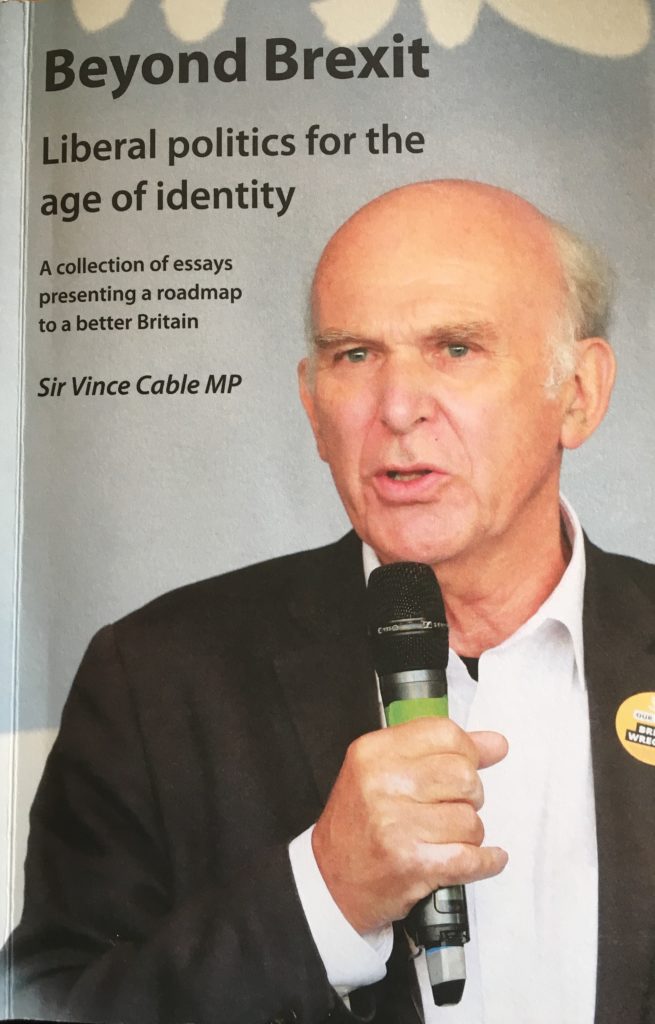

As we left the Liberal Democrats conference in York we were handed a small book: Beyond Brexit: Liberal politics for the age of identity, by the party leader Vince Cable. Vince had already announced his imminent departure as leader. This was his parting shot. Good and bad, it is a fitting verdict on his leadership.

Beyond Brexit is not a difficult read. It is a series of short essays, a few pages apiece, which flow well enough. Alas that is not entirely good news. Vince is a careful and studious politician. In his essays he likes to analyse what is going wrong. Along the way he also has another agenda: to defend the record of Liberal Democrats in the coalition government of 2010 to 2015. Both of these tasks are important. Too often the left dismisses current problems as being some combination of “austerity” and “capitalism”, assuming that this is obvious; the populist right similarly assume that problems arise from departing from the ways of the 1940s and 1950s. Likewise the Lib Dem record in government is dismissed as a big mistake on the basis that it was electorally disastrous for the party without bothering to understand what it actually achieved.

But the trouble is that this doesn’t leave much space to develop solutions. Too often these seem to amount to “maybe a bit of this, may be a bit of that”. The hope seems to be that we should trust somebody with wise insights about what is wrong to come up with good answers, without being very specific about what they are. No individual proposals seem particularly radical. No sweeping away of fiscal discipline; no universal basic income or job guarantee; no Green New Deal. Taken as a package, however, Vince’s ideas would be a radical alternative to the various paths proposed by the conservative right, the neoliberal right or the radical left. Whether it amounts to a radical departure from the social democratic left depends on how seriously we take his ideas on devolving power. Too often politicians drop such ideas when going gets rough, as it inevitably does; social democrats have no real patience for devolution.

Of course this lack of headline radicalism isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I tire of activists on the left who demand “radical” solutions. Such ideas have two flaws: almost by definition they go well beyond any evidence for what works (using the argument that everything else has failed…), and politically support for them tends to be narrow, so implementation requires some sort of mechanism to bypass consent. Most activists assume that the people are behind them, and that popular frustration with the system will lead to support for their form of radicalism – and it isn’t too hard to sneak such ideas through in a manifesto few people read. When they eventually collide with political reality, things are apt to get ugly. There is something to be said for a steady but gradual approach.

