Last weekend my wife and I went to Oslo, to visit my brother and his partner (who is a local). It wasn’t my first visit to Norway, but the first time was on a tour. Norway comes up periodically in conversation here in the UK, especially as a country that does well outside the EU. What to make of it?

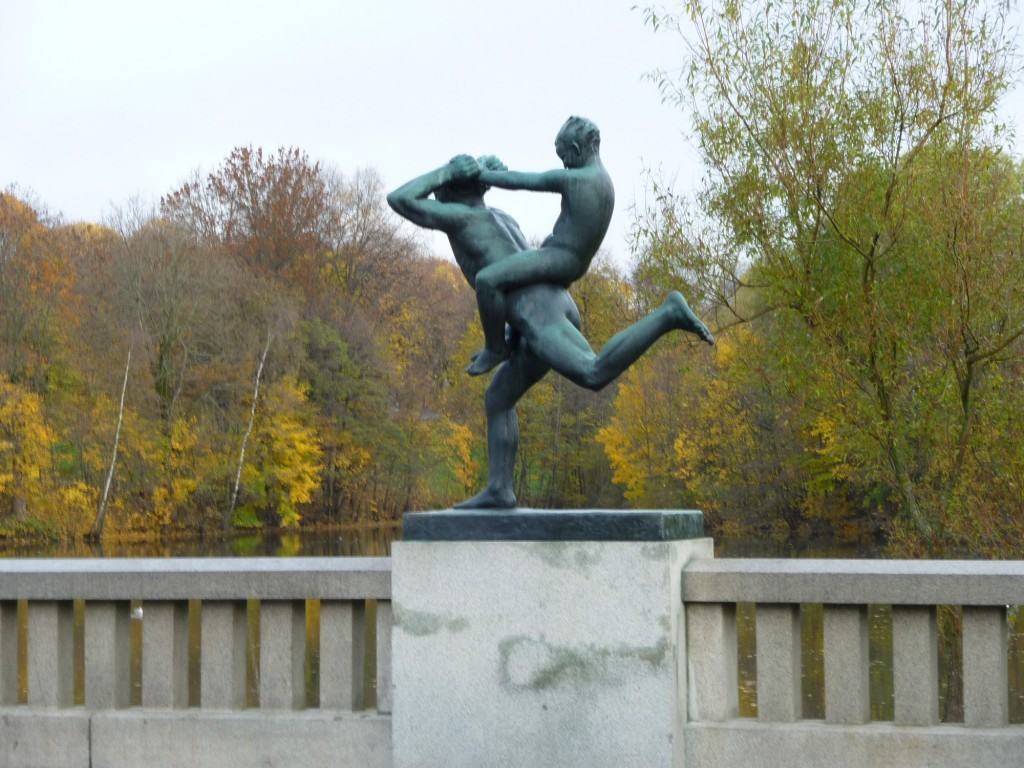

The first thing to say is that Norway is a spectacularly beautiful place. The weather was mostly dull when we were there, but we had sunshine on Saturday, rendering beautiful views of a totally calm Oslo Fjord. The architecture is mostly pleasing, if unspectacular – with some lovely 19th and early 20th century houses. We caught the short season of autumn colours perfectly. And of course the mountains and fjords are justly famous.

And the second is that, unsurprisingly, it has a very Scandinavian feel, from the language to the architecture and the people on the orderly and tidy streets. But there’s a difference, with Sweden and Denmark anyway. Norway has only recently emerged into what we would recognise as civilisation, that is a city based culture, with the exception of Bergen, perhaps. The medieval, renaissance and the baroque eras have left the country almost untouched, notwithstanding spectacular advance in the 19th century, in Oslo at least. Push back into history and you are into the land of trolls in no time. Of course what we call the Dark Ages was their Viking era, and that too was spectacular, though it has left relatively few traces.

The Norwegians appear to have had some struggle in coming to terms with this advance, with an excessive value placed on modernity. The most spectacular old monuments, undoubtedly world-class, were the ancient wooden stave churches. And yet many of these were torn down in the modern era as being old and useless reminders of a time they would rather forget. This has changed, with many wonderful wooden buildings preserved in the open air Folk Museum, including one of the stave churches. But family memories of the hard, poor rural life are widespread and fresh, especially compared to the long urbanised Britain.

All this has given Norway a clear national identity, albeit a more complex one that outsiders are generally aware of (is this not always so?). In modern times the country suffered further trauma under Nazi occupation in the War. And then came the oil. But the oil wealth found a well educated and cohesive society with strong, honest government. It has been socialised in a way that few, if any, other countries have managed, to make Norway one of the world’s wealthiest nations, while also remaining one its happiest.

Wealth comes with its problems. The exchange rate is high, and labour in short supply. Immigrants have been drawn in. Swedes are working everywhere in Oslo, and black and brown faces are common. High standards of political correctness (to give good manners their modern name) are maintained (plenty of brown faces in public ads and so on), but such changes naturally bring their own tensions.

So why does Norway stand apart from the European Union, unlike their Nordic neighbours? Well it’s not because they dislike regulations. Norway, I am told, is a much more regulated society than Britain. Perhaps that’s one reason that they have been given a generous deal under the EEA – i.e. full access to EU markets in exchange for partial compliance with EU regulations and some contributions to EU funds – which many British Eurosceptics somewhat unrealistically think would be available to the UK if it left the Union. While this deal exempts them from many aspects of EU regulation (notably competition laws), they still find that much of their law is based on EU directives over which they have no say.

No doubt Norwegians fear that, in the EU, the other members would eye up their wealth and seek to extract generous contributions. If they think that, they are almost certainly right. Norway is not ungenerous with its wealth, but no doubt prefers to contribute on its own terms.

The truth is surely that Norway is not in the EU because it does not need to be. Oil provides the country with all the exports it needs. It can negotiate other benefits. It carries no weight in the development of EU law, but how much weight would it carry if it was in? Norway is governed by a cosy elite that does not want to dilute its power. The population seems basically content with their elite. Not many lessons for the British there.