The Ukrainian war is an important test of British journalism. I have mainly been following events through the BBC, supplemented by the Financial Times and The Economist – with snatches from elsewhere. This coverage is wildly better than anything coming out of state-controlled media in Russia, for example. But some, especially on the left, feel it is biased. I only get snatches of the frustration from Facebook, as I observe comments on the feed of a contact whom I respect in spite of her engagement with the wilder left. Many of these commenters snatch at anything that throws doubt on the narrative coming out on mainstream media. But the main thing to know about this critique is that it has negligible political impact, and isn’t worth getting worked up about it.

Still, the mainstream coverage is far from perfect. As ever, it is drawn to spectacular pictures and individual stories and loses a lot on perspective. It is hard to know how much damage to civilian areas is “collateral”, in the manner of US and British action in Iraq and Syria, and how much is deliberate targeting of civilians (as has been the case in the Russian-backed campaign in Syria). After days of talking about a devastating bombardment of Kharkiv, for example, I was surprised to see pictures of civilians taking trains and cars out of the city in areas that were clearly undamaged. Kharkiv is a big place, of course, but the BBC seems to be using the same old photos to illustrate its stories of the damage there.

Another niggle is that BBC correspondents have a tendency to talk up the strength and power of the Russian forces. They talk of overwhelming strength, and simply as assume that Russia can deploy this strength to prevail in the long term. Others suggest that Russia can rerun its campaign in Chechnya, or the Russian-led one in Aleppo.

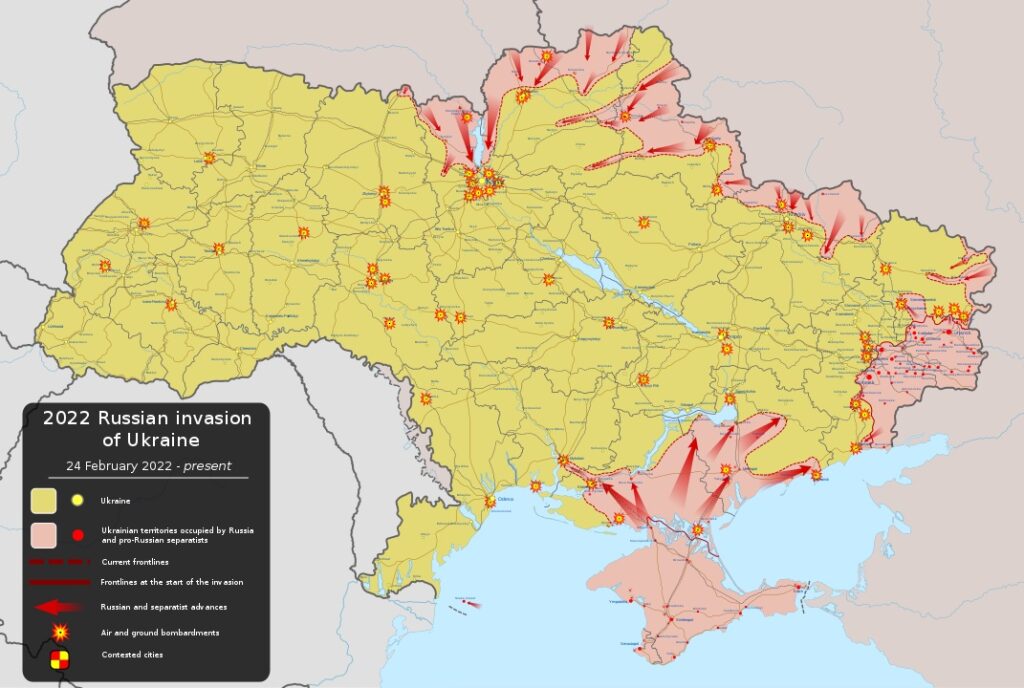

But the situation in Ukraine is very different to Syria or Chechnya. It is a much bigger theatre, and the forces opposed to the Russians are much larger. Russia doesn’t have enough troops. Western experts believe that 95% of the forces brought forward by Russia for this campaign have now been committed. And this was about 75% of Russia’s army. Including reserve forces, Ukraine’s army is more than twice its size, not counting the numbers of civilians (and foreigners) enrolling. But, of course, the Russians are regulars, and better organised, and much better equipped. As the attacker they can choose the battlefield and apply overwhelming strength there. Except, for some reason, they haven’t. Russia has spread its forces across many lines of advance. Russia’s main advantage is in vast quantities of ammunition for longer-range weapons: artillery shells, missiles and bombs. While they must be running down stocks of these, they do manufacture their own, and it is much easier to ramp up production of these than it is to recruit men.

And that is leading into a stalemate. Russian forces are making slow progress: to the east and west of Kyiv, and expanding their bridgehead from Crimea. But it is far from clear whether they have the wherewithal to launch substantive attacks on Kyiv, Odesa or Zaporhizia, which appear to be the targets – though they may be able to overwhelm Mariupol, where things are clearly desperate. Of course I don’t know how much the Russians and Ukrainians are holding back. The Ukrainians might be stretched to breaking point, and vulnerable to a well-placed offensive from Russian forces. Or they might have reserves that they can put into a game-changing counter-offensive, once Russia has committed to its next major push forward. But my guess is that a horrid stalemate is approaching. In many ways that is the worst possible outcome for both Russians and Ukrainians.

What can the Russian regime do? It is apparently trying to scrape together some extra forces, including the recruitment of foreign mercenaries. It could start calling up conscripts and reservists. Vladimir Putin has apparently ruled that out today – but what worth are his promises? He can simply ratchet up the narrative about the existential threat to Russia from the West. But such a measure would have a huge political cost, given that he has done little to prepare the Russian public for a major war against fellow Slavs. Alongside Western sanctions taking effect, taking away that easy access to the West and western consumerism which seems to be so important to Russia’s middle and upper classes.

The war is increasingly looking unwinnable from both sides. Russia is a first-rank power militarily, but not economically. It will find it hard to sustain an all-out economic war with the West, even with the qualified support of China (who will want to limit the damage to their own economic relations with the West) without huge damage. It lacks the manpower required to win the sort of people’s war that the conflict is becoming. Russia has a strong national identity to call on, but the threat to its people from Ukraine is abstract, while that to Ukrainians from Russia is all too real. Ukraine, meanwhile is in the process of forging its own national identity. One thing we don’t know is how much support there is for joining up with Russia within Ukraine. There is doubtless some, but the mainstream media is not reporting it at all – as doubtless people with that view are keeping their heads down. But what is clear is that most Russian-speaking Ukrainians now identify as Ukrainian and not Russian. With continued support from the West it looks as if they can sustain the war for a long while yet. They can dig deeper into their own human resources than Russia can.

Which leads to the question of what will Russia’s break-point be? Vladimir Putin has backed himself into a corner. He may have downplayed the level of military commitment to the Russian people, but he has given them maximal objectives – to ‘de-nazify” and demilitarise Ukraine – not simply to ‘liberate’ the Donbas region and secure recognition for Crimea. It looks impossible for him to declare victory and get out. And that surely means that the only way to stop the war is to remove him from power. That would require some form of putsch. For that, the situation in Russia would have to become intolerable. How far away is that? That is another thing I cannot know. But as somebody who is steeped in Russia’s intelligence services, Mr Putin has surely payed a lot of attention to his personal security.

All of which leaves us with a grim outlook of months more killing and suffering. We thought that Europe had learned enough of the futility of war. It is heartbreaking to see that we are having to learn this all over again.