After a bit of introspection on the sorry state of Britain’s Liberal Democrats, I am moving on to consider the not quite so sorry state of the Labour Party. The party was all but wiped out by the SNP in Scotland, experiencing some of the most spectacular swings ever seen in British politics. In England and Wales the party completed the Conservative demolition of the Lib Dems, picked up George Galloway’s Respect seat, but made little headway against the Conservatives, even losing some seats. And that from a historic low point in 2010. It was its worst result in seats in the post war era. What to make of this?

This bad result has led to not a few doom-laden pronouncements from party insiders and columnists, about how the party could be out of power forever unless it sorts itself out. My first reaction is to remember the quote from Macbeth: “It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”. I remember similar pronouncements after the 1992 election… before a turn of events that led to Labour’s biggest ever victory in 1997. The Conservative majority is narrow, and that party is riven by its own divisions, notably over Europe. In England Labour has convincingly seen off its main rival, the Lib Dems. Another rival, the Greens, and Plaid Cymru, its main rival in Wales, failed to advance. Ukip, its last important rival, looks in complete disarray.

But it won’t do just to blame Labour’s defeat on tactical mistakes by its leader Ed Miliband, who resigned after the result. It was clear enough what direction Mr Miliband was going to take when he stood for the leadership in 2010, and overall he delivered it with a great deal of competence. Most Labour insiders were, as Mr Miliband memorably said of the Lib Dem association with Tory policies in coalition, complicit. He, and most of the party, wanted Labour to bounce back quickly, with a smart step towards its roots on the political left, but without having any major internal political bust ups on policy. They were relying on the coalition parties to lose the election, rather than get onto the front foot themselves. We must remember that in those early coalition years, with the scale of government cuts becoming evident, that there was outrage. Those on the left saw what was happening as an evil attack by the privileged Tories on wider society. Those of a more centrist viewpoint were persuaded by Keynesian economists that the government was making a catastrophic error. The two factions could unite in their condemnation of the government without having to agree on the optimal size of the state, or how to lift economic productivity.

