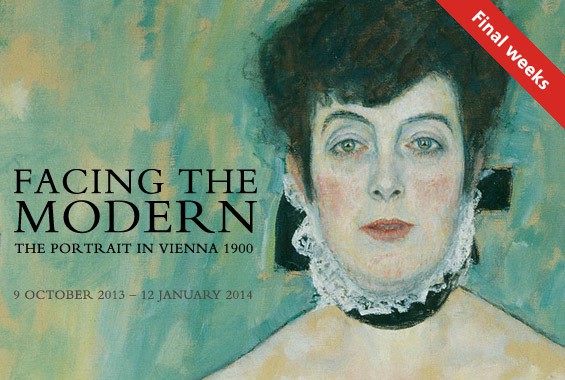

Today we went to see the last day of the National Gallery’s exhibition of portraiture from Vienna at the turn of the 19th/20th Century. The art was interesting in its own right, but the main impact for me was learning about the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which lasted from 1867 to 1916, and its implications for our time.

Austria-Hungary came into being after the Habsburg Austria Empire’s disastrous war with Prussia in 1866. This put to an end idea that the Habsburgs would lead a united Germany. It also put paid to the Austrian Empire’s possessions in Italy, which joined the new Kingdom of Italy. Austria’s rulers had to consolidate what they had, and they took a distinctly liberal approach. The Kingdom of Hungary was established as a parallel entity to Austria, rather than simply being part of Austria’s extensive possessions, and it took perhaps about half of the total land area. Hungary included what is now Slovakia, Croatia and the Transylvanian region of Rumania. In each part of the dual monarchy, democratic reforms were enacted, with elections and citizenship open to all (I think these were more advanced in Austria than Hungary).

Many people of different backgrounds migrated to Vienna, which became a liberal, multicultural place. Jews, in particular, were offered a route into the higher echelons of society, and many assimilated into the Austrian culture. But by 1900 all this liberalism was creating a backlash, and tensions started to mount. There was political stalemate, broken by the First World War in 1914 – which Austria-Hungary itself started, by attacking Serbia. This brought catastrophe down on the Empire, which broke up after Emperor Franz Joseph’s death in 1916, with complete dismemberment when the war finally ended in 1918. Things got worse after that, with anti-Semitism growing into the horror of the Holocaust. Hitler was an Austrian and part of the Vienna scene before 1914. The betrayal of Jews, in Austria especially, has left a stain on Europe’s history that will never be expunged, to rank alongside exploitative, racist colonialism, which Austria at least did not take part in.

Austria-Hungary was widely disparaged at the time – “the sick man of Europe”. Its attempt to forge a multicultural national entity was thought to be undemocratic and illiberal. The right way was to form nation states from largely one language and culture. Nowadays we have much more sympathy with the Austria-Hungary project. National identity is a complicated business, and the idea of creating states based on linguistic and cultural heritage proved to be romantic fiction at best, and licence for oppression, murder and war at worst. All European nations wrestle with the issues of being home to multiple cultures, and we have created a vast, multi-national entity in the EU, which shares many features with Austria-Hungary.

What the Exhibition showed, however, was that for all the tension and ultimate political failure, Vienna in particular produced a flowering of creativity. Many of the period’s greatest artists worked there (we can think of Gustav Klimt and Gustav Mahler, and the highly innovative Arnold Schoenberg). This creativity was not confined to the arts: there was Sigmund Freud, and in the discipline of economics, Joseph Schumpeter, each responsible for ground-breaking ideas that we now take for granted.

But there is a discomforting parallel with Europe today. The European liberal and multicultural project is under fire. Nationalist groups, promoting intolerance, seem to have the political momentum. This is creating a tension, and causing liberals to doubt. In Britain it is disheartening to see that both Labour and Conservative parties have decided to pander to the anti-liberal momentum, rather than stand up to it. And meanwhile, just as in the 1900s, economic advance seems to create inequality, creating yet more tension.

Are we heading for disaster? I don’t think so. The horrific events of the first half of the 20th Century still cast a strong shadow. But liberalism does need to reinvent itself. I dedicate myself to that cause.

It is not widely known that this proposal:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_of_Greater_Austria

for a federal Austria-Hungary.. a mini-EU… had as one of its main supporters, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand… what might have been…

Thanks Christopher. This is fascinating. An attempt to give multiple linguistic identities real power, while upholding basic standards at federal level. As I understand it there was a real tension between the essentially liberal Austrian approach to multiculturalism, and the Hungarians, who opted for oppressive, forced assimilation of minorities. It is no wonder that the Hungarians were the main obstacle to this plan. Sadly, after the first world war the conventional wisdom seemed to be that the Hungarian approach was the right one – and the legacy is still with us in places like Turkey, who adopted that approach as part of Ataturk’s modernisation.

Thanks for this. You may be interested in the work of Robert Musil (novelist). His magnum opus, “The Man without Qualities”, contains a lot about turn-of-the-century Austrian culture.