My reviews of the war in Ukraine are becoming less frequent. Thee war just goes on. At the start I spent quite a bit of energy thinking about how it might end. And yet the prospect of an ending is receding. We must resign ourselves to several more months of death and destruction, and probably many more after that. What will happen in that time?

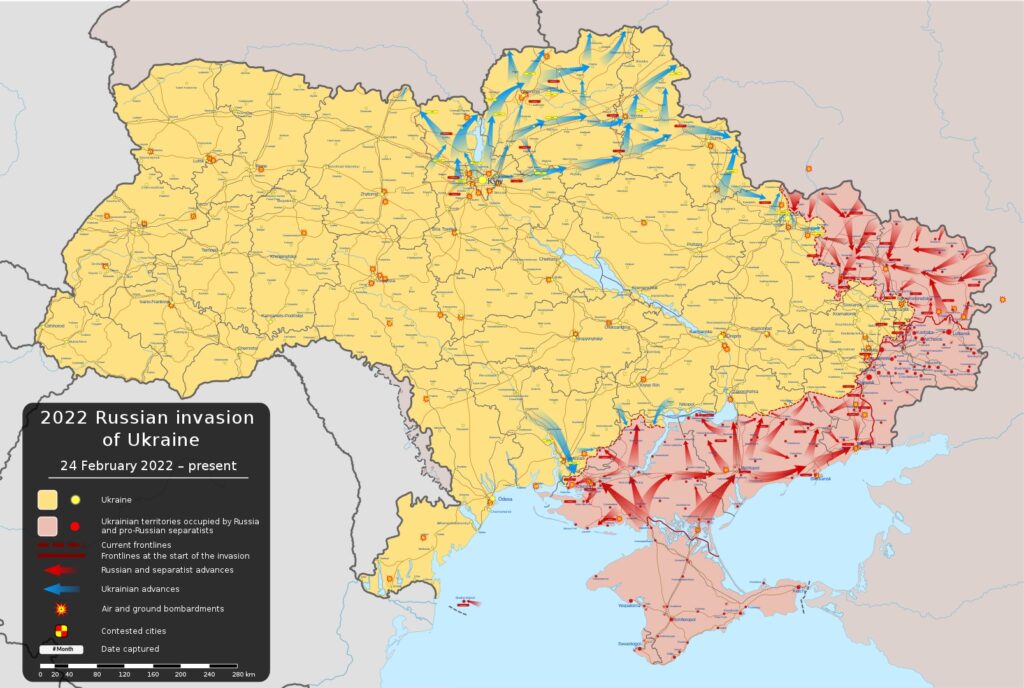

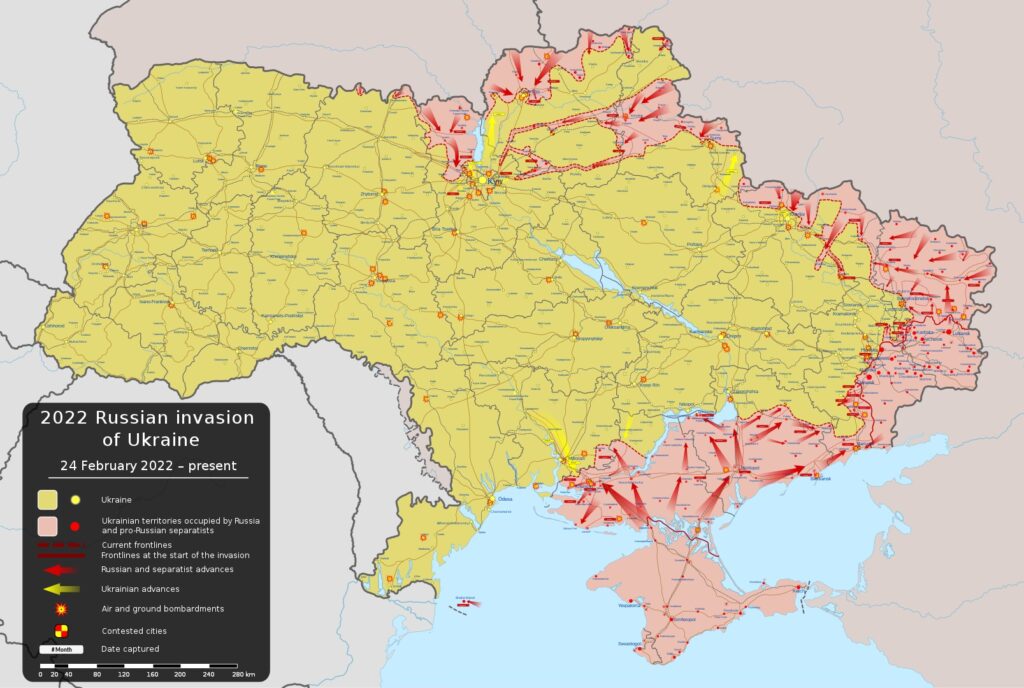

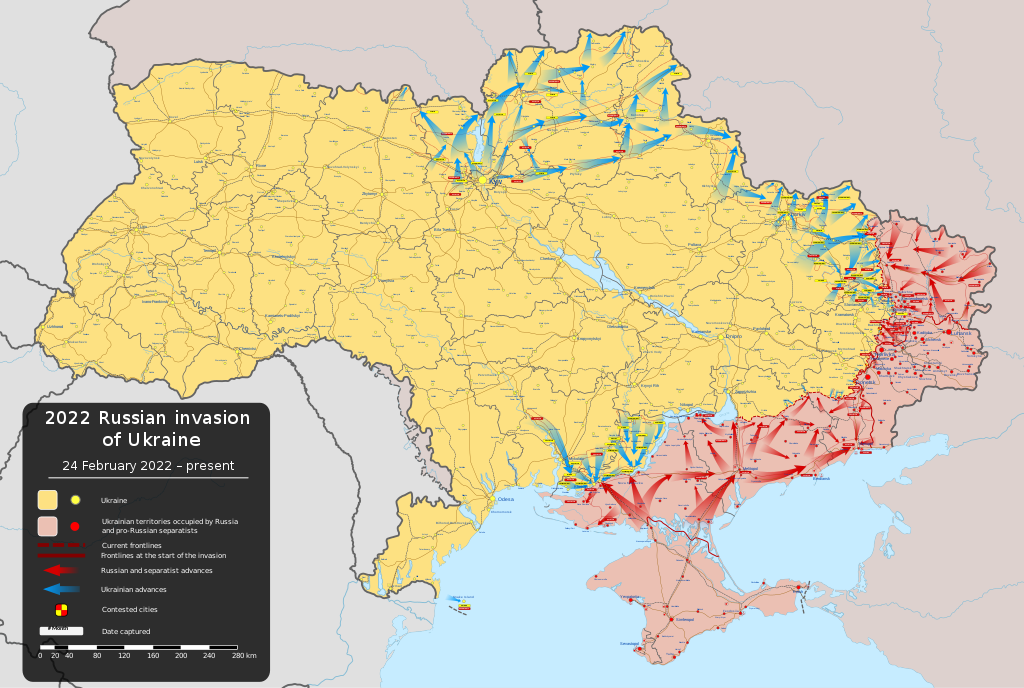

It is hard enough to tell what is happening now. Both sides are wary of releasing information, and it’s always for a purpose. The Institute for the Study of War (ISW), which is one of my main sources, now has extensive commentary on Russian attempts to manipulate what it calls “the information space”, both internally and in the wider world. Interesting as this may be, it reminds me of the story of the blind man looking for his keys under the street lamp: not because that is where he dropped them, but because that is where the light is. Beyond that there are formulaic reports of clashes along the three or four hotspots, which may be nothing more than aggressive patrolling, along with the endless artillery pounding. The Ukrainians are anxious to put out the story that the Russians are gearing up for a major offensive, using troops mobilised last autumn, along with, perhaps, a fresh mobilisation. The Russians seem to be dropping hints of this too, so it is probably true. Stories that Ukraine is preparing an offensive of its own come and go.