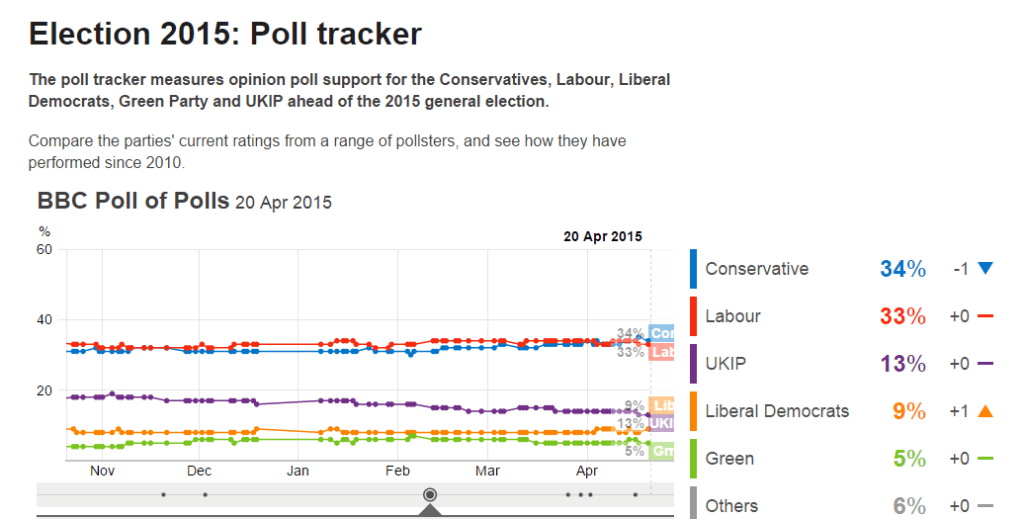

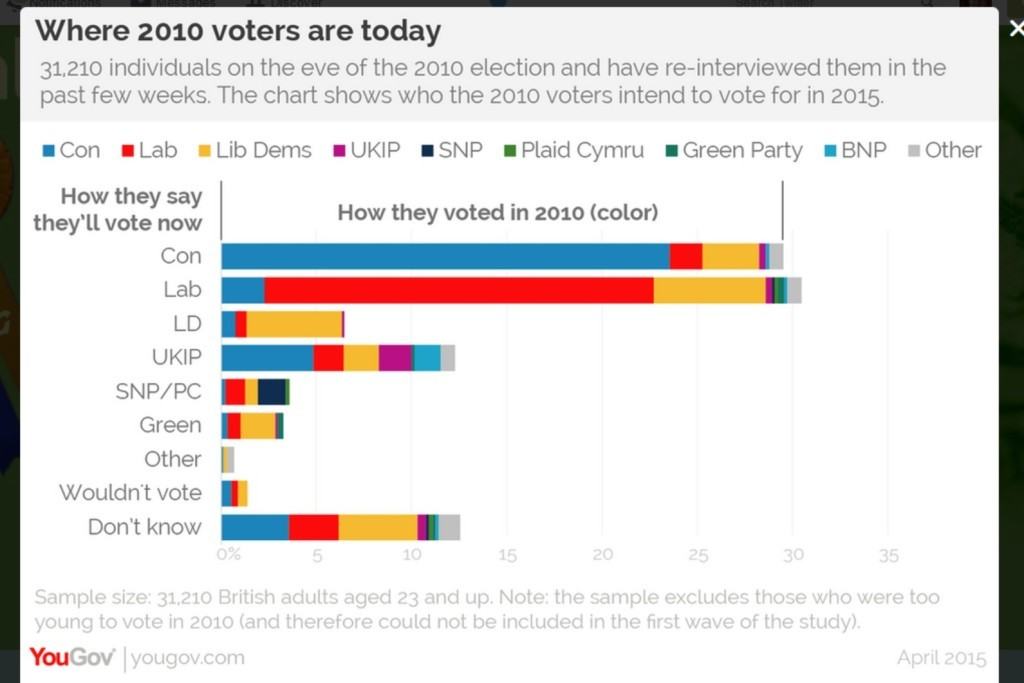

By the time it was clear that the economy was not going to take a downward spiral, whether through the government’s sound judgement or through sheer good luck, it was too late to have these searching conversations. Labour’s criticisms of the government’s economic record resonated with the public, but the party was unclear on how it was going to do any better. It developed a few eye-catching policies, on energy prices and the minimum wage for example, which were individually popular, but did not add up to an economic strategy. This left the party with little traction against the Conservatives, even as it was clearly scoring against the Lib Dems. They seemed to think that would be enough, with what was dubbed the “35% strategy”. It turned out this was not enough – they hadn’t reckoned on a number of things: that the Tory squeeze on the Lib Dems would be just as effective as their own, and that there would be significant leakage to the Greens and Ukip.

But the real disaster, that most Labour insiders had not foreseen, was the meltdown in Scotland – even after the SNP’s sweeping victory in the 2011 Scottish elections. This seems a wilful failure to face up to realities that were too awful to contemplate. Labour’s political representation is based on a bedrock of support in the old industrial centres where the party is virtually unchallenged, especially in opposition. Scotland was a large part of this. There was (and is) a sort of grand bargain. These areas provide safe seats for Labour’s Westminster elite, allowing them to concentrate on their careers in the capital without connecting much with local voters; meanwhile local party bosses had a pretty free hand to run their fiefdoms using the good old-fashioned politics of patronage and menace. Local voters were unhappy with this, but where else could they go? In Scotland the SNP patiently built up a position as a clear alternative – and then pushed the whole rotten structure down. Labour’s crass handling of the referendum on Scottish independence did not help their cause, but the roots of their problem lie in generations-old institutional failure.

And those failed party institutions live on in Labour’s heartlands in England and Wales. They are vulnerable to a similar collapse – though its source is unclear. Ukip now seem to be a clear challenger – but they will need more organisational nous to develop that threat. Some Conservatives aspire to mount a challenge, but they have a lot of class baggage to overcome. The Greens are middle-class lefts who fume at abstract nouns (“austerity”, “the Market”, and so on), and not the sort of gritty campaigners needed for this sort of work. The Lib Dems blew their credibility with the coalition and it will take a long time to rebuild it, if they ever can. So matters look safe for now – but the party should beware of taking its regional base for granted.

So the party has a difficult manoeuvre to undertake. It must become more Tory to win back voters from that party. It must rebuild in Scotland, providing a compelling critique of the SNP’s record in Scottish government. And yet it must reassure its core voters.

Just how it is going to do all of these things is unclear, but the task is not impossible. I believe that the key is for the party is to embrace devolution of power to regions and districts. This solves a number of problems at once:

- It provides a long-term framework for Scotland’s role in the UK

- It delivers something to Labour’s neglected heartlands away from the capital.

- It is also one of the more promising directions to revive the country’s lacklustre economy.

Alas such devolution runs counter to the party’s instincts. Its reaction to the coalition’s devolution deal for the NHS to Greater Manchester was revealing. Andy Burnham, its then health spokesman and now a front-runner in the leadership stakes, trotted out all the old tropes against devolution, and damned the concept with faint praise. Still, Mr Burnham has proved flexible in his beliefs before now, and he may yet get it.

The party’s priority for now, though, is to pick a leader capable of leading the party through this minefield. As the FT’s Janan Ganesh points out, this isn’t a matter of providing a clear vision. It is a matter of solid political judgement, and the strength to weather internal controversy. The jury is still out on the various contenders, and I wouldn’t write any of them off for now.