I’ve been offline for three weeks, but remarkably little has changed in Ukraine. The Western powers have followed my advice about the scale of assistance to Ukraine. I also suggested that the West place pressure on the Russian-controlled territory of Transnistria; tension there is indeed rising, but not as the result of Western actions. Meanwhile Liz Truss, the British Foreign Secretary has been upping the rhetoric about the scale of defeat she wants to inflict on Russia. This is fluff from somebody talking to Conservative Party grassroots before a potential leadership election. But it poses a more serious question: what is the endgame?

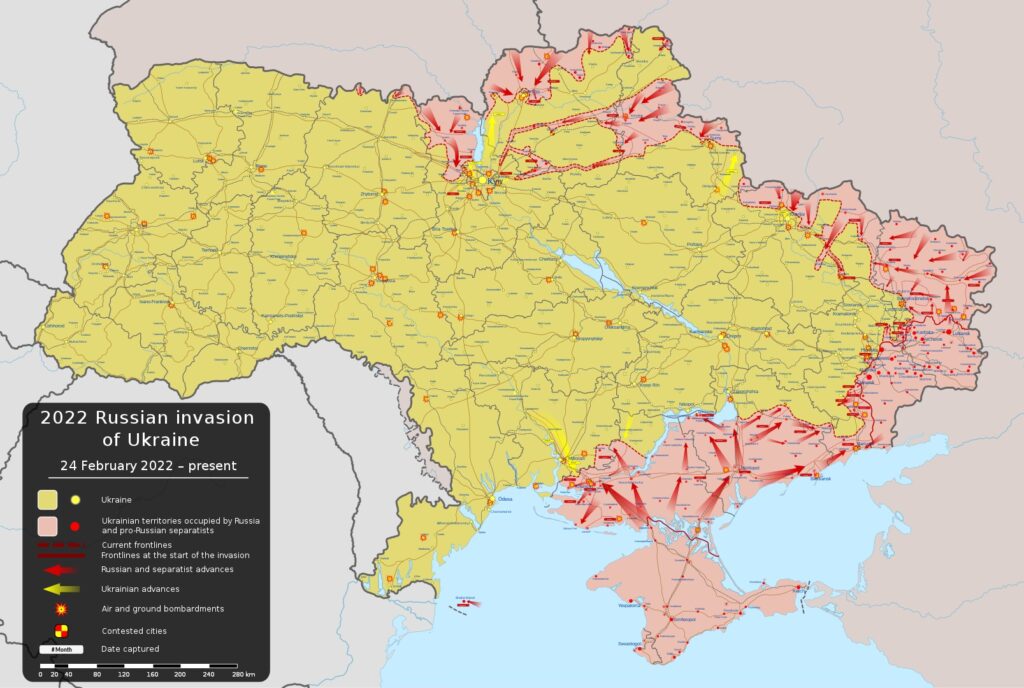

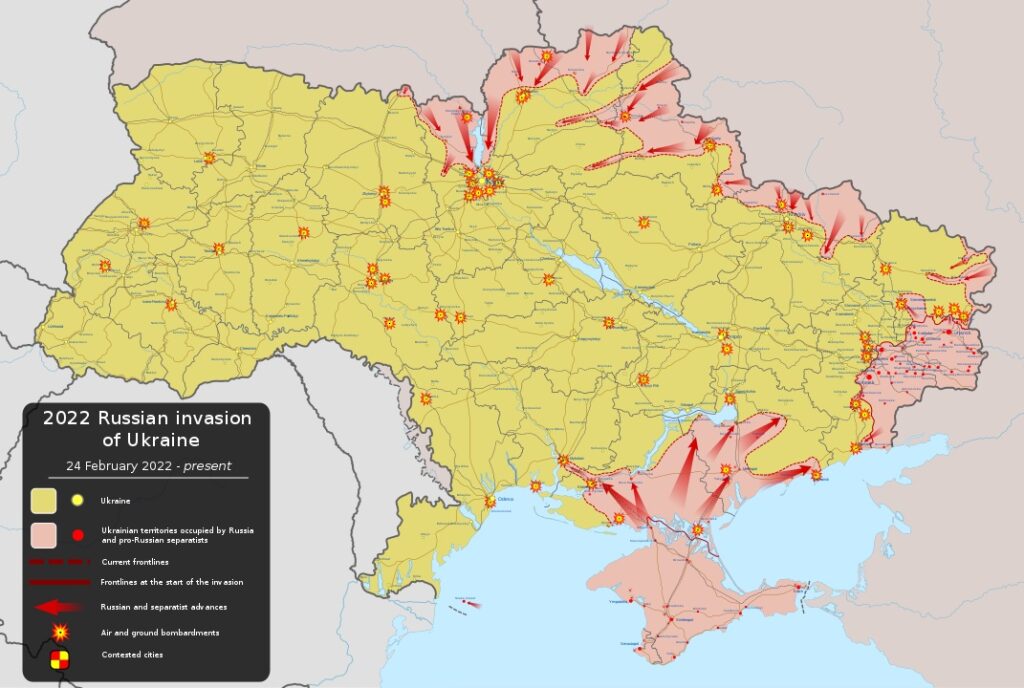

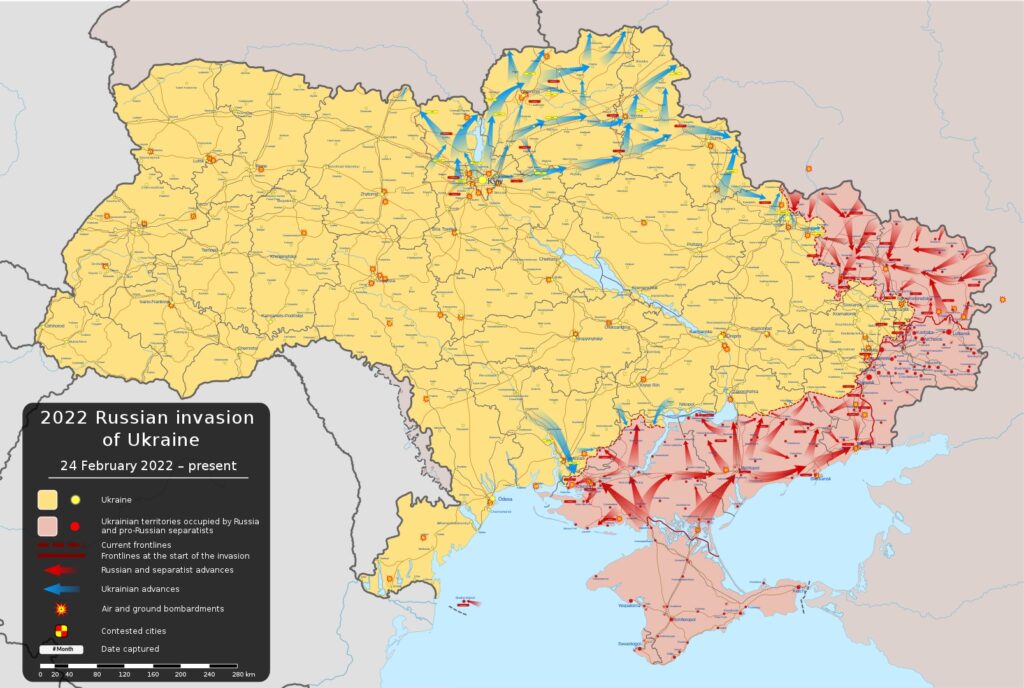

On the ground, meanwhile, little has changed. Russia continues its assault on Donbas, but has so far gained little territory, though it is making slow progress on one of it axes of advance. The battle for Mariupol seems to be nearly over, but further drama is assured with the fate of Ukrainians holed up in the Azovstal steelworks. Elsewhere Ukraine has nibbled some territory back, notably around Kharkiv. Once again the some of the expert military commentary in the media is well off the mark. It was suggested that the more open terrain in Donbas would lead to tank battles more reminiscent of the the Second World War (notably the great battle of Kursk in similar terrain nearby). That is nonsense – technology has changed the way war is fought. Instead the battles seem to be turning on artillery. The Russians do not want to press beyond the range of their low-tech artillery forces; the Ukrainians need to resist continuous bombardment, and strike to back at the enemy artillery if they can. This makes warfare slow-moving, unlike those battles of an earlier era.

