Yesterday I went to the launch of the Liberal Democrat 2015 Manifesto,  which sets out the party’s policies for the forthcoming British General Election. It is not a ringing declaration of liberal values designed to strike fear into the party’s opponents. It is a triumph of practical politics.

which sets out the party’s policies for the forthcoming British General Election. It is not a ringing declaration of liberal values designed to strike fear into the party’s opponents. It is a triumph of practical politics.

The first thing to notice is that it is quite small – A5 format rather than the showy A4 of former versions. But that is not because it lacks content. It has 151 pages plus an index, and these are typically densely written in a small script. Almost nobody is going to read the whole thing. I have only picked at it. In the past I have slipped a copy of the manifesto through voters’ letterboxes after a request. This time I will just offer the link (above, incidentally).

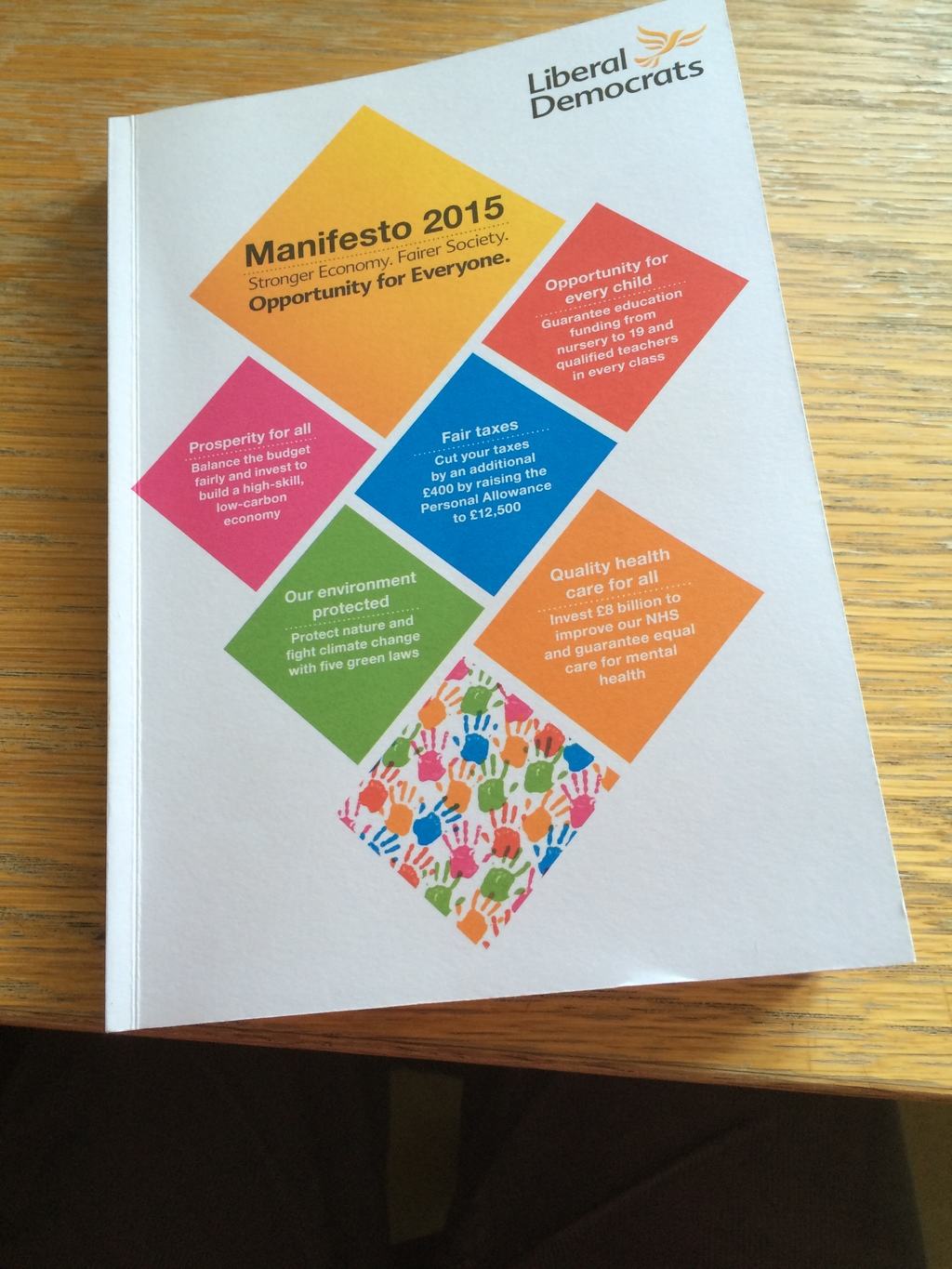

The document succeeds in following the election strapline of “Stonger Economy, Fairer Society, Opportunity for All”. Five key pledges grace its front cover:

