After a series of catastrophic election results, the Liberal Democrats

are indulging in some deep thinking about the party’s future. The one silver lining from the party’s disasters is that it is left with the nearest it will ever get to a blank slate on which to rewrite what the party is.

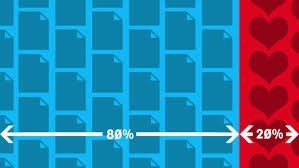

Into this debate comes an important pamphlet. The 20% strategy: building a core vote for the Liberal Democrats by former Cambridge MP David Howarth, and inveterate blogger Mark Pack. I would urge anybody interested in the party’s future direction to read it. The jumping-off point is familiar to anybody that has followed the party’s internal debates. Critics of the party’s leadership (especially under Nick Clegg) suggest that the party neglected the build-up of a core of loyal supporters who would vote for the party come what may. This core now stands at something like 5%, and is much lower than that enjoyed by the Conservatives and Labour, or the SNP in Scotland, and is being challenged by the Greens. Instead the party chased the floating voters of the “centre ground”. But instead of articles sounding off in Liberator magazine, this pamphlet is altogether more serious. It starts with a real attempt to look at evidence, and moves on to a concrete set of proposals.

The authors believe that the party is held together by shared values, rather than class identity or nationalism. These values are shared by about 35% of the country – those who display openness, tolerance and internationalism. That 35% figure comes from a polling answer to a question about immigration. From this the authors reckon that a 20% core vote is feasible. There is some interesting analysis of that 35%. It leans left, tends to be female and is ethnically diverse. It isn’t hard to see how the party’s appearance of being white, male and in coalition with the Conservatives got in the way of building that vote.

So what to do? I would urge readers to read the paper – there are many facets to their action plan. They want the party to formally adopt a core-vote strategy, and to establish a national campaigning infrastructure to focus on this, to complement efforts to build the local government base, and winning parliamentary seats. This national level of campaigning, led by an elected Deputy Leader, would build up the party’s vote for proportional voting elections, of increasing importance to the party, and provide a home for supporters not lucky enough to live in one of the areas where the party is active locally. This national campaigning would focus on issues that demonstrate the party’s values – go to places that other parties cannot. Paddy Ashdown’s stand on Hong Kong and Yugoslavia are quoted as past examples of such campaigning.

I can see this paper and its proposals being very popular in the party. They make a lot of sense. There is something for everybody. I particularly like its realistic assessment of local parties in areas where the party is weak. So often the party’s campaigners have glib answers to the challenges. “Just set up a target ward and grow from there,” they say. I am happy to support the paper myself.

But it is all too easy. The authors point out that a core vote strategy is hard, and that the party has failed in its many past attempts. That tells me that something big has to change; a lot of received wisdom has to be put on the scrapheap, and a lot people in the party are not going to like it. It is not just a matter of adding another strand of campaigning, and then tweaking the party’s internal processes here and there. The danger is that everybody will assume that all the changes in behaviour apply to other people, and they will continue to do what they have always done, with a bit of judicious relabelling.

But succeed in cultural change such a big change you need to have a flaming row, and annoy some people a lot. If need be such a row has to be provoked artificially. The one successful political transformation achieved in recent times in Britain was by Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Peter Mandelson to the Labour Party in the 1990s. They theatrically replaced Clause 4 of the Party’s constitution to show they were serious – rather than just ignoring it. Contrast this with David Cameron’s attempt to transform the Conservatives, where he was careful to avoid such rows – with the result that the party never really changed (or not not in the direction he favoured). Only now are there signs that he and George Osborne are ready to make genuine cultural change for the party, towards economic liberalism, with EU referendum being the chosen field of conflict. Even worse was Ed Miliband’s attempt to move the Labour Party to the left while maintaining party unity, which left the party in a terminal muddle. So if a cultural change requires a degree of conflict, where will conflict need to be invited if the Lib Dems are to make a success of a core vote strategy?