Much of the media kerfuffle in recent days has been over the supply of (relatively) advanced “main battle” tanks to Ukraine by its Western supporters. What to make of this? At the start of the war, Russia suffered desperate casualties amongst its armoured vehicles, and the idea that such things were obsolete in the age of drones and hand-portable antitank missiles Tok hold. After this came a gruelling war of artillery, and the usefulness such vehicles became more apparent. But their use seems to be a world away from the Second World War, which still shapes how many people view warfare. The Ukrainians clearly decided that they needed these tanks. Equally important, I suspect, are lighter “infantry fighting vehicles”, such as the US Bradley, which can transport troops – a cross between an tank and an armoured personnel carrier – a concept first developed by the Russians in the Cold War. These were promised to Ukraine by several countries (not including Britain, whose IFV is a bit of a failure) without much fuss before the tank row blew up. There is a lot more symbolism in the tanks, evidently. The whole episode was portrayed in the media as a show of disunity amongst the Western allies, and dithering by Germany. Well, there was certainly dithering – but such time the taken over important symbolic acts often makes them more solid. It is of the nature of alliances that they have arguments over strategy, as each participant has its own objectives. But often this helps improve the quality of decisions. It is possible to look on Germany as a foot-dragger – but it is the lynch pin of the alliance and has shown astonishing resolution, in spite of having much bigger problems thrown at it than the other allies.

Will these weapons transform Ukraine’s prospects, as the BBC seems to be reporting as fact? That is very hard to tell. A lot depends on logistics and finding the right tactics. The weapons were designed for a different type of war – but they are more capable than anything the Russians have. The Ukrainians have shown facility at both tactics and logistics, so we can expect them to make a difference. Still, transformative sounds too much.

