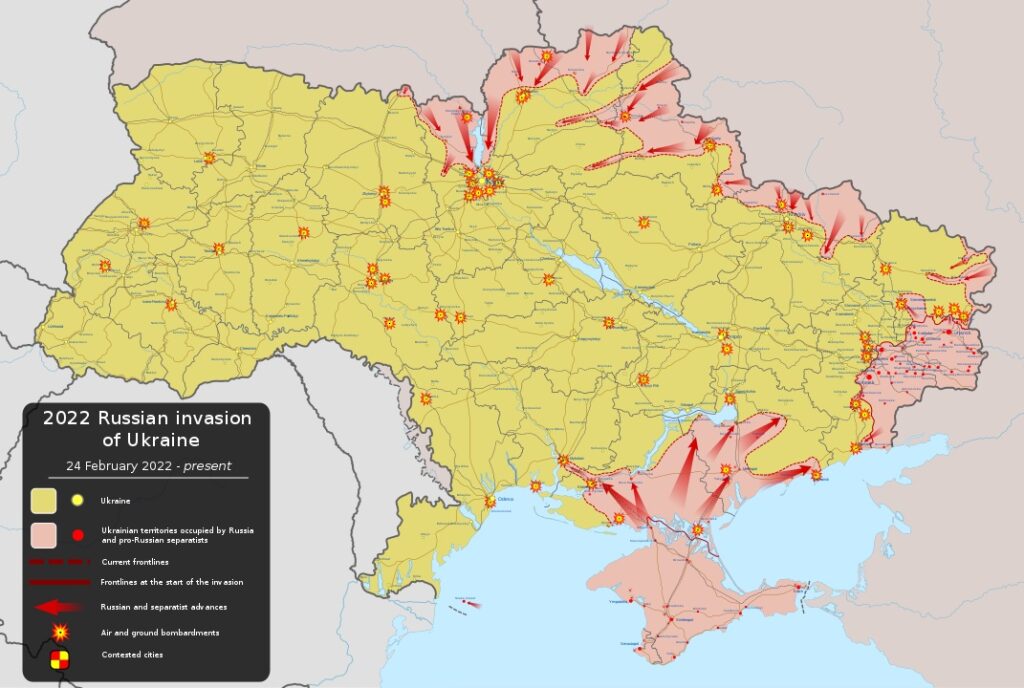

The month-long war in Ukraine is has entered a new phase. Neither side seems to be in a position to make major advances – but the fighting goes on with longer range weapons, causing continued death and destruction. The misery remains for Ukrainians and there seems to be no end in sight. It is a human catastrophe.

Most of the fighting is now around Mariupol. According to BBC correspondents, this is part of a new Russian strategy which focuses on one major objective at a time. Once this objective is secured, they will move on to the next: Odessa perhaps. This fits with a broader narrative followed by BBC correspondents that Russia has overwhelming resources and progress is simply a matter of time. Personally I am sceptical. It is quite hard for the Russians to replace the sort of resources they need to carry out an effective offensive campaign. After Mariupol, they may be too exhausted to do much more, apart from continued bombardment. A stalemate is likely to continue until something big breaks on one side or the other, militarily or politically. Both sides will seek to cover up their vulnerabilities and it is very hard to predict where the cracks will show first.

Meanwhile, I want to step back and look at the blame game. Two narratives are doing the rounds, suggesting that the war is the West’s fault. These are variations on the general, post-colonial narrative that everything that goes wrong is the responsibility of the Western powers, and especially America; everybody else is a victim. This is based on two ideas: one being that the West is all-powerful, in soft and hard power, and so has the ability to shape events everywhere. The other is a victim narrative, popular amongst developing nations, China and Russia, which seeks to absolve anybody else from blame for anything bad happening, often by digging back to some historical misdeed as an underlying cause. Neither is very convincing, especially in the Ukraine context, and, to be fair, few in the West are blaming anybody other that Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia for breaking the great taboo – using a military campaign to solve a political problem.

