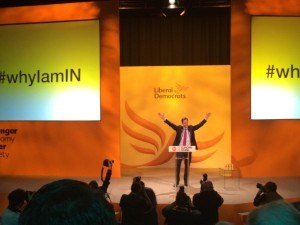

The Liberal Democrat conference ended yesterday on its fifth day with the party leader, Nick Clegg, giving his speech. By then I was on the train home, wishing to save money on fares as well as arrive home at a decent hour – though I have read a text version of the speech, and seen the comments. It ended an uplifting conference for the party. While good for the spirits, has it answered doubts over the party and its leader? It is a step forward.

The doubts centre around the party clearly articulating what it stands for. To date it has been keen to identify itself as covering the “centre ground”, and to spend time justifying its role in the coalition government. The problem with defining yourself as being centrist is that that you are using other parties to define yourself. The party risks presenting itself as either or both of “Labour-Lite” or “Tory-Lite”. This is not a convincing rallying cry. Neither is a list of policy proposals; if they are popular, the other parties will steal them. The Conservatives are already “stealing” the raising of tax allowances, the Lib Dem signature policy of this parliament. Lib Dem whinging about this, and the Tories getting the credit for the economic recovery rather than them, is all rather pathetic and will win the party no credit with voters. The public does not give the party credit because they don’t know what it stands for – beyond winning the prestige that goes with being in government. The policies and the record of action are the supporting evidence for a proposition, not the proposition itself.

Lib Dem activists have a strong idea of what the party stands for: liberalism. This is not the economic liberalism of the 19th Century, but one where the state plays an active role in making sure everybody gets the opportunity to develop and fulfil their lives. That “everybody” is a central idea – it is not qualified by national, ethnic, class or other identity. This leads to clarity around a certain set of policies: human rights, written constitutions, distributed political power, strong social insurance and a degree of redistribution of wealth and income, to improve the chances of the less lucky. There is also a strong environmentalist steak.

Amongst the general public, who do the Lib Dems need to convince? There are two main groups. First are those who are liberals, but who are more convinced by other parties – mainly Labour and the Greens, as the Conservatives seem to have given up on liberals. The second group are people who are drawn to non-liberal politics, being those of identity, individualistic self-interest, or a large centralised state, but might be convinced otherwise, perhaps as a second-best. A socialist may be convinced that liberalism is better than conservatism, if Labour are locally weak.

How did Mr Clegg and his party do? Better than before. Mr Clegg’s speech contained more about liberal values and why they make sense. He called for a “smart, liberal and enabling state”. The party made a clear stand against illiberal policies of their Conservative coalition partners. The signature policy Mr Clegg chose was parity for mental health with physical health in the NHS. If this is a bit tangential to liberalism (you don’t have to be liberal to support it), it will at least serve to draw attention. It showed the party capable of fresh thinking.

But it is only a start. I would like to hear more about the “smart, liberal and enabling state” – and in particular how it contrasts with Labour’s vision of the state. Indeed I think the party is being too soft on Labour, and needs to find some “wedge” issues that will pull liberals away from it. There is a bit of paradox in political presentation; you need to get over a strong positive message, but contrast is needed for visibility, which means that attacking other parties can be one of the most effective ways of defining your own. You need to say what you are not, and how you are different. The party is doing this with respect to the Tories, and the Tories themselves are lending a helping hand. But to a Labour sympathiser it opens the question of why the party is in coalition with the Tories, and thereby letting in a host of nasty Tory policies. It isn’t enough just say that the party stopped the worst ones, and put through one or two ideas of its own. The main reason the party ganged up with the Conservatives was the hopeless state of Labour – something that went further than their electoral failure.

Labour is a loose coalition of values and interests, albeit with a strong tribal solidarity. Liberals are an important part of this coalition, alongside public sector workers, state dependents, working class conservatives, left wing intellectuals and northern city council mafias. Lib Dems need to show that this Labour coalition is unable to produce coherent policies for government, still less implement serious liberal reforms. This means developing the vision of a “smart, liberal and agile” state, and showing how this is different from the Labour and Tory versions. At this conference the policy paper on public services presented some interesting new thinking on just that. That is only one piece of a jigsaw.

The Green Party is also worth a bit of attention in my view. It has moved on from a focus on environmental policies. In its current statement on values the first two of its three policy bullets are its opposition to austerity and to privatisation for public services – and only then does it cover climate change. This is no more coherent than Ukip’s policy stance. In Scotland the Greens supported independence in spite of the fact that the Yes campaign’s economic strategy depended on getting carbon out from under the sea and into the atmosphere as fast as physically possible. The party’s leader in England leader, Natalie Bennett, has also said that the party wants to avoid the responsibilities of government, and to limit any cooperation with a future government to case by case parliamentary support. All this is half-baked and could break up quite fast under scrutiny. Still I’m sure the professionals would urge that ignoring them is the best way of handling them. But they picked up a lot of liberal votes in my neighbourhood in the European elections this May.

But one thing is going for the Liberal Democrats. The main parties are concentrating on a core-vote strategy, leaving space on the centre ground. If the party can spell out its liberal vision more clearly, it can surely advance from the 7% support that it currently languishes at. It is gradually winning more respect, to judge by newspaper editorials. Its conference in Glasgow was a step forward.