. The scale of the deficit was such that it was always going to be hard going.

So Mr Alexander has, in spite of his position as junior to one of the most powerful men in the Conservative party, delivered a government record that is much more similar to what the Lib Dems had planned than the Tories had (they had planned to be much easier on the rich). Quite a record.

How does that compare with other Lib Dems? Poor old Mr Clegg’s political reforms have largely sunk without trace, and he also failed to spot the problematic NHS reforms quickly enough (as did Mr Cameron). Vince Cable was responsible for the reversal of Lib Dem policy on tuition fees, as well as the PR disaster of the Royal Mail flotation. Chris Huhne and Ed Davey battled valiantly at Energy but have had to give ground on nuclear power and fracking. Michael Moore and Alistair Carmichael at the Scottish Office have supervised a calamitous straining of the Union. All of these men, it should be added, have a string of positive achievements too, but they’ve been forced to compromise more than Mr Alexander has. There have been some impressive performers in the junior ranks (Steve Webb and Norman Lamb in particular), but their scope is inevitably narrow. Surely Mr Alexander is top of the heap?

So why are Lib Dem members reluctant to give him credit. First is a rather indifferent record on media interviews. He lacks a sense of ease and the ability to move away from pre-prepared sound-bites, unlike his Lib Dem cabinet colleagues. He doesn’t sound as if he is in command. He manages the detail rather than the big picture. And he sounds a bit Tory sometimes in the messages he gives.

But I don’t think that’s all. I don’t think that many Lib Dem members are at ease with the government’s record on tax and benefits. Those graphs in the IFS report show that the effects of increased tax allowances have not really helped the poorest, and that cuts to benefits and tax credits, especially to those with children, have squeezed the bottom half of the wealth distribution. There has been no offsetting increase in real incomes before tax. Labour have been energetically pointing all this out.

But given Lib Dem promises on tax allowances, on cutting the deficit, and on reforming pensions, cuts to benefits and tax credits were absolutely inevitable. The government has already gone after the richest 10% heavily, in increased taxes and, especially, a clampdown on tax avoidance (something with Mr Alexander has particularly championed). The only major budgets that haven’t been heavily squeezed are those for education and the NHS (foreign aid does not count as major), something Lib Dem members would support. Benefit cuts may not have been in flashing lights in the Lib Dems’ manifesto for 2010, but they might as well have been.

And this leads to a question that many Lib Dems would rather not think about. Just how much is it the state’s duty to top up low incomes with automatic entitlements to state benefits? And how much do such entitlements create dependency and a sense of victimhood from rich and poor alike? The great Liberal designer of the the welfare state, William Beveridge, was very worried about creating unconditional entitlements. Just what he would have made of the blank-cheque of the old Housing benefit we can only imagine. But modern leftist thinking takes such entitlements for granted, forever trying to raise the bar. But most of the public regards the idea of topping up incomes with taxpayers’ money with suspicion. It stinks of a freedom with other peoples’ money.

Personally, I think the expansion of automatic benefit entitlements is a blind alley. Instead we need much more intelligent and directed interventions to help people cope with poverty, and manage their way out of it, if they want to. This needs to be done in a person-centred way that to tackles the underlying problems (housing, mental health, addiction and so on) head on, instead of paying people money to go away and keep quiet.

But that’s just my view. Meanwhile Mr Alexander has implemented a liberal agenda at the Treasury and deserves more credit than he gets.