Such is the paradox of the information age. Massive amounts of information from across the globe is at our fingertips, and we can now use AI tools to retrieve it with startling efficiency. But news reporting, especially local news reporting, has collapsed – so many, many interesting things are liable to escape our attention because they will never get into to the accessible database. There has been a wealth of reporting on last week’s local election results in England. But many interesting, and important, local stories remain unremarked. Such is the case in my local area, with the district council elections of Wealden in East Sussex – and arbitrary bureaucratic agglomeration of villages and small towns, whose main centres are Uckfield, Hailsham and Crowborough, each of roughly equal size.

The first point to make about this is that I wasn’t involved in these elections, in spite of being a party member. I haven’t talked to any of the actors since long before the campaign started. My reporting is based simply on the results published by the council. I hope to find out more later – but I’m not minded to harass exhausted newly-elected councillors who have important decisions to make about running the council. I’m a blogger, not a journalist.

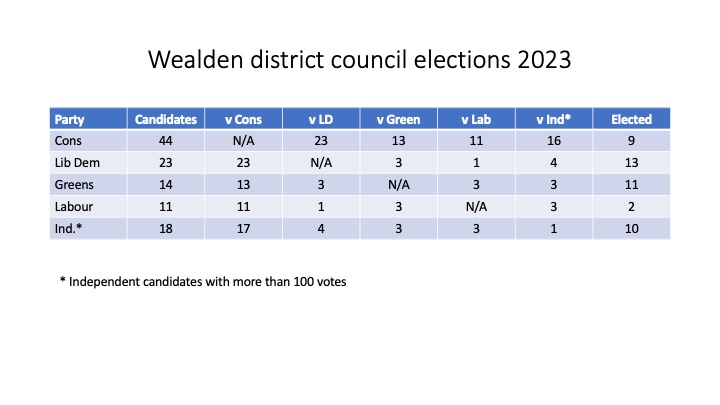

It was the first British public election since 1979 in which I did not vote for the Liberal Democrats, or one its predecessor parties. That was because they did not field a candidate in my ward. There were only three candidates: a Conservative, a Green and an independent who did not put up much of a visible campaign. I voted for the Green candidate, Christina Coleman, who won with 64% of the vote against the Conservative incumbent councillor, Roy Galley, who had won in 2019 with 59% of the vote, against just a Green candidate. Ms Coleman increased the Green vote from 523 to 1,107, while Mr Galley’s vote sunk to 545 from 749. As I searched through the results, I found that this outcome was not untypical. The Conservatives contested wards opposed by typically only one other party. And they lost badly, sinking from 34 councillors (out of 45) to just 9, behind both the Lib Dems (13) and Greens (11). This was a shocking result in a part of the Blue Wall that is so blue that most people don’t regard it as politically competitive. This bespeaks serious trouble for the Conservatives. It is hard to exaggerate the degree of disgust with the party amongst most of my neighbours, whom I would describe mostly liberal conservatives. One Conservative inclined neighbour is even more unforgiving of the Liz Truss episode than I am.

But that is unremarkable. It has been picked up by the main media commentary. What is remarkable was the degree of cooperation amongst the Conservatives’ opponents, and how well this worked. To put a bit of substance behind this story I have analysed the detailed results in the table above. This is all my own work and it’s possible the odd error has crept in. First, some basics to help understand the figures. There are 41 wards, four of which elected two councillors, and the rest just one. One was uncontested – the Conservatives were elected unopposed. The Conservatives contested all the wards except one (where an independent stood, and lost, against a Green). In the analysis I have tried to exclude candidates without serious backing or a campaign. I judged these to be independents who did not manage to gain 100 votes, and minor parties (though in one ward there was a Reform UK candidate, and in a another a pair of Ukippers, all of whom received over 100 votes); I have left in all of the Labour candidates, although one failed to reach 100.

The Lib Dems put up 23 candidates, doubtless so that they could claim that they could theoretically win a majority on their own. But they were opposed by the Greens in only three cases, and Labour in one, with “serious” independents in four. Eleven of the Lib Dem candidates faced no other serious opponent than the Conservatives; they were all elected – but only two others were. The Greens put up only 14 candidates – nine of these faced only one serious opponent (well, 10 if you exclude a weakly supported Labour candidate) – all (ten) of these were elected, along with one other. Three Labour candidates out of 11 were given a clear run against Conservative candidates; none were elected. Two Labour candidates were elected in three-cornered battles with Conservatives and independents (including a split result in a two member ward) – their first councillors in the district. The independents are by their nature not a coherent party, so the analysis means less – but their 18 serious candidates were involved in only four straight fights – three against the Conservatives (which they all won) and the lost fight with a Green. There were 13 three or four cornered contests: the Conservatives won six of their councillors here. These six, the two straight fights with Labour and the one uncontested ward were all the councillors they won. They won no contest in a straight fight with Lib Dems, Green or Independents. In two case of the more complex contests, the Conservatives prevailed with under 40% of the vote. In only three cases Greens and Lib Dems ran candidates against each other – the Conservatives won in two of them (with under half the vote), with the Greens winning the third comfortably with the worst Lib Dem performance of the day.

So far as I know there were no formal pacts – if there had been, the picture would have been a bit tidier. But cooperation is evident, and, as a device for winning against Conservatives, it proved highly effective – but less effective where Labour were putting up the candidate. How far can we extend the conclusions to a general election? Local and national elections are different – but the main problem for the Tories in Wealden was their unpopularity at national level. Their Wealden administration is not particularly unpopular, though no especially popular either. This suggests to me that an electoral pact between the Greens and the Lib Dems could turn some seats in the Blue Wall unless the government can seriously scare voters about the prospect of a Labour-led government. Wealden borough closely corresponds to a parliamentary seat, also called Wealden, which is very safely for the Conservatives (the Lib Dems edging ahead of Labour into a distant second) – but this all changes when new parliamentary boundaries come in. Such a pact would follow one made in 2019, but could be much more effective if voters are less scared of Sir Keir Starmer as Labour leader than Jeremy Corbyn.

But it would be very hard to bring Labour into such a pact. Many former Conservative voters will vote for the Lib Dems or Greens (somewhat ironically since the Greens are closer to Corbyn’s Labour than Starmer’s), but draw the line at voting Labour. So there is much less in such a deal for Labour than the other parties, and it would be a major distraction from Labour’s main campaigning focus. Also Sir Keir is setting his face against electoral reform (which would be another distraction for him), which reduces the attraction of Labour to Lib Dems and Greens.

In the right circumstances electoral pacts work. Given the severe distortions imposed by the current electoral system I would have no qualms about my party entering into such a pact.