So far in this astonishing episode, the world’s financial systems have held up well. Remarkably, lessons have been learned from the Great Financial Crisis, both in the behaviour of policymakers, and in the resilience of banks. But many claim that the Euro is especially vulnerable. Are they right?

The crisis so far has not been good for the egos of the Europocrats. The response has been led almost totally by the governments of its member states. It turns out that the EU really is just a free trade area after all. When something more important than trade comes along it has nothing important to do. And when its leaders at last got together to sort out a financial response, the outcome was pathetic, and spoiled by the sort of bickering shows that there is little solidarity amongst the member states.

Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister, called this out on BBC Radio 4. The most important part of the EU’s infrastructure, the Euro, has turned into an instrument of oppression. The rich northern states, notably Germany and the Netherlands, were vetoing any serious aid to the most afflicted states, such as Italy and Spain, while not allowing them to help themselves. He said that German leaders should level with their public: the Euro was really good for their economy, but to keep it going they needed to be more generous to other members. The Italians, in particular, are throughly disillusioned and could provoke an existential crisis for the zone.

There is plenty of truth in what Mr Varoufakis is saying, but nobody should bet on the dissolution of the Euro just yet. Critics of the system miss two things. Firstly, as this week’s Buttonwood column in The Economist has pointed out, the European Central Bank (ECB) has learned a lot from the previous crisis and has now become the EU’s most effective institution, and not bogged down by the bickering that undermines the more overtly political arms. It has, amongst other things, rushed to buy up debt from Italy and Spain, thus greatly assisting a strong fiscal response to the crisis. This has the effect of mutualising their debt by stealth. The ECB has learnt the art of doing just enough to keep the Euro going, while being unable to fix its deeper flaws.

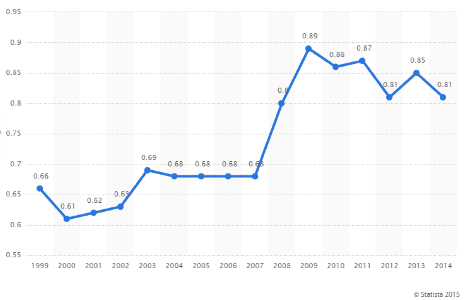

The second point is more subtle. It is wrong to suggest, as Mr Varoufakis does, the Euro is in effect a plot by Germany to rob Italy. It is better understood as a conspiracy between German workers and Italian savers. The Germans get plentiful and secure jobs, because their currency is held down, allowing its industry to run a surplus. Italian savers get more buying power for their money in a currency that is stronger than their own would be, with less risk of inflation. The victims are Italian workers, whose firms struggle to make progress with such a strong currency, and German savers, who lose buying power. It is arguments between these victims that drive the acrimonious politics of the Eurozone. Politicians like to blame an outsider, so German ones like to blame lazy Italian workers for low returns by their savers, and Italian ones like to blame the Germans for screwing their businesses.

So the Euro’s losers drive the day to day politics, but as soon as it looks as if they might succeed in their goal of causing the collapse of the Euro, the winners, German workers and Italian savers, hoist it out of trouble with a twitch upon a thread. The clearest example of this is Marine Le Pen’s tilt at the French presidency. Her bid featured resentment at the Euro, and it got her into the final round against Emmanuel Macron, but it rapidly collapsed when, in one of the debates, she floated the idea that France might leave the Euro. French savers, many of them older voters sympathetic to Ms Le Pen’s anger at liberal elites, suddenly realised that there could be a cost to their protest and deserted her. Something like this effect will happen in Italian politics if anti-Euro politicians get too much traction there.

So the Euro is safe but the politics is grim. What is needed are two things: more enlightened self-interest from northern leaders, and more willingness to embrace economic reforms by southern ones. The big trading surpluses by northern countries mean that they could easily be more generous to their southern neighbours by buying their goods and services or through direct aid (though lending them money simply builds trouble for later). Each of the southern economies has economic inefficiencies that their leaders should do more to tackle. In Italy it is excessive petty regulations to protect economic vested interests. In Spain it is lack of labour market flexibility. In Greece it is a failure to collect enough tax, especially from the better off. Until they tackle these they will always be supplicants and politically vulnerable.

For all that, the Euro has some very challenging times ahead (as do the US dollar and the Chinese Yuan, for differing reasons). Italy could easily be faced with a banking crisis, at a time when the attempts to mutualise banking risk across the Eurozone are incomplete. The acrimony will continue.

And this will set the EU on a trajectory that makes it more and more resemble the Holy Roman Empire. This was a tangle of German states, led by an Emperor with little practical authority. It was much despised by Enlightenment thinkers, and finally brought to an end by Napoleon. But it was the foundation of the strong commerce and devolved administration that makes Germany (and Austria) such successful states today. This is something Anglo-Saxon observers almost never understand.