The first place is in what the pamphlet calls the three pillars of campaigning: local, parliamentary and national-core vote. In their vision these three happily coexist. But they also compete. In the Kennedy years the party brilliantly built up its parliamentary base – but at the expense of brave national campaigns to demonstrate core values. The exception was the the party’s stand on the Iraq War; but Charles Kennedy had to push for that in teeth of advice that rocking the boat would not be good for the party. Parliamentary and local government campaigns depend on winning over floating and tactical voters (“It’s a two horse race” and a bar chart are almost compulsory in Lib Dem election literature). Strong national campaigning is likely to upset those voters and the activists trying to woo them. The party is obsessed with winning electoral contests; that obsession must be loosened if a core vote strategy is to take root. It must recognise the idea of good losers – candidates who did not come first but built up members and long term voters. This concept is so alien to the party’s campaigners that they will not take it seriously. This is why the idea of these values campaigns being led by an elected official with a separate mandate (whether or not Deputy Leader) is a critical element of the overall plan.

So campaigning is likely to provoke conflict, but it is not an easy place to have a theatrical row to demonstrate that the party really has changed its spots. That may arise from political strategy. Political strategy is about how the party intends to use its assets, especially seats in various representative bodies, to further its aims. For a liberal party that must mean working with other parties – rather than throwing rotten tomatoes from the fringes. To date such political strategy has been left to the leadership, and not spelled out clearly to electors and debated amongst the wider membership. At parliamentary level the declared policy is to work with the largest of the main parties to form a coalition in a hung parliament. But it matters a lot to voters and members which party or parties the the Lib Dems choose to work with. That is one reason why their vote tends to drain away in election campaigns when a hung parliament looks likely. In this year’s election the party’s stand contrasted with the Greens, the SNP and Plaid Cymru, all of whom said the would not work with the Conservatives.

But the party’s campaigners hate to take sides – they see that it will upset groups of voters they are wooing, and so make winning marginal seats that much more difficult. When the question was put to the two leadership contenders at the London hustings, neither said that the party should change its position of working with either of the main parties. That surely has to change. It makes the party look opportunistic and transactional – only interested in the status of power, rather than principles. This was the most wounding criticism of the party while it was in coalition. The party, after debate and consultation with members, will need to say that it will not work with a Conservative-led government (the party may accept Tories as junior partners…). In due course we might contemplate electoral pacts in order to promote an agreed programme of political reform. Labour is the competition; the Tories are the enemy. And I say that as somebody from the right of the party that loathes the Labour party, and has more sympathy with the Conservatives than most.

I do want the Liberal Democrats to want to be a clear and effective political voice for the 30% of so of the electorate that is open, tolerant and internationalist. I also want it to champion reforms to politics, public services and economic management that place sustainability and wellbeing at their heart, rather than money and vested interests. David Howarth and Mark Pack point to some useful next steps. Necessary, perhaps, but not sufficient.

Excellent analysis. Your penultimate paragraph I completely agree with!

The Strategy is right but there is no reason that this and a Target strategy for FPTP cannot work in tandem.

I would agree that the party still needs to target to achieve electoral success at parliamentary and local level – which means drawing in non-core voters. It is interesting to note that Kennedy’s stand on the Iraq war did not, in fact, hurt the party’s standing in parliamentary elections – 2005 was the best ever. It’s more that focus on marginal votes makes leaders risk-averse – and neglect other objectives for the party.

While I do not pretend to be very knowledgeable about all things Liberal, and also being very new to the party , I suspect that it is not just campaigning that is the key to recovery, esp in Scotland.

I would never have joined the party had Nick Clegg remained as leader, he didn’t come across well ,and he diluted the Liberal message to chase the middle ground, failing to undertstand that the coalition with the Tories was seen as a huge betrayal in Scotland. Add in the Better Together campaign, and standing on the side lines when Cameron and the right wing press where campaining on an anti Scottish ticket was a disaster. The message that we will not work with the SNP said to Scots that they were second class, that their vote did not count, and that they could not be a part of decision making in what is supposed to be the United Kingdom. What an utter disaster of an approach and was seen rightly by many in Scotland as coming across as racist. It was also as far from Liberal as you can get. The really sad part for myself as a new member is that I don’t think Willie Rennie is learning the lesson and the elections next May will be a disaster.