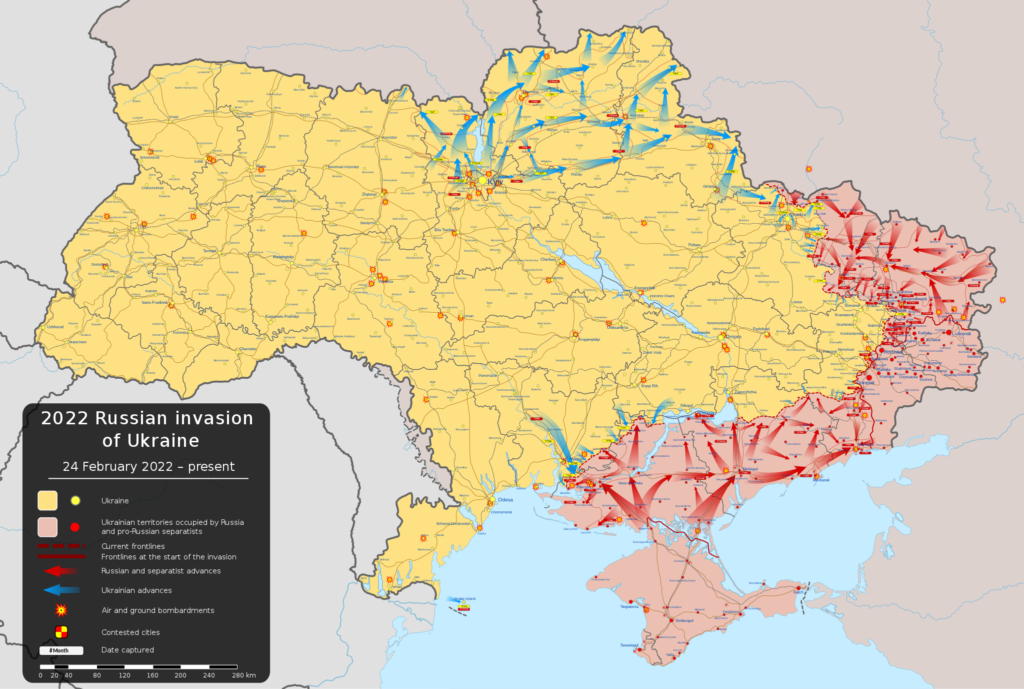

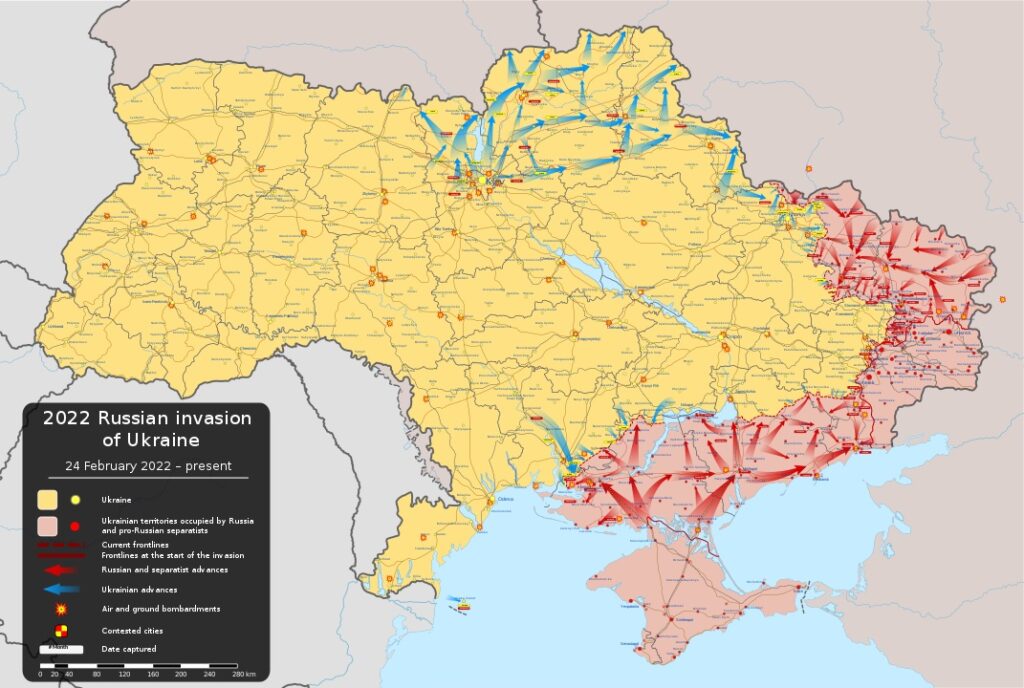

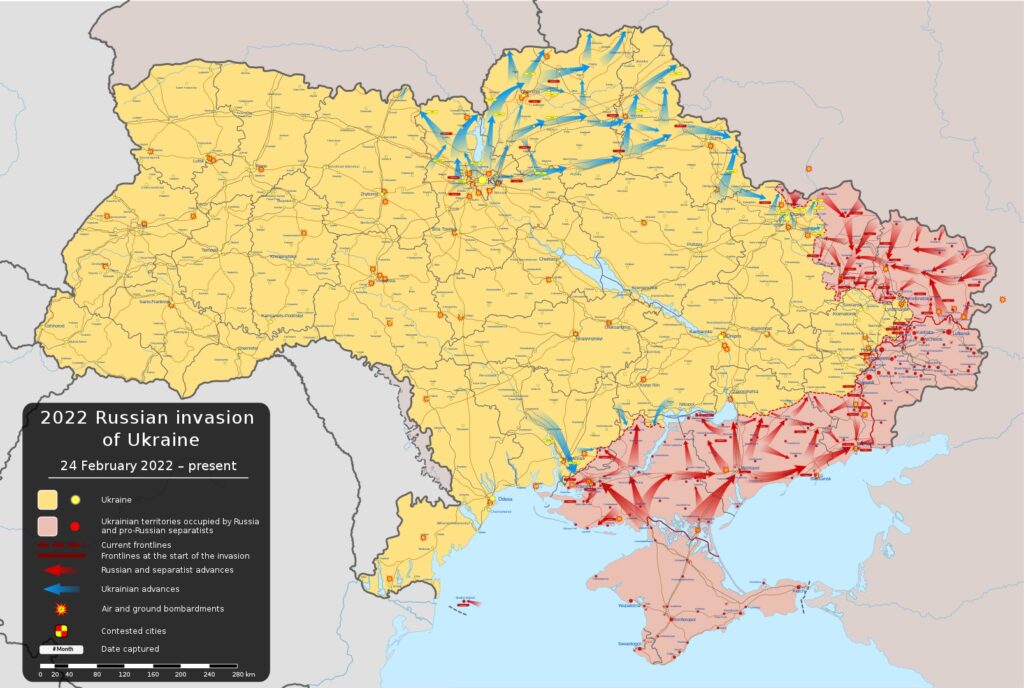

What of the coming Russian offensive? They have refreshed their manpower, and will be able to employ large numbers, by modern standards (but not by mid-20th century standards), at the pressure point. This is likely to be in the Donbas region, where the biggest political imperative lies, as well as the easiest logistics. The Russians have learnt a lot from their earlier mishaps, and have developed much more effective tactics. Still, they face three considerable obstacles. Firstly, the Ukrainian forces are much better prepared than they have been. We’ve heard a lot about how Russia has superior numbers, but this is misleading. Russia has huge manpower potential, but Ukraine can dig deeper on its resources, and has been doing so for the last year, building up and training large forces. Second, the supply of Russian munitions is not as plentiful as it was. The Ukrainians report that Russian artillery fire has slackened recently; doubtless this is because they are conserving stocks for the offensive – but it indicates that there are limits – and artillery is central to current Russian tactics. And third, Russia lacks experienced officers and cadres to lead its freshly mobilised forces. This is usually regarded as central to the effectiveness of any army. Still, the Russians have surely thought all this through, and there may be surprises.

And the Ukrainian offensive? If the new Western supplied armour is to be part of it, it does not look as if they will be able to pre-empt the Russian one. It will have to come later, assuming that the Ukrainians have the strength left. There is some rather wild talk of seeking to recapture Crimea (for example in The Economist). Militarily this is not quite as absurd as it sounds – if Ukraine can advance south of the Dnipro River, then that would put it in a position to isolate the peninsula. Politically, it sounds like a bad idea, though. Russian claims that Crimea is somehow more historically Russian than Ukrainian is their usual nonsense. But in 2014 it had a substantial population that looked to Russia, and many anti-Russian elements (such as the Tatars) have doubtless largely left. Ukraine would acquire a grumpy province that would be hard to secure, as well as delivering a massive humiliation to Russia.

