It looks certain that Liz Truss will become British prime minister this week, and British politics will take a dramatic turn. It is surely an act of political suicide by her Conservative Party.

We are, of course, urged not to underestimate Ms Truss – as so many of us have in the past. And yet, Matthew Parris in The Times tells us that this is a mistaken sentiment – just as it was for Boris Johnson and for Donald Trump – also politicians who won the top job against huge scepticism of their fitness for the job. She really is as shallow and dangerous as she looks.

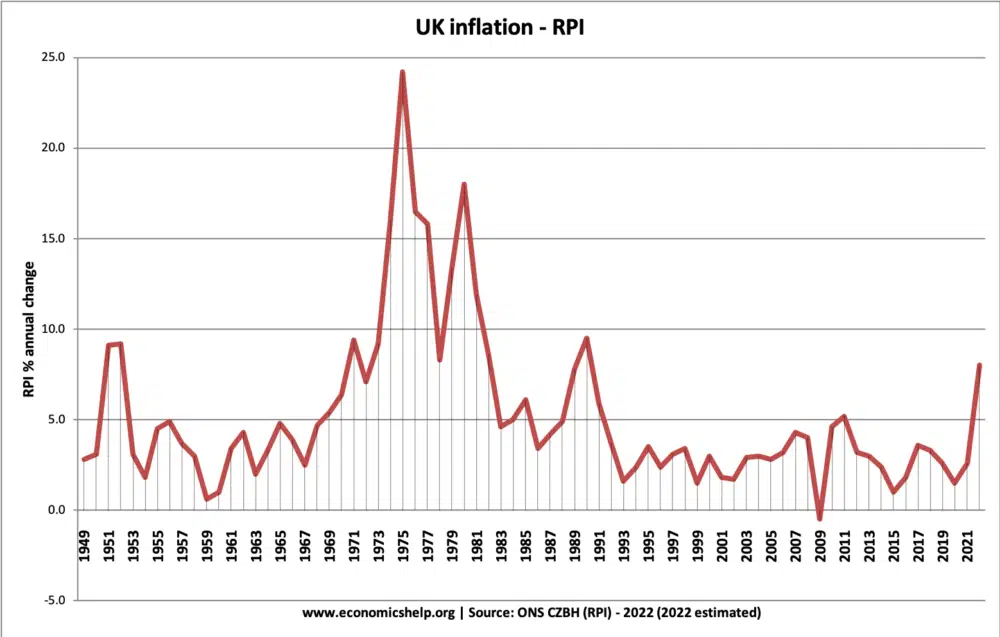

I agree. During her bid to persuade first Tory MPs and then ordinary Tory members to vote her into the job, she has backed herself into a difficult corner. Her fiscal policies are inflationary; her economic ideas delusional, and she has shown little aptitude for the negotiation and compromise that are essential to any successful political leadership. She is also a stiff and awkward communicator. She enters the job in the middle of an economic crisis – it is hard to see that she has much chance of a honeymoon period longer than a month.

It gets worse for the Conservatives. They have built their political appeal on the basis of being a safe pair of hands with the economy. Whether this claim has been justified is another matter: while the austerity policies with which the party was associated from 2010 until 2019 struck most voters as being careful and sensible, most economists regarded them as being inappropriate at best. Now that reputation for economic competence is under water. Recent polling shows a Labour lead on handling of the economy, as its does in overall voting intentions. This is very dangerous territory for the Conservatives – and Ms Truss is going to do nothing to improve it. The sort of tax-cutting fantasies that are popular on the American right do not play so well with floating voters here. And it is hard to see that inflation is going to improve much under her stewardship – not without a recession, which she is claiming that she can avoid.

Still, many observers think the Conservatives can pull things back. Ms Truss will hit the ground running, as she has had plenty of time to prepare. A new cabinet will be put in place quickly – and the current government lethargy will be replaced by energy and optimistic talk. There is bound to be a honeymoon bounce. Ms Truss might even go straight into a new general election. This would be perfectly justifiable, to give her a fresh mandate, rather than the flawed manifesto of 2019. The Conservatives have been planning for this possibility for some time, as new, and more advantageous constituency boundaries come into effect. They will likely be better prepared than they opponents. But the polling looks dire – and she and all her hangers-on will be dismayed at the idea of throwing away their coup so soon. Opposition is a dismal place to be for those used to government. Still there is a certain recklessness about Ms Truss, and I wouldn’t rule it out.