In my humble opinion, and for what it’s worth, I think that we have to get credability again in Scotland and that means being honest, no SNP bad rubbish, no cheap shots for the sake of it. We have to be grown up and move away from the politics of envy and hate. We need to be seen to be a credible voice in Scotland where we campaign on a Liberal agenda that has Scotland at it’s heart and is done with honesty and dignity. It’s not just about how much we put into it, yes that’s important, but not as important as the message and how we put that across.

We have to be seen as a grown up and mature party that will always do what’s right and will not look to be in coalition with anyone but to govern and to lead. If coalition is the result of electoral success on our own terms then fine, but we have to be clear on what we stand for and what we don’t. It’s a long way back in Scotland, I can’t pretend to really comment on England that much, but if we want to survive let alone recover we need to change.

Bruce

Thanks Bruce – I’m always intersted to hear a Scottish perspective. I’m not close enough to Scottish politics to comment on Lib Dem behaviour there – though I think a recovery in Scotland is vital for the party. But what you describe sounds like a classic conflict between a “winning seats” and “core vote” strategy. My take on the party in the last election was that we wanted to rally the anti-SNP vote to get Labour and Tory tactical voters. And yet many of our core voters are sympathetic to the SNP. There is a liberal critique of the SNP, and I would have thought the party should stick to that – but be prepared to work with the SNP where there is agreement. This is not a formula for winning seats in Westminster, but that shouldn’t be top priority right now!

I have re-joined after a break of 4 yrs . I left because of the local scene (Tories & Labour out community campaigning the Lib Dems ie – Lib Dems not doing it!! IMO) not the Coalition which was an evil required.

We MUST get our own house in order ie stop the cash for Peerages etc, involve members in policy making not just conference reps. Basically – say what we mean – mean what we say. I’d rather be part of a honest ,financially poorer, smaller

Liberal party than one not being quite as bad as the others.

Any party core vote has to be built on values, not class or geographical identity (like the other parties). This may mean fewer seats and smaller donations in the short term.

This reminds me of some of the conversations whilst I was a member, perhaps 8 or so years ago.

There was much consernation over the lack of air-war – no overarching statement of principle, just the ground-war of local campaigning…

Interesting. The interesting question is whether the focus on local campaigning made the party reluctant to be too clear on national messaging. There was certainly a widespread feeling that national campaigning was not cost-effective – part of the cult of targeting.

Excellent piece. Mark and David’s work is very valuable. There is also a generational difference here. I see it in my own children who are every bit as liberal as their parents on social and environmental matters but significantly less trusting of the state and large bureaucracies. In many ways more “liberal” than those of the Alliance and merger generations.

While 2005 was the high watermark of our electoral support we need to be careful in our analysis as to why. Many former Labour voters perceived Tony Blair as having let them down over the Iraq War and as being “not left wing enough”. However Labour’s own polling said they would return to Labour once Blair went. Indeed that happened most notably in Scotland and London despite Labour’s national vote share falling significantly between 2005 and 2010.

Polls have shown over very many years that the Lib Dem vote is the least loyal and rooted of the main Parties (and indeed is significantly less loyal and rooted compared to UKIP or the SNP). This is not simply a reaction to our participation in the Coalition.

Other values based analysis of people’s instinctive political allegiance shows we are in direct competition with Labour and the Greens for those who occupy “the 35% space”.

Community politics that understands that “community” in the 21st century is more than geography also has a key role to play in rebuilding our Party. Participation in politics as reflected in voting and membership of Parties is in serious decline. Engaging with people, their communities and on their core concerns is vital.

Finally we require a coherent economic approach. Revisiting mutuality, co-operation, social entrepreneurs and responsible capitalism will be kkey to that development.