This weekend the Liberal Democrats meet for their Spring Conference. To most observers of the political scene, this is an irrelevance. But with the growing gap between Labour members and the general voting public, and the Conservative Party riven by splits on Europe, who knows what opportunities might arrise for the party? I still care about it, anyway.

The party is rebuilding itself after the five year car crash of coalition government ended last year with it being reduced to near irrelevance in the House of Commons. And that followed five years of rather gentler decline after its peak year of 2005. The party conferences are an opportunity for members and leaders to decide what the revitalised party stands for.

One complaint after last year’s meltdown was that the party was weak on economic policy, and so let others set the agenda. No doubt that motivated the submission of a motion on the economy as the first item of policy business on Saturday with just an hour’s debate. Alas the motion plumbs the depths of awfulness.

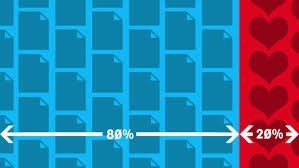

I can’t find a neat link to it, so I will reproduce it here in full below, so you can judge for yourself. But with its 10 whinges about the current situation, and 15 proposals, I’m not sure I would recommend a close read. It is mostly unobjectionable. It has some worthy ideas, and some airy aspirations. Item 11 od the 15 reads: “Addressing inequality through a renewed commitment across Government and society to analyse and address Beveridge’s Five Giants in modern society.”

In some contexts a list of 15 rather disconnected policy ideas is not a bad idea for a policy motion – for example if the party was planning to negotiate a coalition programme from a position of strength. This is hardly the context now, and even then it fails. Just what would you do with a commitment to tackle the Five Giants in a coalition negotiation? Instead all such a long list of vague ideas serves is to offend people whose own hobby horses are left out of the 15, or are underrepresented, or given too low a prominence.

What the party actually needs from a debate on economics at this stage in the political cycle either of two things.

The first thing it could do is set out a very limited number of general themes, around which to hang more detailed policies. These need to display a bit of vision, and show what the party is all about. I suggested a few last year: green growth, small is beautiful (or greater diversity and innovation, if you will), problem-solving public services and addressing inequalities and imbalances. It would not be hard to do better than that, and any debate would say something about the party’s values and campaigning priorities. I can find no such clear general themes in the motion. Worse, I am rather shocked to see so few references to environmental sustainability in a party that used to pride itself on environmental consciousness – that alone is reason enough to vote the motion down.

The second thing it could do is develop a particular economic idea or solution to a specific economic problem. There are plenty of places where this needs to be done: investing for green growth; tackling the housing crisis; free but fair trade; taxing businesses. Or the role of fiscal policy in economic management, though the chances of getting a rational debate on that area in a left of centre political party are slim. This is actually where the heavy lifting needs to be done, and where the Lib Dems can make a substantive contribution to the wider political debate on economics. The real world of democratic politics is evolutionary; revolutions fail. What is needed is a series of practical changes, each of which will works on its own merits, and which collectively will amount to radical change. The motion does point to some specifics, but each of its 15 proposals needs to be picked apart in a debate of its own. Instead we have a series of vague and useless commitments.

And as a result the motion is a complete waste of time. Much hope seems to be being placed on amendments. But unless these are allowed to replace the motion with an entirely new one, which would be an abuse of process, I can’t see how it can either be turned into a general vision or a specific economic proposal. It is neither fish nor fowl. The best thing to do with it is to throw it out and start again.

Conference re-asserts the Liberal Democrats’ continuing commitment to sound public finances, social justice, an open economy in an open society, and the principle of free markets whenever possible with intervention where necessary by an enabling state.

Conference notes:

a) The Liberal Democrats’ effective record in Government in stabilising the public finances and major contributions in the fields of apprenticeships, banking regulation, the British Business Bank, the Green Investment Bank and the promotion of innovation through the Catapult network.

b) The fragile nature of economic recovery following the 2008 crash, evidenced by interest rates which are historically low and continued Eurozone uncertainty.

c) The growth of house prices carrying the threat of a price bubble and subsequent crash.

d) The Chancellor’s unhelpful and arbitrary re-definition of the deficit, doubling the total by including capital spending, in his attempt to justify Tory spending cuts.

e) The medium-term risk to the UK economy posed by increasing and unsustainable private and household debt.

f) The threats to the UK economic prospects posed by Conservative approaches to UK membership of the European Union and immigration.

g) The International Monetary Fund’s advice to reduce debt through growth not cuts.

h) The UK economy’s over-dependence on London and the South-East.

i) The UK’s bad record in allowing the growth of an increasing number of young people with low levels of education, training and aspiration.

j) Growing inequalities in wealth and income, coupled with unfair and regressive action against the poorest people in the country, now exacerbated by the assault on welfare spending.

Conference calls for effective measures to support and grow the UK economy, including by many established Liberal Democrat policies:

1. Increased investment, both directly by Government financed by public borrowing, and stimulated by Government, particularly in affordable housing including social housing and infrastructure to support balanced growth throughout the UK.

2. Support for planning reform, institutional lending to small builders and action by local authorities for planned development, including assembling land for auction.

3. Further measures to improve and regulate banking services by promoting efficient lending, particularly to small and medium-sized enterprises, encouragement of challenger banks and increased personal accountability.

4. Strengthening takeover legislation to protect the country’s science base.

5. Reversing cuts in the development of green energy and promoting investment in green business initiatives.

6. Further development of the Government’s industrial strategy, promoting co-operation and supply chain development in key sectors for the long-term.

7. Re-balancing the economy towards manufacturing industry and regions, based on the coherent and substantial devolution of political and financial power.

8. Further reform of corporate governance to encourage ‘long-termism’ and to discipline executive pay, including an employee role in determining executive pay.

9. Renewed emphasis on vocational education and training, particularly through effective apprenticeships and especially higher-degree level and engineering and construction apprenticeships.

10. Coherent efforts across Government Departments to address the needs of young people who are excluded from the labour market and participation in wider society.

11. Addressing inequality through a renewed commitment across Government and society to analyse and address Beveridge’s Five Giants in modern society.

12. Investigating sustainable ways of funding universal services, including a cross-party, cross-society settlement on funding health and social care.

13. A new commitment to taxing unearned wealth, including Land Value Taxation.

14. Measures to dampen the growth of asset bubbles in opposition to Conservative approaches which tend to increase that growth.

15. Support for more diverse ownership models including worker ownership, social enterprise, mutuality and co-operation.