But that opens up the question of how on earth this war is supposed end. It looks as if Russia will talk about it if the annexation of Ukrainian territory is on the agenda. That would obviously include keeping Crimea, but surely also large parts of the four oblasts that they formally annexed last September and now partially occupy. That is so far inconceivable to Ukraine – the war has cost them so much that they want more to show for it. We might objectively argue that such a deal would not be so bad – Ukraine has consolidated its moral hold on the rest of its territory, and its place in the “West”, including as this expression does such countries as Finland, Poland and Bulgaria – but this is far from the psyche of the men doing the fighting, and the citizens enduring Russian bombardment. What would be decisive is the withdrawal of American support from the country. If that comes it will be seen as a huge betrayal. We will certainly have to see how the bloody events of this spring and summer play out first. I don’t think Joe Biden’s hopes of being re-elected as president in 2024 would survive such a retreat.

Could Russia’s resolve weaken? There have been plenty of examples of despots hanging on for years while their countries go to the dogs (look at Syria or Venezuela). Russia has already endured massive losses. A big test will be if the regime goes for a further wave of mobilisation, of which there is already much talk. Last autumn’s wave was clearly politically costly. Meanwhile the economy weakens, as war priorities take over, and many men are conscripted or have fled the country to avoid that fate. But economic hardship will not weaken its leader, Vladimir Putin, who sees his mission in terms of historic destiny, and who has so much personally tied up in the war. His war has failed its original objectives, but he cannot afford to admit defeat. Perhaps a coup will carry him away. But this would be done by Kremlin insiders, who are also committed to the war – there would be limits as to how much such people could concede. Mass unrest that would cause the collapse of Russia’s internal security apparatus looks vanishingly unlikely – though it is conceivable that another wave of mobilisation could provoke it.

The outlook is very gloomy indeed. The war presents as clearly as ever the main lesson of war: never start one. But there was plenty of evidence for that before this misadventure began.