Events in Transnistria (the thin sliver in the east of Moldova on the map) are a bit of a puzzle. Grenade attacks on Russian facilities there have been reported, without casualties. The Ukrainian government suggests that these are false-flag attacks designed to give Russia the pretext for involving its garrison in an attack on Ukraine (it is close to Odesa). This doesn’t make a great deal of sense. The Russian garrison is weak (reported as 1,500 men) and difficult to supply. It is surely more useful to the Russians as a source of signals intelligence and such without direct involvement. It is more likely that Ukraine is taking a leaf out Russia’s book and preparing the ground to carry out a “special military operation” to neutralise the Russian garrison. That would be a major humiliation for Russia, given the history of the place.

My earlier analysis was that a stalemate in Donbas would continue until something broke – by which I meant that physical or morale losses, and or logistical strains, cause a dramatic collapse on one or other side. That still seems to be true. Ukraine has longer supply lines than around Kyiv, and Russia is trying to attack them with air power and missiles. Russia’s army is badly mauled and shaken, and it is using prodigious amounts of munitions, though its supply lines are more secure than in the battle for Kyiv. It is hard to tell who will break first or when, or, indeed, if either will. Conflict at the current intensity is not sustainable in the long run though.

A Russian victory would see Ukrainian forces giving ground in Donbas, with the probability of a substantial number of troops being surrounded. Russia would take control of the two Donbas oblasts, plus the southern ones of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia (or most of the southern portion of the latter). This would fulfil one of its stated war aims of “liberating” Donbas, as well as securing Crimea, including its water resources. Russia would dearly like to add Odesa to this, but it might choose to stop there. It would then enter peace talks with the ever-present threat of continuing a low level war that might be escalated. Any peace would result in a formal partition of Ukraine, with effective Russian control of its new conquests. This would be enough for Russia to claim vindication, though in fact its main war aim of “den-nazifying” all of Ukraine would not be met in most of the country. Parts of the Ukraine that the Russian leader Vladimir Putin regards as core Russian territory would have been turned into hostile ground for the foreseeable future. And NATO would have been greatly strengthened, while Russia’s own forces would require many years of rebuilding.

I don’t think this outcome is very likely. Russia’s resources are not limitless, and the damage inflicted on its armed forces is very severe. While its strategy of attacking Ukrainian infrastructure is militarily sound, it lacks the precision munitions and air capability of doing it in the way the Americans managed in Iraq, for example. The West is providing more and more logistical support, and Russia has few good options of doing anything about this – just as America couldn’t stop Soviet and Chinese support in Korea and Vietnam, which went substantially further than the West is doing now.

What would a Ukrainian victory look like? A dramatic collapse of Russian logistics and morale is possible, but not very likely. More likely Russian efforts will slacken and resistance weaken, allowing Ukrainian forces to slowly start biting bits of tis territory back. But this is unlikely to take them any further than the post-2014 frontiers. After this the Russian defensive infrastructure will be too strong. At this point America might offer Russia sanctions relief if they agree to settle. But any substantive settlement, even based on these borders, would be very humiliating for Mr Putin, and it is hard to see him accepting it. He would have to be removed through a coup from the security establishment, unable to countenance the war continuing. But Mr Putin takes his personal security more than seriously.

Meanwhile the Russians are taking steps to consolidate their control of the territory they have acquired, with the “filtration” of the remaining population, the creation of local government structures and the adoption of the Russian rouble. They are trying to find ways through the Western sanctions for militarily useful supplies, using third nations. There is also speculation that they will escalate the conflict into a full war, allowing full mobilisation. The damage to Russian military capability runs deep, though, and large numbers of conscripts won’t help. But it would show that Russia is preparing for a long haul. This would require the West to extend sanctions, potentially upsetting neutral countries. And then winter would approach with Europe’s gas supplies under threat.

What happens next depends on what happens on the ground. If Russia can complete its conquest of Donbas, it is possible that Ukraine and its backers will reluctantly accept a tactical defeat. If Ukraine can recover Kherson and Mariupol, they, and their backers, may feel they have done enough to settle, and Russian political will might crack. Neither possibility looks at all likely in 2022. Which means a long haul. The military intensity of the conflict will reduce, as both sides seek to regroup. It then becomes a battle of political wills, in Russia, Ukraine and amongst the Western powers, especially America and Germany.

That is a grim prospect for the Ukrainian people, especially if they have homes in the east and south of the country. One reason that nobody should start a war is that they are so hard to stop. The world did not need another lesson the futility of war – but that is exactly what Russia has given it.