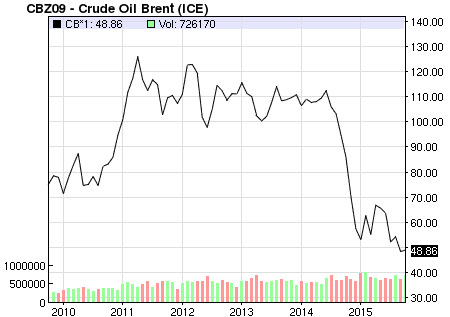

For much of 2010 a barrel of Brent crude oil sold for under $80.

Then it started to take off, so that in early 2011, it reached $125. Around this time, perhaps not coincidentally, the Scottish National Party (SNP) achieved a stunning victory in the Scottish parliamentary election, allowing them to govern on their own, in spite of the proportional voting system. In the following three years the oil price held at around $110, and it seemed quite reasonable for the SNP to assume that prices would stay there for its financial projections for Scottish independence for the referendum in September 2014. But by the time that referendum was held the price was in free fall. And, again perhaps not entirely coincidentally, the SNP lost the referendum. Now Brent crude trades at under $50. It may be stuck there for some time. Hold that thought in your mind; it is the most important thing to understand about Scottish politics. Scottish nationalism has always been closely linked to oil.

After reviewing the fortunes of each of Britain’s major parties after their Autumn conferences (and one minor one: my own Liberal Democrats) it is the turn of the SNP. Notwithstanding the loss of the referendum, the SNP’s dominance north of the border looks complete. The only way from here seems to be down, but when, on earth, is that going to be?

Commentators on Scottish politics from London, of which I’m one, are notoriously bad at understanding Scottish politics. As, indeed, are English politicians. But surely the same laws of physics apply on both sides of the border? We must try to understand what is happening, and where things might go.

First we need to understand how the SNP achieved its dominance. Nothing could be sillier that the narrative I have heard put about by English leftists that the SNP achieved its success through tapping a popular, anti-establishment mood, and in particular anger at “austerity” to become “a broadly based social democratic party” as one article put it. This is silly not because it is entirely untrue, but because it is so incomplete that it might as well be. The SNP has achieved its success because it has convinced Scottish voters that it is the best party to look after their interests. This is not based on any particular policy stance, but through an appeal to national identity.

First they destroyed the Conservatives, who used to be a major force in Scottish politics. They were aided in this by the complete ineptitude of successive British Prime Ministers, Margaret Thatcher and John Major. They managed to make the English look like an occupying power. The SNP were nicknamed the “Tartan Tories” by Labour, because of their appeal to right of centre voters. Their leader of the time, Alex Salmond, sounded distinctly neoliberal, with his wish to turn the country into a corporate tax haven, like Ireland.

But Labour fared better. In New Labour days, that party’s domination of Scots politics started well. The party delivered devolution and won the first two Scottish parliamentary elections, governing in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, who also performed respectably. It no doubt helped that one of New Labour’s architects, and its second Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, was very much a Scottish MP. But doubts were raised about the party’s commitment to Scotland. Its best politicians seemed much more interested in pursuing a career in Westminster than in Holyrood. The party struggled to find a convincing leader after Donald Dewar, Scotland’s first devolved First Minister, died in 2000. Labour’s Westminster “strategists” (as politicos like to call their tacticians) took Scotland for granted. The party’s seats in Scotland were mostly quite safe; there was little understanding of how to handle political competition.

The first cracks showed when Labour lost the Scottish elections in 2007 (by a single seat), allowing the SNP to form a minority government. But the party would not, or could not, understand the implications of giving the SNP such a lift in credibility. After all, Labour did well enough in the 2010 British general election in Scotland. But they should have understood the strategic implications when the party fared badly in Scottish elections of 2011, allowing the SNP to achieve that majority, and a mandate to hold an independence referendum. Labour continued to flounder. To be fair, the party was facing such deep strategic problems after losing power in Westminster in 2010 that it was difficult for them to do other than paper over the cracks and hope for the best. The party’s lack of political skill in Scotland, however, became evident to all in its incompetent leadership of the referendum campaign. The party really seemed to be only about providing careers for talented politicians in Westminster, local jobs for the others, and no use to Scots voters at all.