But political ideas don’t just need to be right, they need to hit the political zeitgeist. That is as much a matter of timing as it is of content. Mrs Thatcher seemed right in 1979; and her polar opposite, stylistically, John Major in 1990. Unfortunately now is not the hour for Vince’s understated intelligence and good-natured engagement. If his policy programme is right, it needs to be sold in a radically different way.

How? The most important step is to identify a single organising idea, with maybe a couple more to be held in support. This is plainly lacking in this book. It ends with a chapter on “My Roadmap to a Better Britain”, with ten points. All worthy, but these need to be organised around as few deeper themes as possible. Up until now the single organising idea for the Lib Dems has been opposition to Brexit. In the title of his book Vince rightly understands that the party has to move on from this: both because the issue will, eventually, recede one way or another, and also because it has become very tribal. Labour have such a theme: opposition to austerity. So do the Greens: radical action to reverse climate change. From Vince’s book there are a number of candidates for a Lib Dem theme, of which the main ones are education, environment (or the “Green Economy”) and political reform. There is also something he calls the “Entrepreneurial State” and housing.

Personally I think that political reform is the most important theme. The country’s politics is too centralised, while dominated by big parties that can be taken over by extremists. Fix this and the problem of disenfranchisement and the left-behind can be solved. But it suffers from two fatal drawbacks. First the British public is very conservative on political structures: we learnt this from the referendum on the Alternative Vote in 2011. They may agree that politics is broken, but they think that it is the politicians that need replacing, rather than the system that needs fixing. They are easily persuaded that any change will at best be a waste of time and money, and at worst make things worse. Brexit may be an exception, but that was sold on the basis of membership of the EU being a constitutional reform that had gone wrong or overreached – and being as unspecific as possible about what would replace it. And on that last point the country has become quite stuck, between conservatives who want to take the country back to 1970, and conservatives that want to leave things as they were in 2016. Secondly, when reform is about devolving power and improving democracy, it usually has the effect of giving sustenance to your political opponents. Proportional representation has helped conservative populists gain traction; local power centres are often conservative (as experience the highly devolved countries like Switzerland and Austria shows). To me this is a necessary part of the journey, but for most politicians it is simply self-harm.

The Green Economy, or Green Growth, has a lot going for it, as it combines popular concern for the environment with an answer to the challenge that it will make working people worse off. But both Labour and the Greens are likely to pick up something like a Green New Deal: a programme of top-down investments and regulations designed to have a rapid impact. While the Lib Dems may get away with camouflaging its more bottom-up approach with that name, it will be hard to make an impact in such contested space – which makes it a useful supporting theme, rather than the main line of attack (much as Labour will use it).

So maybe education is the best place to find an organising theme. There is no chapter on it in Vince’s book, but it comes up in several places. Fourth in his roadmap is “The best education in the world”. In particular Vince wants to develop vocational and lifelong education, especially through FE colleges. This is promising. Also the way in which the Conservatives have let loose the Treasury cynics on Britain’s schools is both damaging and unpopular. While some schools are not as financially well-run as they could be (though many are), this drive points to a narrowing of the curriculum and tossing difficult cases out of the system. This is desperately short-sighted. So education will resonate as an issue with a lot of voters.

But more important than that, liberals really believe in education. It is mass education, above all, that has spread liberal ideas. And a liberal education is probably the most compelling liberal idea, as it is a surer path to personal development than the rote-learning preferred by conservatives. The biggest weakness of populism is that it stands for a reversal of gender-fairness, and a rejection of diversity of race, culture and sexual orientation. This horrifies most younger people – which is clearly a function of improved education. In countries where education is weak younger people are as susceptible to populists as other age groups. There are pitfalls: too much open propaganda for liberal values in schools can, paradoxically, look intolerant (look at the problems sex and relationships education can have). Faith schools are a particularly ticklish issue. And neoliberals have too readily assumed that improving education is a substitute for other policies that address personal and regional inequalities. High quality universal education is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a fairer society.

But I suspect that Vince, ever the economist, thinks that his economic ideas should be the key theme: the first two ideas in his roadmap are “Strong public services and honest tax” and “An entrepreneurial state”. And yet I can’t see how that can be turned into a rousing organising theme to tackle the challenge of identity politics.

Such will be Vince’s legacy. I feel that he was the right man at the wrong time. I hope the party can find a replacement who is both capable of developing a strong policy programme and selling it to the public at large.