The political parties are playing a blame game on the British economy. Yesterday another report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) was the unedifying battleground. This debate is interesting but unresolvable. And what matters is what the parties might do now if they were in charge. And on that neither Labour nor the Conservatives are convincing.

The controversy starts with the financial crash which began in 2007, and let to wider economic collapse in 2008 and 2009. The crash was a huge surprise to most politicians, and their electors. Before this steady growth of about 2% a year seemed to be a force of nature. There were squabbles about how best the proceeds of growth should be used. The downturn was very sharp, statistically the worst recession since 1945; comparisons with the 1930s are made. But in human terms things were not so bad as , for example, the early 1980s; we are a wealthier country with more fat to draw on – and unemployment did not rise as fast as earlier downturns.

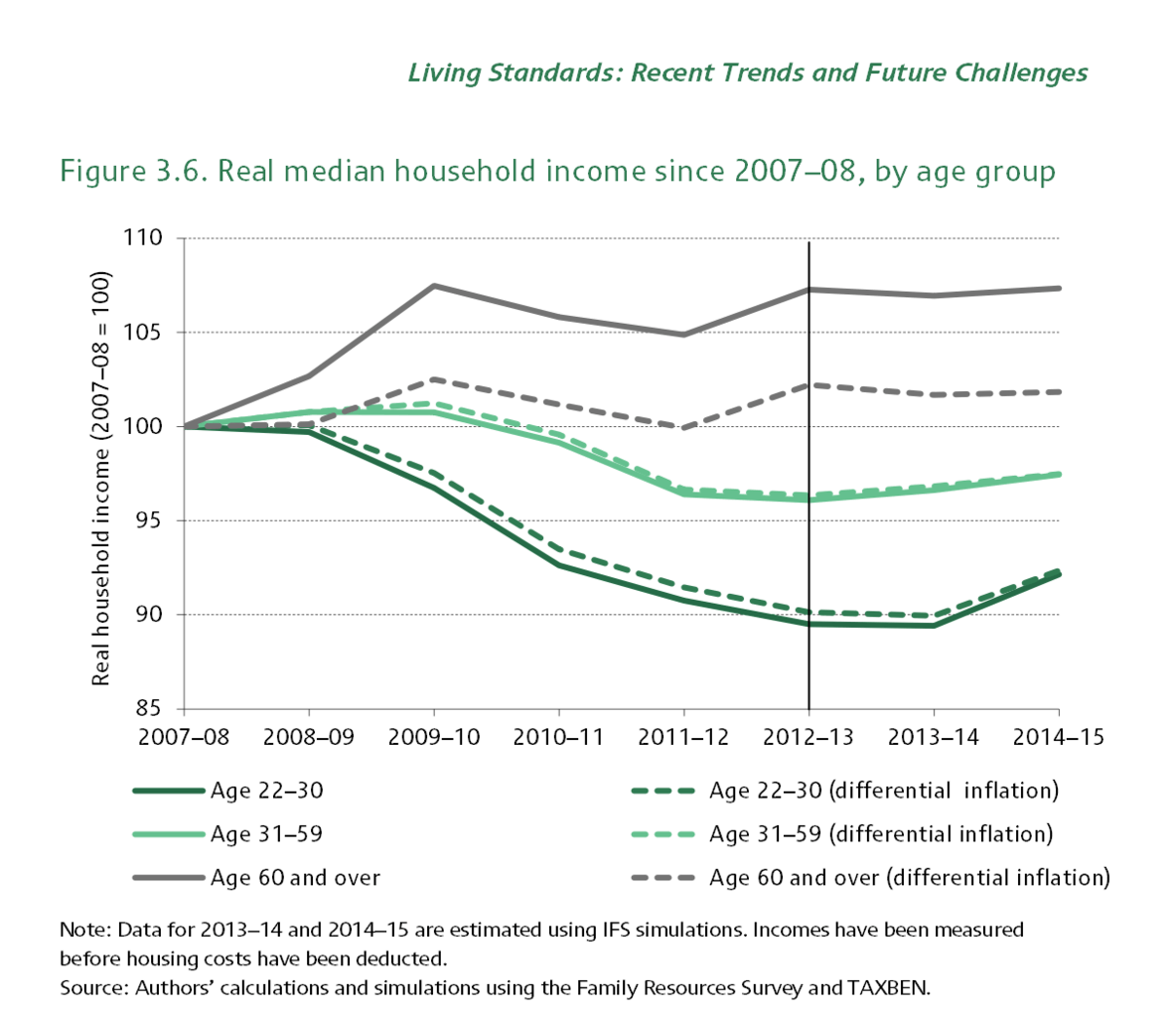

But two things stand out. Firstly, thanks to steady inflation and frozen levels of pay, real incomes have been squeezed since the crash. Previously those in work tended to do better, but there would be more unemployed. Secondly the recovery was very slow – and not the rapid bounce back typical of previous recessions. There is a very powerful graphic in the IFS report which shows how average household incomes changed, adjusted for cost of living, which illustrates both points:

This shows that household incomes were level at first and then dropped steadily for the 22-30 age group until a year ago and then rose. For the 31-59s the squeeze levelled off at the end of 2011 with a gradual rise since. The over 60s have not done so badly, depending on how you measure their cost of living. Individually many people may be better off (things have get better as we advance through the age brackets), but overall the country has not recovered its economic standard of living.