Still, seeking to blame yourself for things that go wrong is a better habit than always blaming somebody else. It is much easier to change your own behaviour than to convince anybody else to change theirs. It is worth asking what mistakes Western leaders made that might have spared us this tragedy. So what are the two blame narratives? One, popular on the left, and taken up by Chinese commentators, is that Western leaders disregarded Russia’s prestige and security interests, especially with the westward expansion of Nato and the EU. This forced Mr Putin into his death spiral of paranoia and a desire to rectify Russia’s humiliation. The other narrative is popular on the right: this is that Western leaders ignored the emerging threat from Russia, and were too busy engaging with the country rather than pushing back, allowing Mr Putin to think that he could get away with it. The West’s response to Russia’s attack on Georgia in 2008 and Crimea and the Donbas in 2014 are critical aspects of this narrative.

The first point to make is that these two narratives are incompatible. They can only be reconciled by suggesting that Western leaders followed a false middle path – aggressive enough to provoke, but too weak to head off the threat. That is an interesting thought, but we need to look at each of the component narratives a bit more closely first.

There is a case that Western leaders, and in particular George Bush Senior and Helmut Kohl were too aggressive in taking advantage of the collapse of communism. They took the opportunity to cut Russia down to size with a decisiveness and ruthlessness that was too much even for Britain’s Margaret Thatcher, usually referred to as the “Iron Lady” in her confrontational zeal. There is particular criticism of the lack of economic aid as the communist economy collapsed. Instead Russia was flooded by neoconservative economists who urged that nothing should interfere with the operation of market forces in the building of a new economy. Well-connected individuals, and organised crime, took advantage of the power vacuum to make fortunes, while life for most Russians was misery. What Russia really needed was a managed transition to a mixed economy – something the Chinese achieved in the 1980s and 1990s. But the main problem was weak leadership of Russia’s political class – something that was reflected too in other parts of the Soviet Union, not excluding Ukraine. Would Western aid have achieved anything lasting in the absence of such leadership? There is good reason to doubt this – though that is not to say that the Western powers should not have done more.

The next problem came with the breakup of the USSR. This followed the Soviet Union’s internal structure, which did not necessarily make political sense. At the core of each of the USSR’s component republics was an ethnic group distinct from Russia. But that did not necessarily add up to a sensible separate polity. Belarus in particular did not make sense as a separate nation, and Ukraine was dominated by Russian-speakers, even if they might not all call themselves Russians. Never mind: each of these republics became an independent country, while statelets within the Russian federation, such as Chechnya, did not. There was nothing rational about this, but it is hard to see what the West could have done about it, even if it wanted to. The problem was the collapse in authority by the central Soviet state. This then created a dynamic that was very hard to reverse. There was possibly something of a window in the early 2000s when Russia seemed a little less chaotic and better governed than most of the other republics, and might have reunified with Belarus and Ukraine. It is surely true that European and American leaders did not encourage this idea, in order to prevent the new Russian state becoming too powerful. But Russia chose to advance its cause by allying itself with autocrats who were spectacularly corrupt., stoking popular resistance in Ukraine in particular.

But the biggest grievance of Russia’s leadership is the expansion of Nato and the EU that took place at this time. This included most of the old Warsaw Pact countries in Central and Eastern Europe, together with the three former Soviet Republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Let us take the EU first. Russian leaders tend to see this as an aggressive expansion of a zone of political and economic interest by West Europe. In a sense they were right – but it was motivated by the wish to consolidate democratic values and strengthen the European economy. It has broadly succeeded in both aims, notwithstanding many problems, notably in Hungary, Rumania and Bulgaria with political corruption, and populism in Poland. Funnily enough there have been fewer such problems of integration among the former Soviet republics that joined. All these countries have prospered relative to the former Soviet republics that did not join the EU, for reasons that will be the subject of many an academic study for generations to come. It his hard not to see this expansion of the EU as a brave political move to benefit the peoples of Europe, rather than a provocation to keep Russia in its place.