The main reason that people seem to think that the Conservatives might win the next election is a lack of belief in Sir Keir Starmer, the Labour leader. He is uncharismatic and cautious. It is hard to say what he stands for, and his polling is weak. But is this a Westminster bubble thing? Activists on the left like their leaders to be charismatic and radical – and so do the journalists and others who follow them. It is easy to see their disappointment. But FT columnist Janan Ganesh warns that this bias against the uncharismatic, also applicable to US President Joe Biden, leads us to underestimate them. Floating voters like their leaders to be reassuring and middle of the road – and, I would add, especially if those leaders are from the left. Radicalism is not a positive attribute. The Conservatives are walking into a trap.

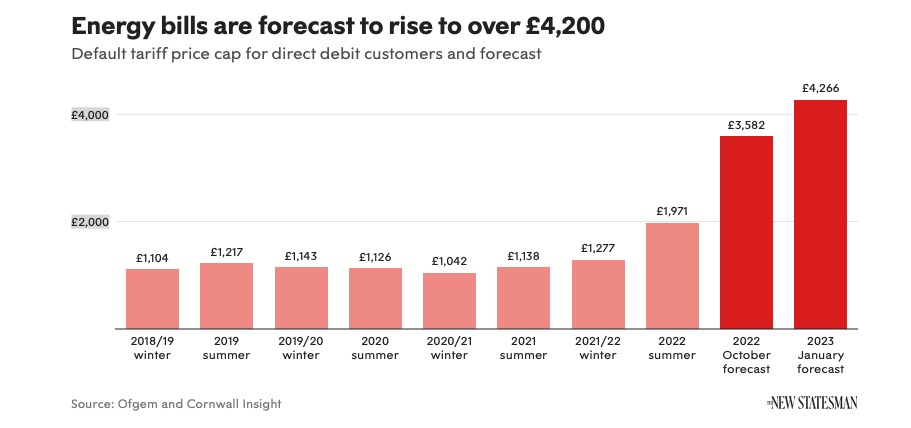

The main equation for Labour is whether they will win the next election by themselves, or alongside the Liberal Democrats. The Lib Dem leader, Sir Ed Davey, is no more charismatic than Sir Keir, though he is more experienced. He has made a lot of the political running in the last few weeks on the energy crisis – a subject he knows well as a former Energy Secretary. Like Sir Keir, he is relentlessly un-ideoligical. He is not trying to move the debate to the areas that his activists want to talk about – such as Brexit – but focuses on the areas that are close to floating voters top concerns. The other issue that the Lib Dems have been able to run with is the water companies’ disposal of raw sewage into rivers and the seaside. The Lib Dems are doing well in many Tory heartland seats where Labour is weak. The public ground is being subtly prepared for a coalition – or cooperation at least – between the two parties – in a way that it wasn’t before the Lib Dem coalition with the Conservatives in 2010, which saw Lib Dem support collapse.

It is reported that the Conservatives are preparing a campaign based on defeating the “Coalition of Chaos”, compared with strong and stable one-party government. This follows the successful deployment of this line of attack in 2015, which nearly wiped out the Lib Dems – though it failed in 2017, to the extent that the Tories are likely to avoid the slogan “Strong and Stable”, the basis of the 2017 flop. This line might gain traction if it looks as if a Labour-Lib Dem alliance will not gain enough seats to prevent the Scottish Nationalist Party from holding the balance of power. The SNP will not want to let in a Conservative government, but they will demand another referendum on independence. Labour and the Lib Dems are going to need to think through their strategy on that front with care, and not just hope that the issue won’t come up. But will the prospect of another Scottish referendum scare English floating voters? Probably not enough.

Sir Keir’s strategy was a risky one. He has done nothing to motivate his own activists – and gone out his way to insult the socialist left, the source of Labour’s most energetic supporters. He is unable to project the flair of Tony Blair, who previously made a floating-voter strategy work for Labour. But the Conservatives are playing into his hands.

I am going to be offline for two or three weeks.