The SNP, of course, managed to use the referendum to generate a surge of interest in an optimistic brand of politics based on Scottish identity. Its leaders then made a brilliant switch. Mr Salmond stepped down as leader, and handed over to his deputy, Nicola Sturgeon, who had the reputation of being more left-wing. Ms Sturgeon duly turned the focus onto Labour voters. She used the mantra “austerity” in her messaging, to demoralise Labour activists, fed up by their leadership’s more careful line on economic policy. Labour collapsed to just one seat in Scotland (the same as the Lib Dems and the Conservatives) in May’s British general election.

The Labour left hoped that Jeremy Corbyn’s ascent to the Labour leadership, amid a tide of new members, and his supposedly refreshing brand of “straight-talking, honest politics”, would change the party’s fortunes. Alas no. Scots voters deserted Labour because the party was useless to them. The party has merely turned itself from one form of uselessness to another. A chaotic debating society more interested in policy than power is not an improvement. The next Holyrood election is in 2016. Everyone expects the SNP to increase their majority, mainly at Labour’s expense (the Lib Dems were already crushed in 2011; the Tories have quite a robust core vote).

A further departure from the London lefties’ idealisation of the SNP is that the SNP conference was as far cry from the “new politics” they espouse. The Observer columnist Andrew Rawnsley said that it reminded him more than anything of a Conservative conference under Mrs Thatcher. The SNP are ruthless politicians, managing their message with discipline, and extending their hegemony to as many parts of Scottish life as they can. There is no open debate of party policy. This is not good for the quality of government there, but the party can and do blame any problems on the Westminster government. The SNP’s record is not all bad, though: the Scottish economy is more buoyant than any other part of the UK outside London and the English South East. Whether that arises from the SNP’s neoliberal tendency, or from its social democratic one, probably depends on who you talk to.

The SNP’s successful discipline arises from a clear, unifying purpose: their quest for Scottish independence. And therein lies their biggest strategic problem. That $50 oil price. That leaves little left to tax. It causes collateral damage to the oil industry based in Scotland. It makes much of remaining oil beneath the North Sea unviable. This knocks a huge hole in the SNP’s economic plans for independence, which handed out goodies to all interested parties.

The low oil price is a product of America’s shale revolution, and increased energy efficiency. Meanwhile Iran will re-enter that oil market, and demand from China is tailing off. That $50 price could be around for quite a while. The “peak oil” theory is dead and buried. There is no sign that the SNP have any idea how to plug the gap in their plans for independence between $50 and $110.

And here’s the thing. In spite of this price collapse in oil, the Scottish economy is performing well. It is diversified, and the non-oil bits are doing taking up the slack. The tax revenue damage is being taken by the UK as a whole, which unlike Scotland would be on its own, is big enough to absorb it. You could not have a better illustration of why the Union makes such good sense for Scotland. It acts as a wonderful economic shock absorber. And, as Greece and others have shown, joining a currency union does not solve this problem. Before long, Norway will be providing a clear illustration of the challenge an independent Scotland would be facing. Independence means austerity.

Ms Sturgeon used the conference to manage down her party’s expectations of a second referendum soon. But with a low oil price and deteriorating demographics 2014 may have been their best shot. Unless Britain is mad enough to vote to leave the EU, the case for independence will be more difficult to make in future. It will take some time before the penny drops. But surely the SNP’s days of hegemony are numbered?

But for their different reasons, Scotland’s other parties are unable to exploit the SNP’s strategic weakness. Paradoxically, though they may have won the argument on independence, it may not help to make too much of their unionist views. Just as England’s middle ground voters are not averse to austerity, Scotland’s middle ground clearly prizes its national identity, and isn’t scared of independence talk. Perhaps the tactic should be to concede the idea of a future referendum, especially in the absence of a proper federal settlement. That might clear the field to examine the SNP’s actual record. But that might take a higher calibre of leadership amongst Scotland’s opposition parties. For now the SNP does not face a serious challenge.