That case is less easy to make for the expansion of Nato, which Russia challenged at the time. Personally I felt at the time that the admission of former Soviet republics to Nato was a step too far. But the new entrants clearly wanted to be part of the alliance, and it is hard not to argue that the threat from Russia was a real one. The West tried to reassure Russia with an agreement to limit the deployment of forces in the new countries – an agreement that they have broadly honoured until the Ukraine war. It is very hard to portray this expansion of Nato as a military threat to Russia, which doesn’t stop some people from trying. In the far left narrative Nato’s aggressive intent has been shown in its campaigns in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq and Afghanistan. But you really have to have the sort of world view that sees Cuba as a brave democracy in order to give this sort of thinking serious weight. But what Nato and EU expansion clearly presented was a limit to Russia’s ability to expand its own influence, and in particular opportunities for the self-enrichment of Russian elites. And yet it is very hard to subscribe to the principle of democratic consent and accept that Russia has a right to treat these countries as part of a sphere of influence, reminiscent of great power politics pre-1914.

The next step in the provocation narrative is the West’s growing influence in Ukraine. There was, in fact, no real prospect of this country joining either the EU or Nato. Oligarchs had too much influence over the state structures for the former, and ongoing territorial disputes with Russia doomed the latter. But western countries would not rule this out formally. Furthermore they have been very supportive of reforms that would push back the corruption rife in Ukrainian public life, which Russia has seen as an important channel of influence. Ukrainians in general have shown a clear preference for closer ties with the West, especially after Russia seized Crimea in 2014 and supported separatists in Donbas, kicking off a nasty war in which many Ukrainians were killed. Before this it was possible to sustain a narrative that Ukrainian politics was a battle between Ukrainian-speaking nationalists in the west, and Russians in the east, with the former only achieving political power through corruption, and using it harass Russian-speakers. The war in the Donbas changed that – though that surely some Ukrainians would still like their country to be part of Russia. But even before the current war, most Russian-speaking Ukrainians looked to the West, and the way they voted in elections clearly demonstrated that.

And that, at heart, is the problem with this Russia-the-victim narrative. The current Russian regime is a bully that believes in subverting the interests of its neighbours to support those of their ruling elite. Do we simply accept this as a matter of realpolitik, or do we push back? And where do we draw the line? Personally I would have drawn a pretty hard line around the borders of the former Soviet Union, and allowed Russia a greater level of influence there, even if it was malign – including an effective veto over Nato membership. But what would the outcome of that have been for the people of Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia? The examples of Belarus and Moldova are hardly encouraging. What I find very hard to take is people on the left supporting this Russia-the-victim narrative, using classic arguments of realpolitik. They would have been much better sticking to the high moral ground and comparing the behaviour of Russia to that of Israel, for example. To their credit this is what some of them have done.

Which brings me to woolly-West narrative. This line of reasoning instantly raises hackles with me because it reminds me of Cold War arguments in the 1970s – which I fully subscribed to at first, before moving on. Actually it may have more justification this time. The argument goes that Mr Putin was committed to his confrontational course in the early 2000s, if not before, and nothing was going to shake him from that path. Better to have frozen Russia out earlier, especially after his attack on Georgia in 2008. This may have weakened Russia economically and even militarily. But that would have given Russia little to lose from aggressive military campaigns against its neighbours, with a distinct risk of a nuclear confrontation. The West wanted to present Mr Putin with an alternative path of continued economic integration with the West, leading to greater domestic prosperity. Even so, the passive behaviour of Germany in supporting Russian gas exports while neglecting its military was not a good look.

There is a little bit of truth in both the West-is-to-blame narratives. But the West’s middle path of wary support for emerging democracies in Eastern Europe, combined with not treating Russia as an enemy was a perfectly rational one. It is hard not to see Russia’s troubles as being primarily driven by mistakes and weak leadership within Russia’s ruling elite in the 1980s and 1990s. After this a democratic path was open to its leadership but tackling corruption and building an open economy; or alternatively there was the Chinese model of developing a competitive private economy while tackling corruption in the ruling elite. But Mr Putin chose not to follow either path. Military assertiveness is not the only way to respond to political humiliation, as Germany and Japan have proved. western leaders may well have made mistakes in their management of Russia – but would that have stopped a war like this being started by Russia? That is much harder to say.