They look like a colossal waste of effort. Elections to the European Parliament take place every five years, and turnout in Britain, as in much of the rest of Europe, is dismal. Few understand what the European Parliament is for. But last night’s debate between Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg and Ukip’s Nigel Farage shows that things are going in an interesting direction. These elections are contributing more and more to the wider process of politics in this country.

The most important thing about theses elections is that they are held using proportional representation (PR). Parties in practice need to get over 10% of the vote in a particular region to get represented – but that still gives parties with a broad but thinly spread appeal a much better chance than parliamentary and even local council elections. The vote share won by the two parties that dominate conventional elections, the Conservatives and Labour, is dismal. This is adding a new dimension to the political debate because it offers voters a greater choice.

The conventional way of politics in the UK is to tell the voters that the real choice is between just two parties. Which two varies depending on where the election is being held, but mostly it is between Labour and the Conservatives (though Scotland is a big outlier here). This serves to close down political debate to a few carefully chosen swing issues that appeal to marginal voters in marginal constituencies. Minority views are dismissed as being irrelevant. But this line of campaigning does not work with PR. And the European elections are the only ones held under PR for most English electors (Scottish, Welsh, Northern Ireland and London Parliament/Assembly elections are held under PR).

The most obvious beneficiaries of this have been to the Lib Dems, the Greens, and, above all, Ukip. Ukip is a right wing insurgent party that represent political views that are as far away from mine as you can get while still being a respectable political party (unlike the openly racist BNP, for example). But it speaks for an important minority of mainly English voters who feel oppressed by the current political system, and ignored by the main parties. The EU is an important focus of that discontent, as is what is seen as excessive immigration. As an aside it often draws its strongest support from areas that are relatively unaffected by immigration – but that does not stop it being a popular scapegoat. The issues are linked: free movement of people is a vital plank of the EU project.

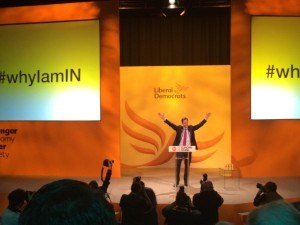

The Conservative and Labour parties would rather these issues were suppressed. They represent inconvenient divisions within their own ranks and put their internal cohesion under stress. And that led to last night’s debate. Ukip and the Lib Dems take clear sides, and are quite happy to slug it out in public. And the public gets to hear a proper debate. That is a very important part of the democratic process. Floating voters may not have learnt much from the verbal slugging match, which I judged to be a score draw (with plenty to please both sides), but it at least would have drawn them into the issues.

Where is this heading? In the great scheme of things I don’t think the direct European Parliament elections are a great success in closing Europe’s democratic deficit. I think its original configuration as a forum for delegations from national parliaments was a better one. But for as long as it is the only national election held under PR, it is serving a useful purpose. The right answer is to use PR for national parliamentary elections, but alas that aim remains very distant. PR for local elections may be a more realistic intermediate step.

Meanwhile it will be very interesting to see if the interest stirred by these debates will affect turnout at the elections. But even if they do not (I will only believe it when I see it) they are doing something to close Britain’s democratic deficit.