The Labour narrative runs something like this. The economy was hit by a global financial crisis while they were in power, but a rapid fiscal response limited the damage. Measures included a temporary cut to VAT, as well as maintaining benefit levels, and, of course, a big bailout of troubled banks. In 2010 the Coalition took power and cut back these fiscal measures prematurely and increased taxes, causing standards of living to plunge, with only an anaemic recover since. Labour spokesmen claim, and their more partisan supporters fervently believe, that the government’s austerity has been a disastrous policy mistake, especially for the worse off. There is also a claim that the rich have escaped the pain and inequality risen.

The coalition counter-narrative is that the crisis in the first place was Labour’s fault, through profligate public expenditure and lax regulation of the banks. And the fiscal measures after the crash came at a staggering public cost, with a deficit of over 10% in 2010. This was unsustainable, and the current government’s austerity policies have saved the country from huge levels of debt and a huge future tax burden. If the recovery was anaemic, that was because of deeper weaknesses in the British, European and world economies. Now these weaknesses have been largely overcome, we are doing very nicely thank you. And a previous IFS study has shown that inequality has actually fallen, with the richest 10% paying a greatly increased fiscal burden – though admittedly things have been tough for the young and poor.

What to make of these competing narratives? I think the coalition argument is closer to the truth, even if they play up Labour’s mismanagement a bit more than is fair – not so much because there wasn’t severe mismanagement, but because that insight comes mainly from hindsight. But I’m biased and many learned people think that Labour’s narrative is in fact fairer. There is no decisive way of resolving the conflict, which requires the building of counterfactuals with economic models that are deeply flawed. But that’s the past and the important question is what is the best thing to do now.

And the answer to that question must start with this fact: the British economy is displaying a striking level of weakness. Three signs of this are worth drawing attention to. First is the lack of economic productivity growth. The IFS makes much of this. Employment levels are quite healthy, but this has not led to the levels of production that it should – which means there is no money to pay people more. Economists have been stressing about this for some years now, but they have not provided a clear analysis of what this is all about. Personally I think a lot of it comes about from the diminution of the finance and oil sectors. The former’s high level of productivity was in fact a mirage; the latter is trying to make the best of ageing oilfields. I also think there is a wider issue in all developed economies, as we transition to a world where improved wellbeing does not depend on higher levels of consumption – which used to be the motor of economic growth.

The second sign of weakness is more concrete. Our trade balance, which was strongly negative before the crisis, is not getting much better, in spite of a weaker pound sterling. This is strikingly different from the previous recovery from a recession, in 1992 – when a trade deficit was converted to a surplus quite quickly, and was the first part of a period of continuous growth that lasted until 2008. Martin Wolf, the FT economics commentator, has said that in the Euro zone an adverse trade balance was a surer sign of trouble than a fiscal deficit. He seems more relaxed in a UK context, but I think it is highly significant. The country is living beyond is means, and has not solved the problems that led to the 2008 crash.

The third sign is closely related – the other side of the same coin. The vaunted recovery is mainly led by increased consumer demand rather than increased investment. The public (as well as the government) is trying to borrow its way out of the crisis. A strong level of investment would lead us to be more relaxed about a trade deficit – but this is not the case. Investment is recovering, but not by enough. And levels of debt remain stubbornly high.

A lot of the problem is actually beyond the control of any government. It is down to the freely made choices of individuals and businesses, and changes in technology, not just here, but in the countries we trade with. But we do need our politicians to be on the case.

The Conservatives are unwilling to acknowledge the current level of economic weakness. They keep talking about their long-term plan for the economy, but this mainly boils down to further austerity, mainly cuts to expenditure, to bring government finances onto a more stable footing. They hope that private sector investment will pick up, and focus on things that will improve efficiency and wellbeing, rather than the merry-go-round of property prices. But further austerity will cause public investment in infrastructure to suffer, as well as education. Further, the party wants to “renegotiate” the country’s relationship with the European Union and put membership to a national referendum. The country’s international standing has already been a victim of this policy. Since so much of the country’s fate depends on the wider world, this is sheer folly.

Labour gloat about the current weakness of the economy, but have few answers. I have not heard a Labour spokesman willing to talk about increasing the economy’s productivity. They have ideas to tackle some of the symptoms, like raising the minimum wage to deal with low pay, but have no answers for the disease. And the party lacks a unity of purpose. Its left wants an end to austerity and attack on private business bosses; others talk of devolving power from the centre but have little understanding of what this really means. They do not look like a coherent government in waiting.

Meanwhile there are plenty of things we should be talking about. Encouraging weaker local economies to develop without permanent subsidy from the centre; choosing the right public infrastructure investments; developing a more complete and rounded education of our children and young people; working internationally through the EU and other institutions to tackle multinationals and tax evaders. But these do not reduce to bite-size policies and 140-character debates. So we will keep banging away at the unwinnable blame game.