If there is something that unites British Labour Party people, from rightist Blairites, to Brownites, through to the leftist Corbynistas, it is that the Labour government of 1997 to 2010 should not be held responsible for the financial crash of 2008/09, and the terrible state of government finances that followed. They are made indignant by Conservatives (and Liberal Democrats) who go on about how Labour is to blame for the financial mess the government left the country in in 2010, when the budget deficit had ballooned to over 10% of GDP. But the public finds the Tory line more convincing. And if Labour are to throw off this albatross, it will have to move on from its air of injured innocence.

There are two dimensions to this question. The first is a question of fact, or purports to be: how much responsibility did the Labour government actually have for what went wrong in the economy? The second is what is going on in people’s heads when they think of Labour and the economy, and how the party might address it.

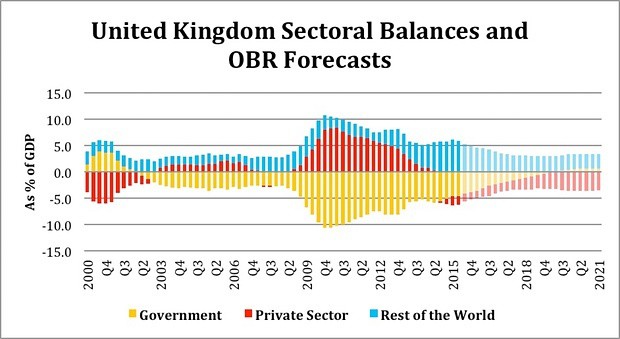

On the first question, Labour have quite a few sympathisers outside the party. And certainly the direct line of attack made by Tories is not all it seems. The Tory narrative is that Labour went on a spending splurge in the boom years, which then proved completely unsustainable, leaving their successors choice but to implement austerity policies. Defenders of Labour’s record point out that there was no big government deficit before the crash. It was a relatively modest 2.5% or so in 2006 and 2007, and not regarded as irresponsible at the time. Nobody foresaw the financial turmoil, which originated in American sub-prime mortgage markets.

The Labour defence against this charge is mostly true. But not quite. Gordon Brown, as Chancellor (he became Prime Minister in 2008), claimed to operate government expenditure on a “golden rule” which meant no net borrowing over the economic cycle. But he had taken to moving the goalposts rather than applying the rule strictly. Had he followed his own rules as originally intended, there may not have been a deficit as the economy turned in 2007. But that only accounts for 2% of the problem. There was another 5% that came from somewhere else, allowing for a normal cyclical swing of 3%, and which cannot be blamed on Labour profligacy.

If you take a wider view, however, Labour’s defence becomes more difficult. British government finances were worse affected than other major industrial countries, from France to the USA, and much worse than some, like Canada. There are broadly two reasons for this. The first is that Britain had a bigger financial crisis, because it had a bigger banking sector, especially in international banking, and so was more affected by its collapse. The second is that tax revenues fell unusually sharply in Britain. Both aspects have government fingerprints on them.

Take banking. Labour lauded the rise of the international banks, and celebrated Britain’s “light-touch” regulation that helped bring this about. They gave RBS’s Fred Goodwin a knighthood for no other reason than that he had expanded his bank, recklessly as it turned out – there were none of the usual good charitable works to point to as supporting a general aura of public-spiritedness, as is customary in such matters. Meanwhile, Britain’s success as an international banking hub helped drive Sterling up and manufacturing exporters out of business. Mr Brown tried to wriggle out of responsibility by suggesting that he wasn’t responsible for banking regulation under Britain’s tripartite system of financial regulation (between the Treasury, the FSA and the Bank of England). This is pretty damning, because this system was of his own design, and it was clear that overall responsibility for making sure the system was working lay with the Treasury. It couldn’t be anywhere else.

Then on taxes, Mr Brown engineered a switch from taxes on income, and Income Tax in particular, to an array of other taxes, like stamp duty, that turned out to be about milking financial bubbles. At the time, his reduction of the basic rate of income tax to 20% was lauded as a triumph. This proved a colossal misjudgement, as it has proved politically impossible to raise income taxes, even in supposed more left-leaning Scotland.

On top of this, a broader claim can be made. The world financial crisis was not some storm that happened somewhere else with unfortunate consequences for Britain. Britain was the world’s leading international centre of finance; Britain’s bankers were at the heart of it, Two of Britain’s big banks, RBS and HBoS, collapsed, not helped a Britain’s own reckless mortgage lending, which also affected smaller banks, like Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley. These banks had all adopted highly risky business models, whose main assumption was that global banking markets would be stable. Sitting on top of one of the most prestigious finance ministries in the world, and trumpeting his own reputation as a financial manager, Mr Brown and his acolytes can’t really escape the charge of incompetence for not appreciating these risks. And these risks were plan to some, including his Lib Dem shadow, Vince Cable, whose warnings were pooh-poohed.

Labourites are on stronger ground when they suggest that, once the crisis emerged, their government handled it well. It wasn’t pretty (amongst innocent victims of the government’s shoot-first approach were Icelandic banks and Britain’s own Lloyd’s bank), but largely stands up to scrutiny. Another argument is over whether the Tory/Lib Dem coalition that took power in 2010 was too tight with its austerity policies, compared to how Labour would have handled the same situation. Many independent commentators agree with at least the first part of that proposition, though I don’t.

So, I don’t think Labour were quite as innocent as they claim, even if much of the direct criticism is misplaced. But, in politics, such arguments actually count for little. A more important question is how the public perceives things. This is where Labour’s real problem lies. What the public sees is a classic hubris to nemesis story, which is one of the oldest storylines in humanity, and takes some rebutting. Labour’s problem is their boastfulness before the crisis. Labour appealed to voters because a Labour government meant “no more boom and bust”, unlike with the Tories. And then one of the biggest busts in history happened.

And there is trust issue here. Labour’s position is a bit like that of the Lib Dems over tuition fees. The Lib Dems vowed not to vote for an increase in student tuition fees before the election, and yet later that year they supported the trebling of fees. Many Lib Dems will give you a convincing intellectual explanation as to how this not nearly as bad as it sounds, and that anyway there was little they could do in coalition. But this cuts no ice with the public, because of the way the party presented their policies before the election.

Labour are onto an equally losing wicket if they try convincing the public that the economic crash of 2008/09 was not their responsibility. Ed Miliband, their leader at the last election, was quite right not to even try. Besides, the alternative argument that Labour were the hapless victim of world events hardly counters the public’s perception of the post-Brown leadership (Mr Miliband and his successor Jeremy Corbyn) of being nice but ineffectual. The usual advice for when you are in a whole is to stop digging. The idea that if the party had come out fighting, public perception would be swayed, is pure nonsense.

The only way forward is for Labour to acknowledge their responsibility, and put forward hard economic policies that show they are capable of taking tough decisions if in power. And that means they have to stop banging on about austerity and get tough with some of their own supporters. For now, though, there is no chance of that.