I will break my self-imposed silence because yesterday’s British Budget is one of those great set-piece occasions which can be used as a moment of reflection. Predictably, most in the news media squander this in a silly game of speculation about the short-term prospects of political leaders. But the Budget poses more profound questions.

The government faces two profound economic problems, which it must either learn to live with or expend political capital to solve. These are low productivity and housing. There are other big problems, of course: Brexit, austerity, regional disparities and income inequalities, for example. But Brexit is more about means than ends; austerity is symptom of the productivity problem; and the other problems are not so high on political agenda right now, though they are important to both housing and productivity. Broadly speaking, the government is being forced to embrace the productivity problem, and is doing its best to confront aspects of the housing problem, without being able to do enough.

Let’s look at productivity first. This is about production and income per hour worked. Since unemployment is now low, and immigration is looking less attractive, increasing productivity is the key to raising incomes, and, above that in my view, to raising taxes. Weak tax revenues lie behind austerity – the cutting of public spending to levels which are now unsustainably low. The government is forced each year to spend extra money to fix some crisis or other brought about by austerity. This time it was Universal Credit and the NHS. Next year it will be police and prisons, after that it will be schools and student loans. And so it goes on – this is no way to build for the future. The government could try to raise taxes, but this is so politically unpopular that not even the Labour Party is talking about it – they persist in thinking that there is easy money to be raised from big business, rich people and confronting tax evasion. So growth it must be, and productivity must rise. But productivity is stuck in a rut. The big news for this Budget is that at long last the Office for Budget Responsibility has given up hoping that there will be a bounce back, and so reduced its forecasts of income growth, which are used to set tax and borrowing assumptions. The Chancellor, Philip Hammond, talked about fixing this, as all politicians do, but in practice has done very little about it. Labour, for all their huffing and puffing, are no better. Both parties propose a number of sensible small things, like increasing public investment and education, but nothing that gets to the heart of the issue.

So the political class have chosen to embrace slow productivity, by their actions if not their words. They are right, though they need to think through the consequences. My take on the productivity puzzle is different from pretty much everybody else I have read. I think that the primary cause is what economists call the Baumol Effect. The problem is not the failure of British businesses to embrace improvements, but the limited demand for goods and services that are susceptible to advances in productivity, such as manufacturing. There are things that can be done to raise such demand, but these mainly have to do with increasing incomes for those on low incomes – people with high incomes consume less as a proportion of income, and spend more on low-productivity items that confer status. Also if demand for exports could be raised, and imports diminished, that would help – international trade is mainly about high productivity goods. But nobody really has much idea how to deal with these problems beyond tinkering at the edges with minimum wage adjustments and such.

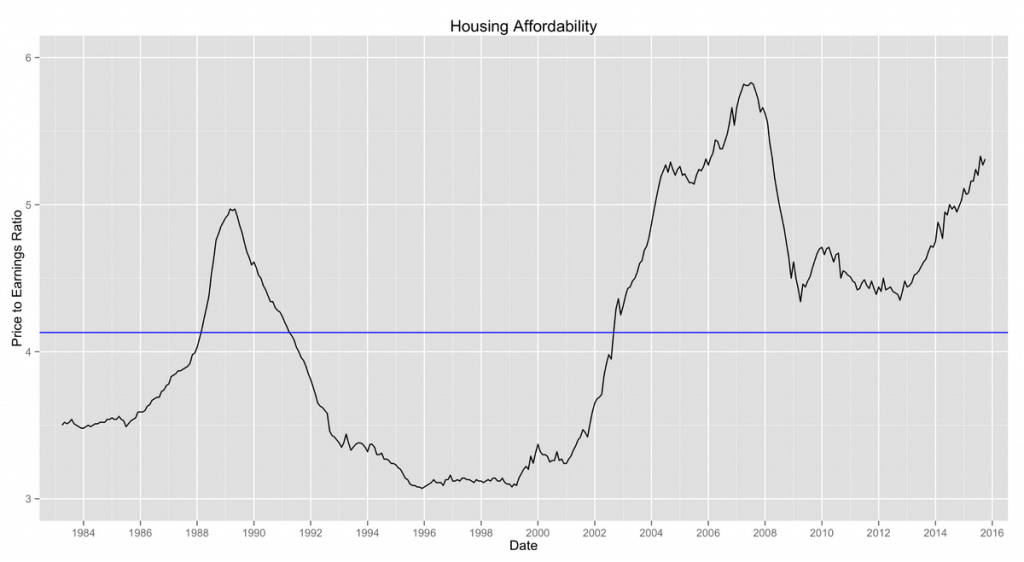

So what of housing? What, exactly, is this about? It is about high costs to both buy housing and to rent it. This is a very complex problem with deep roots. Most analysis is superficial, but this article in the FT by Jonathan Eley is a good one. Among a number of interesting points he makes is that the low number of new housing units being built in recent decades compared to earlier ones is a bit misleading. In those earlier decades a lot of housing was being destroyed: slums and temporary housing for victims of bombing in the war. It is not necessarily true to suggest that the problem is that too few houses are being built. In fact there are deep structural problems with the housing market. One is that private borrowing has been made too easy; another is that changes to housing benefit has subsidised demand for private rental accommodation. The result of this and a number of other things has forced up the price of land relative to the housing built on it, and made trading in land central to economics of private sector developers.

The upshot of this is that it is hard to see any solution to the housing problem without a substantial intervention by the state to directly commission house building, and social housing in particular. Another issue is building on greenbelt land outside cities, which is now forcing suburbs to turn business premises into housing, and turning suburbs into an unhealthy housing monoculture. Caution on greenbelt building is warranted, of course, as suburban sprawl, as demonstrated in so many countries in the world, is not desirable either. Mr Hammond did practically nothing on either of these critical issues. He did try to tackle the housing problem, but mainly through the private sector and private markets which are structurally incapable of making things better for the growing proportion of the population weighed down by excessive housing costs.

That is entirely unsurprising. Solving the crisis, especially in an environment of low economic growth, means that current levels of house prices and rents have to fall. That is a direct attack on the sense of wellbeing of the Conservatives’ core constituency: older and better off voters. And if that isn’t enough, property developers and others with a vested interest in the current system are showering the Conservatives with money. A politically weak government is no shape to take this on.

And that, I think, is the most important political fact in modern Britain. Housing costs are not an intractable problem that we must learn to live with, like productivity. One day it will solve itself in an immense period of pain as land prices, and much of the financial system, collapses. The sooner it is tackled the less the pain will be. Labour may be useless on productivity, but they are much stronger on housing. They have a much better prospect of doing something useful. That does not mean they will win the next election – the forces of darkness on the right should not be underestimated. But it does mean that Labour is looking to be the lesser of two evils.

For my party, the Lib Dems, this is important. It means its stance of equidistance between Labour and the Tories needs to be modified. The turning point, in hindsight, should have been that moment in coalition with the Tories when the then Chancellor George Osborne said that he could not support the building of more council houses because that meant more Labour voters. The coalition should have been ended then and there. Just as in the 1990s when the Lib Dems leaned towards Labour, the party needs to accomplish the same feat now. It is much harder because Labour has abandoned the centre ground. But that is where the country is at.