Anglo-Saxon economists were always sceptical. And so was much of the British establishment, though less so in the early days. But sponsors of the European dream were determined. And at first European Monetary Union defied the sceptics. But now the dreams are vanished and the only people defending the union seem to be those that have face to lose. Is it all over for the Euro?

It is Greece that seems to prove the scheme’s futility. The Greek government cannot repay its debts; its banking system depends on a bankrupt government for solvency and the European Central Bank (ECB) for liquidity. Greece cannot print its own money to inflate its way out of the hole. Instead European institutions and the IMF have to bail it out, and they are demanding conditions that add up to a loss of the Greek government’s sovereignty over its economic policy. Both sides blame the other, and the more the blame game goes on, the more trust and solidarity break down. The Euro is tearing the union apart, when it was supposed to bring Europe’s peoples together.

It doesn’t take hindsight to see what went wrong. Mostly the scheme’s weaknesses were pointed out at the start. Its supporters (who included me) just thought that this time it would be different.

Monetary policy is set at continental level, and yet there isn’t a great deal of economic integration. In order to adjust to local business cycles and local economic shocks, national governments have only a very limited set of tools. And the most important, fiscal policy, is constrained by the Stability & Growth Pact. This was instituted to try and prevent member governments becoming insolvent, a contingency that the zone had no process to deal with. This made it quite unlike a federal system, like the US, the only comparable monetary system that most knew. In the US there is a strong federal level of government, which draws substantial taxes from all parts of the union, and can make big fiscal transfers between the union’s members to compensate for the lack of monetary flexibility.

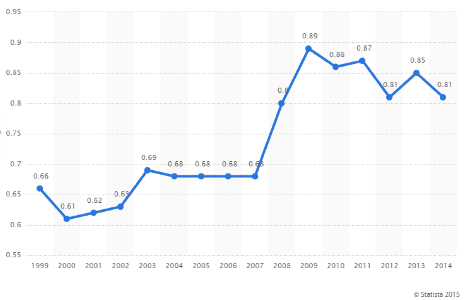

Funnily enough the problems with this set up did not play out in the way that most critics foresaw. They thought that different business cycles or local shocks in different parts of the union would be the big problem. This happened – especially when the central economies of Germany and France endured recession, while peripheral economies, such as Spain and Ireland fizzed. But these were not the main cause of the crisis that emerged following the global financial meltdown in 2008.

The first problem was that investors assumed that member governments could not go bust, and that if they got into difficulties somebody would bail them out. As a result, it became much easier for the peripheral governments to borrow, and this allowed them to run their economies with a looser hand than they should. This was most egregious in the case of Greece, who produced misleading economic statistics, which put their government into a completely unsustainable position. And when it was clear Greece could not repay its debts, the system had no set of processes with which to manage the crisis.

Perhaps Portugal and Italy were guilty of something similar without the fraud, though Italy has not needed a bailout. But the other bailout cases (Spain, Ireland, and Cyprus, though I am less confident that Cyprus follows quite the same narrative) the main problem was not government finances, but a reckless private sector that fuelled property bubbles. What added fuel to these bubbles was cross-border flows from elsewhere in the Euro area, and especially German banks. The Euro system had greatly facilitated such flows. When the bubble burst, it brought down the countries’ respective banks, and this in turn draw their governments down with them. Governments couldn’t let the banks go bust, since they controlled local payments systems and economic chaos would have resulted. Like Greece these countries then needed external support and bail-out.

The important point to make about this series of crises was that they were to great extent “endogenous” as economists like to say – they have to do with the way the system itself operated – and not exogenous – the external shocks and uncontrollable factors which most economists thought was the system’s weakness. That suggests that bad systems design was a large part of the problem – and that, in theory, could be fixed. Most suggest that it implies a fully federalised system, with a federal government, supported by federal taxes and federal debt. An alternative route would have two main elements: a national insolvency regime (a bit like US states, but not Puerto Rico, which is on the path to creating a US version of the Greek crisis); and banking reform to produce a more federalised banking system firewalled from member governments.

But either route would leave member governments facing a grim reality. The Euro offers a straitjacket for government finances, and not a liberation. In the fully federalised case, the scope of government responsibilities would be curtailed and handed over to a federal government. In the alternative governments would be heavily restricted by their ability to borrow in financial markets (which would do away with the need for the Stability & Growth Pact). This latter is, in fact, what many supporters of the Euro (including me) envisaged all along (though in my case I completely failed to grasp the difficulties of managing the banking system). It was rather a Thatcherite project. But others thought EMU would be a step along the path towards a federalised Europe. It was the unresolved conflict between these two visions of the Euro that got the system into its current mess.

And this conflict is still unresolved. But the federal vision is losing ground; there simply isn’t the political support for it. That doesn’t stop people in the European Commission from quietly pushing for it though. But those who aren’t convinced by the federal idea, aren’t convinced by the multi-state currency area alternative either. Why opt for a straitjacket? Wouldn’t it be more democratic and easier to say goodbye to monetary union altogether and let each country go its own way with its own currency?

And I don’t have the answer to that. One thing I will say is that the quality of economic commentary in the media is pretty dire. From this you would think that the advantages of having a floating currency make doing anything else foolish. But all Economics students are asked to do an essay on the pros and cons of floating currencies, and frankly it is not that obvious that either route is a winner. As a rule, the smaller and more open the economy, the more there is to be said for a fixed currency regime – which is why the Euro is popular with so many smaller EU members. Floating currencies reduce the effectiveness of fiscal policy, especially in such small and open economies. The rather loose fiscal policy of the Britain’s government in the 2000s caused the exchange rate to be too high, leading to a trade deficit and a hollowing out of British industry the country still have not recovered from. By contrast Germany has been able to maintain its industrial base within the Euro, albeit with some painful restructuring.

And a floating rate does not prevent banking bubbles. Iceland had one in parallel with Ireland, with its own currency. Recovering from the bust best no less painful for Iceland than for Ireland, though arguably not really any worse either.

But setting up a more secure banking system across the Euro area is no small thing, and its feasibility is an unknown. Against this, taking the Euro apart would be a huge undertaking, so there is there is much to say for trying to make it work on a rather less ambitious scope. Inertia is on the side of the Euro. But the starry-eyed enthusiam is gone