- Balance the budget fairly and invest to build a high-skill, low-carbon economy

- Guarantee education funding from nursery to 19 and qualified teachers in every class

- Cut taxes by an additional £400 by raising the Personal Allowance to £12,500

- Protect nature and fight climate change with five green laws (specified elsewhere)

- Invest £8 billion to improve our NHS and guarantee equal care for mental health

Beyond this there are eleven chapters, chock-full of policy proposals. These comprise a lot of sensible ideas, some interesting ones, some gimmicks. Plenty of these originate from the two policy groups that I have been a part of (Quality of Life and Sustainable Growth). One may be said to have my fingerprints on it – putting Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) into a slimmed down core national curriculum. There are some disappointing gaps. In the education section, for example, I can’t find any reference to changing the measurement of school performance by the progress that all children make – as opposed to the number that pass a particular threshold. This has been promoted by Lib Dems in government, and could dramatically improve the way many schools are run. Also a defence might have been made of the government’s health reforms – moving to a doctor-led system with proper local accountability, in place of the pantomime accountability of the Secretary of State. But these are details in a document that few will read in full.

The first impression is overwhelming and underwhelming both at once. Overwhelming in its volume. Underwhelming in its lack of stirring themes -the party’s strapline is hardly going to put fire in the belly after all – all parties will say they are doing it. But on reflection I think it is rather wonderful. The party has learned much from its spell in government.

The first point is that political progress rarely results from revolutions. The Greens call for a peaceful revolution, turning the whole way British government works upside down. In the past, I have wanted to do the same. Tear the whole system down and start again. Of course, revolutionary change has its place. Forming the NHS in the 1940s was a bit of a revolution, for example. But mostly revolutions bog down or get diverted by power struggles. The wonder of human life evolved through a process of incremental evolution (or so I believe); that makes it a bit illogical and random, but the advance from single-cell organism remains astonishing. So it must be in politics.

And the second point follows swiftly behind this. The Lib Dems are not a majority party, and probably never will be. We will never have a mandate to implement our vision in one bold step. (And neither will the Greens, which renders their policy platform pointless and laughable). We make change by persuading other people that our policies are the best ones, one at a time.

And the people we must persuade are people who belong to other parties. The voters are not interested in the ins and outs of individual policies; they delegate that to politicians. Our policies get implemented in three ways: other parties may adopt them as their own (“stealing” it is sometimes called by insiders); or they may be forced to implement them as part of a deal to pass parliamentary legislation; or the party can implement the policies directly through a coalition government. The last is the most powerful, as those doing the implementation have the true vision.

The Manifesto is designed to be basis for the Lib Dem share of any coalition government. None of the polices are so radical that no other party will ever agree to implement them – least of all the five headline pledges. The last manifesto lacked the requisite detail. Taken together the policies would up to an important liberal shift in the way the country is governed.

There’s something else. The manifesto proposals are clearly drawn from the party’s deliberative policy making processes, to which many members have contributed, and on which many more have voted at party conferences. These aren’t the bright ideas of a select elite dropped from a great height, or crafted by campaign “strategists” based on focus groups (or not most of them anyway). This ensures a basic level of thinking through – compare that the Conservatives’ muddled policies on the right to buy housing association properties, which starred in their own manifesto. It also gives some point to joining the party as a member, rather than just being used as a footsoldier in somebody else’s career.

Of course we need to do the inspiring vision thing too. We need to recruit new people to be the party’s core supporters and activists, and keep those we have in fighting spirit. But that’s a different time and a different place.

But what’s on display here is liberalism’s secret weapon. It may only be a minority creed, but its cosmopolitanism gives it a hearing in many audiences. People may not make a liberal society as their first choice, but as a second choice it has a very wide appeal. That’s a basis on which you can negotiate. And liberals are often ahead of the trend too; their ideas become common wisdom in time. Our country is a much more liberal place than 50 years ago. It really is possible to reach a liberal future one policy at a time.